A BOOK REVIEW BY HIRANYA MUKHERJEE

As one sifts through the pages of Hélène Cardona’s Life in Suspension, one is welcomed at the doorway in the first section of the collection by a quote by Rainer Maria Rilke. The poet says: “I will have the gardeners come to me and recite many flowers, and in the small clay pots of their melodious names I will bring back some remnant of the hundred fragrances”. His voice sets the mood for what’s to come– a journey through the gardens of poesy, tended to by Cardona as her voice guides the reader through boughs of introspection, ravines of existential whispers, frontiers of galaxies, and the gentle spots of time colored by nostalgia and a longing for absent presences. A journey that upon its conclusion would leave the reader basking in the luminescence of the remnants of the hundred fragrances of Cardona’s poetic vision. Indeed, Rilke’s voice isn’t just limited to the opening section of the collection but reverberates through all the pages. In his Letters to a Young Poet, Rilke comments on his “ars poetica”, in his view poetry should blossom as a necessity of expression from within the poet. A necessity that is fueled by the stimuli of the outside world and the vast myriads of inner objects that stem from memory and dreams. Rilke’s poetic outlook puts special emphasis to a proximity with Nature, and an urge to traverse the experiences of one’s childhood to rediscover existence as being impinged with wonder, and a sense of fluidity that intermingles the immanent and the transcendent; words with silences, and flesh with God.

The collection begins with Cardona looking back at her childhood, specifically pulled back by the longing for the absent presence of her mother. She mentions: “The angel who smells of my childhood/ My mother, piano and oboe”. This sense of attachment and longing for her mother is a constant throughout her collection– the spectre of her mother does not haunt her though, instead acts as a guide for her. Her personal Beatrice, the mother guides the poet itinerant through the forests of introspection and valleys of reconciliation. In the “Peripatetic Gremlin”, the speaker mentions: “My life is a slide show/ projecting the same image/ again and again / a glimpse into a world full of light from behind bars,/ a world that escapes North and South/ as I stare at the Angel,/ transfixed,/ blinded by whiteness of time”. In this slide show of her life, time stands still, her life is suspended as she traverses through different moments of her past experience, prodded on by the guiding hand of her Angel, to discover what? Something beyond life, a sense of oneness between the individual and the cosmic. In “Ritual” the poetic voice utters: “I meet my friend the seagull on the rocks:/ mesmerized by ocean, we share this ritual./ I feel wind through my hair/ adore me like never before/…./How I disappear in azure eyes./ Words pulsate in my blood,/ I can read ad infinitum,…/Softness and power I cannot resist—/ hunter and hunted in one—”. In several of her other pieces this sense of oneness between the self and Nature– reconciling opposing elements such as North and South, hunter and hunted, self and other is reiterated. Cardona’s poetic vision is one that creates a symphony out of synergistically making eclectic voices speak with each other. She incorporates quotes ranging from Carl Sagan, speculating about the infinitude of the vastness of the universe to Rumi and Sri Aurobindo speculating about the futility of the limited capacity of words to the depth of the rhythms of existence, and the mysteries of dreams. As such, in “Time Remembered”, for example– the poet interrogates the self to gauge its fluid existential boundaries and explore a sense of oneness in all living beings. The voice asks the self: “Do you remember/ when you were wolf and I fawn/ when you were a fly caught in a web/ when you were a snake and I bear/ remember how we enchanted/ each other through centuries/ devoured one another/ became the other?/ Do you remember/ when you were eagle and I jaguar/ when we were two dolphins kissing/ or cougars in the rain/ so that now we can’t tell one/ from the other, our cells imbedded/ in a tapestry of shared lives?”. In another piece– “Eagle”, the self is expanded through an encounter with the “transcendent beyond”, as the poet mentions: “On the wall of time to come/ a window appears./ I open it, let angels in./ The vortex in his eye/ spins me out of myself./ Infinity held in blue iris/ closes around me, snatches/ me in Eagle form, reawakens/ old scars, swallows/ space and love, dissolves/ into the divine silence./ The universe cannot resist/ a poet like him”. The influence of Rilke is palpable here as well. In “The Rose-Window”, Rilke writes: “overpoweringly into its own great eye,—/ and that gaze, as if seized by a whirlpool’s/ circle, stays afloat for a little while/ and then sinks and knows itself no longer,/ when this eye, which only seems to rest/ opens and slams shut with a roar/ and tears it all the way inside the blood—:/ in the same way long ago the cathedrals’/ great rose windows would seize a heart/ from the darkness and tear it into God”.

Such yearnings towards the divine in Cardona’s poetic voice is reinforced by a proclivity towards enchantment and mysticism. In “My Mother Ceridwen”, the spectre of her mother, her angel, her guide, takes the form of the pagan Celtic goddess of rebirth, inspiration, and metamorphosis. The poet mentions: “the core of her at the edge of darkness/ in a magic cauldron always full—/ never exhausted—/ that brings her back in life,/ guarded by a golden serpent/ coiled in the shape of an egg,/ the world snake marshalling/ inner reserves”. The poet gazes in the magic cauldron of her own self, marshalling her imagination that is guided by the eye of divine Nature and finds the universe. The poet beckons the reader to join her in a journey, a journey with her life in suspension, yet prodded on by spasmodic movements of rediscovery where she interrogates the self to find multitudes within. One might find such reminiscences similar to the poetic vision of Walt Whitman in section 51 of his Song of Myself, as he addresses the reader: “Listener up there! what have you to confide to me?/ Look in my face while I snuff the sidle of evening,/ (Talk honestly, no one else hears you, and I stay only a minute longer.)/ Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”. Such contradictions in Cardona, or as mentioned before, reconciling opposing elements pave the way for the encounter with the divine, with the transcendent– in “Mind Games” the poetic self divides into its multitudes as the speaker mentions: “In the dream two of me/ catch up with each other, the first, curious, vulnerable mind/ pursues the other, flawless, invincible/ one, forever awed/ by its acrobatic, superhuman nature, swirling on the lee shores of the Moon”. In Life in Suspension, the reader is taken into such a journey of multitudes that one realises as one looks back where the journey started. The first section of the collection contains the titular poem, “Life in Suspension” where the poet paints varying tableaux from her life, a journey through some snapshots ranging from her existence in her mother’s womb to when she was fifteen years old. Her voice is embedded within two differing momentums: one of reaching out to the objects of longing from her past, towards particular moments of experience from her life to synthesise them; and the other, of reaching out towards the eternal, going from the particularities of the self to the infinitude of oneness in the cosmos. The mentioned tableaux of moments in the particularity of her life meld into the vastness of existence in general as she weaves a mystical tapestry using her verse in “Musica Eterna”: “Surprised by my lunar earth nature,/ inhabited by ancient forests,/ I molt into flying serpents,/ pelicans touching wings, magnets of expanded vistas, a crest crowned by doves,/ in its center the caduceus,/ entwined identity, magician’s score,/ water weeping out of hands”.

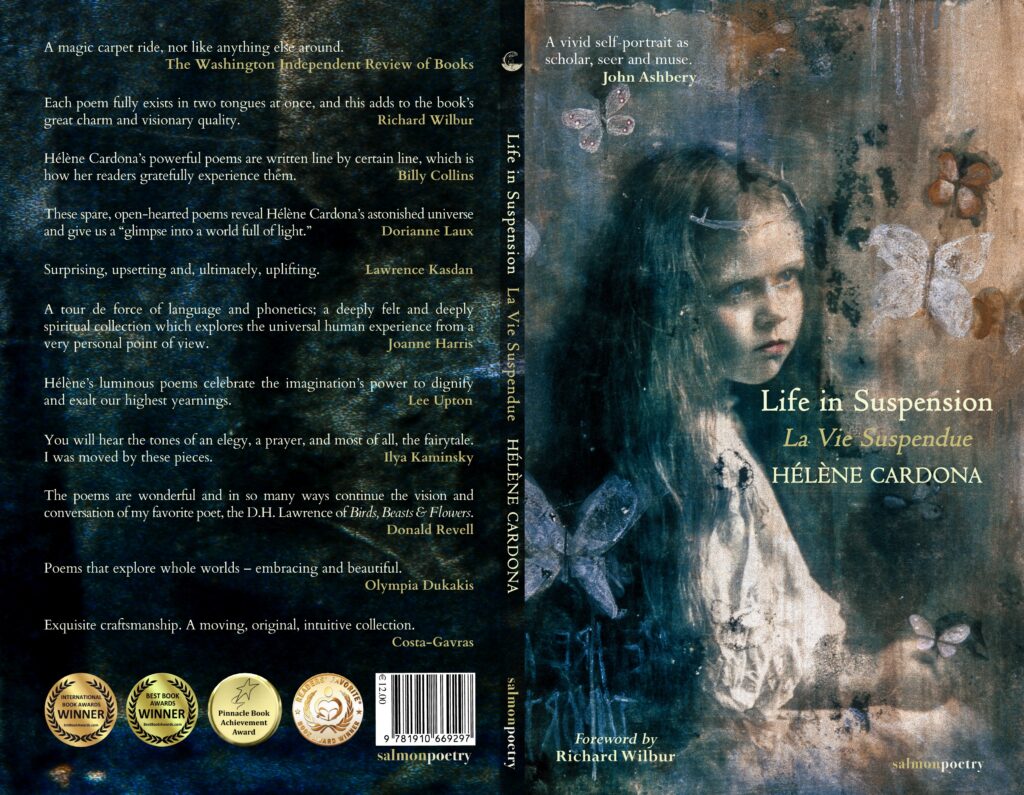

The poems in Life in Suspension are preceded by a foreword by Richard Wilbur who asserts that perhaps in the “many-languaged” mind of Cardona, the poems must have existed simultaneously in a bilingual form, both the French and the English versions co-existing in a mutually conversant manner. I would agree with the sentiment of Wilbur’s perspective, the poetic voice of Cardona is indeed possessed of multitudinous tongues that converse simultaneously in the languages of longing, of mourning, of discovery, of the mystical, of the divine. Her voice utters the utterable and reaches out for the unutterable, for the beyond that she captures through her rich imagery, and her dream-world meanderings. Her impetus to preserve and archive is simultaneously complemented with her desire for detachment, acceptance, and a yearning for new frontiers; impulses efficaciously captured in this poem that I end this essay with, “In the Nothingness”: “I count/ the years of my life,/ plucking daisy petals./ I count/ the losses of my life,/ blowing kisses in the air./ Perhaps if I cry my tears away/ for what will never be,/ I’ll still live/ what may become./ And if I give up/ what I never had,/ I’ll experience/ what I never dreamed”.

Bibliography

Cardona, Hélène. Life in Suspension. Salmon Poetry, 2016.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters to a Young Poet, translated by Stephen Mitchell. Vintage, 1986.

–. New Poems [1907], translated by Edward Snow. Macmillan, 2014.

Whitman, Walt. Song of Myself. University of Iowa Press, 2016.

Also, read The Second Taj Mahal by Nasera Sharma, translated from The Hindi by Ayushee Arora and Published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments