BOOK REVIEW BY URNA BOSE

THE “WHAT’S IN A NAME?” RULE APPLIES TO ALL.

ALL MINUS ONE, THAT IS.

URNA BOSE REVIEWS NABANITA SENGUPTA’S CHAMBAL REVISITED (An English Rendering of Suvendu Debnath’s Abar Chambal)

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Or so says William Shakespeare, the Bard of Avon in his play Romeo and Juliet to convey that a name is quite irrelevant and pretty much has no bearing, no significance, or throws any implicational light on the thing, place, person, or entity whose name it is, so to speak. Now, if one were to dig deeper into the sheer derivative power of this iconic line, what it means is that the nomenclature of a thing, place, being, or entity can be completely compartmentalized, if not cut off with a freshly burnished sword of pure Valyrian steel, from its functionality, purpose, value, or raison d’être.

As this reviewer ponders on this Shakespearean-esque idea, the reviewer senses a mischievous smile spreading across her face and she decides to cut Mr. William Shakespeare some genuine, compassionate slack, for Shakespeare’s rule surely cannot include the Chambal region, can it? Given how the very utterance of this word, ‘Chambal’ can make the bravest of hearts quake in their boots.

Yes, the name ‘Chambal’ can almost conjure up a veritable nightmare. With images of hardened dacoits riding towering stallions, looting and plundering without care, blood-curdling screams and horrific wails raging like an unquenchable forest fire, and afterwards, a quiet shroud of obeisance covering the destruction and the destroyed as the bitter bile of a fundamental law of the land seeps deeper into the blood, the bones, the personal and the collective memory – might is right ‘Chambal’.

The name ‘Chambal’ indeed carries a majestic magnetism about it, and it is because of this reviewer’s subliminal longing to understand the behind-the-scenes drama and the underpinning of what this name means that she started reading Chambal Revisited by Nabanita Sengupta – the English rendering of journalist and author Suvendu Debnath’s Abar Chambal.

Nabanita Sengupta almost intuitively answers the reader’s curiosity about her choice of translation material in her beautifully written Translator’s Note by stating, “Reading Suvendu Debnath’s Abar Chambal persuaded me to believe that this book needed to reach a larger community of readers. Hence the need to translate.” At a time when we are losing the nuances of our centuries-old regionalism and our regionality is sometimes viewed willy-nilly as a roadblock to our mainstream universality, it is the translator’s attention to follow each artery, bloodstream, vein, and nerve that will steer us back to what it truly takes to preserve our roots, our bones, the soil of our sustenance.

Academic, poet, and translator Nabanita Sengupta has not only refined the art of translation in this arduous labour of intense love, but she has pushed the envelope further. Sengupta approaches her translation with both commitment and focus and remains true to Suvendu Debnath’s portrayal of Chambal through “myriad lenses—looking at it through economic, geographical, social, communal, and gender perspectives. His gaze is that of a seeker, a person who tries to understand a place by interacting with its inhabitants”.

As this reviewer read Chambal Revisited, she instinctively felt that Sengupta deeply understands how language facilitation constitutes only a thin slice of the colossal pie of translation. Language, after all, is so much more than just a tool of communication or a medium of understanding each other. It is the catalogue of our cultural evolution, the distinct and not-so-distinct societal changes, why we eat the food we eat, what makes our attire the way it is, our belief systems undergoing tectonic shifts, our ways of seeing the world and our struggles to stand out or blend into the stream of the collective narrative.

Take a moment then, readers, and imagine the thousands and thousands of micro and macro cultures around the world all expressing the specifics, the individuality, and the cultural ethos of their being through their own language. Consequently, this becomes the job of the translator. To stay authentic to the spirit of the original text, and knowing how crucial this engagement is for generations to come and for all those who want to look back and piece together the legacy of a particular culture.

As Sengupta traverses the famous or rather the infamous “Chambal ke Beehed”, she takes the reader through a timeless conundrum – the psychological, emotional, socio-political, or economic catalysts that snowball into the making of an ordinary man or a woman into a “baghi” (dacoit/rebel). Stripping away the surface linearity, Sengupta does not shy away from holding up the ugly truths, unpacking the layers and the folds of the fabric of this complex, fascinating narrative.

At which point in the journey does a man or a woman decide to take up arms? At which crucial juncture does the individualistic battle catapult into a power struggle? How does “an eye for an eye” work at the ground level, where every day inaugurates a new version of the Darwinian “Survival of the Fittest”? Where the rugged, undulating terrains are as much a friend as a foe, depending on which side of the collateral damage the individual finds himself planted – sometimes as the king, sometimes as the kingmaker, or sometimes as just the pawn.

Sengupta does not just throw light just on caste politics alone but also illustrates how the gangs are mostly formed attune to “respect” and perpetuate caste hierarchies like the Ahirs, Rajputs, Gujjars, Kurmis, Malhars, Dalits, and Brahman gangs. Equally fascinating are the larger-than-life identities of people like Maan Singh, Malkhan Singh, Lala Ram, and Madho Singh, and their empires built on the bastions of valour, old-world charm, hero worship, and terror often couched in the velvet glove of romanticism.

The part that this reviewer savoured with utmost relish is the section on women baghis like Putli Bai, Neelam, Renu Yadav, Seema Parihar, and others. This section unflinchingly celebrates a cult within a cult. A smaller band of women compelled by the hands of fate and vicissitudes, fearlessly exploring the boundaries of what it takes to be feared in a land where “Fear” is the only God of things small and big. While Sengupta does dwell on gender politics and marginalization, this reviewer would have preferred to read a much more in-depth account of these women and the sheer dynamics of power play between the reigning gods and goddesses of a land that reveres bloodshed.

Sengupta does a brilliant job of translating the up, close,and personal portrayal of Suvendu Debnath’s critical approach and journalistic rigour of the veritable reign of terror in the Chambal basin. Though if one must turn a critical eye at this book in a bird’s eye, holistic way, one must admit at times that it felt a few scattered strands here and there which did not quite add up for to the cohesiveness of the overarching narrative and in what it wants the reader to mull upon. However, truth be told, given the sheer complexity, personal detailing, and depth, perhaps that is understandable too in hindsight.

What makes Chambal Revisited riveting and unputdownable is its close-to-the-bone honesty and its ability to hold a mirror to the reality, the counter-reality, and the tightrope walk that these two entail. That there is a lot more than what meets the eye, like lack of administrative support or the abysmal levels of poverty and rampant exploitation. As one gets drawn into the intricacies of what it takes to survive and thrive in the ravines, the reader will perhaps somewhere along the line drop their own inner, constrictive value judgement of the good, the bad, the ugly, and the glorious. Who are we to decide that? Who are we to hold on to our narrow, restrictive viewpoints? Who knows what we would have done, if we had to walk a mile in the shoes of those baghis?

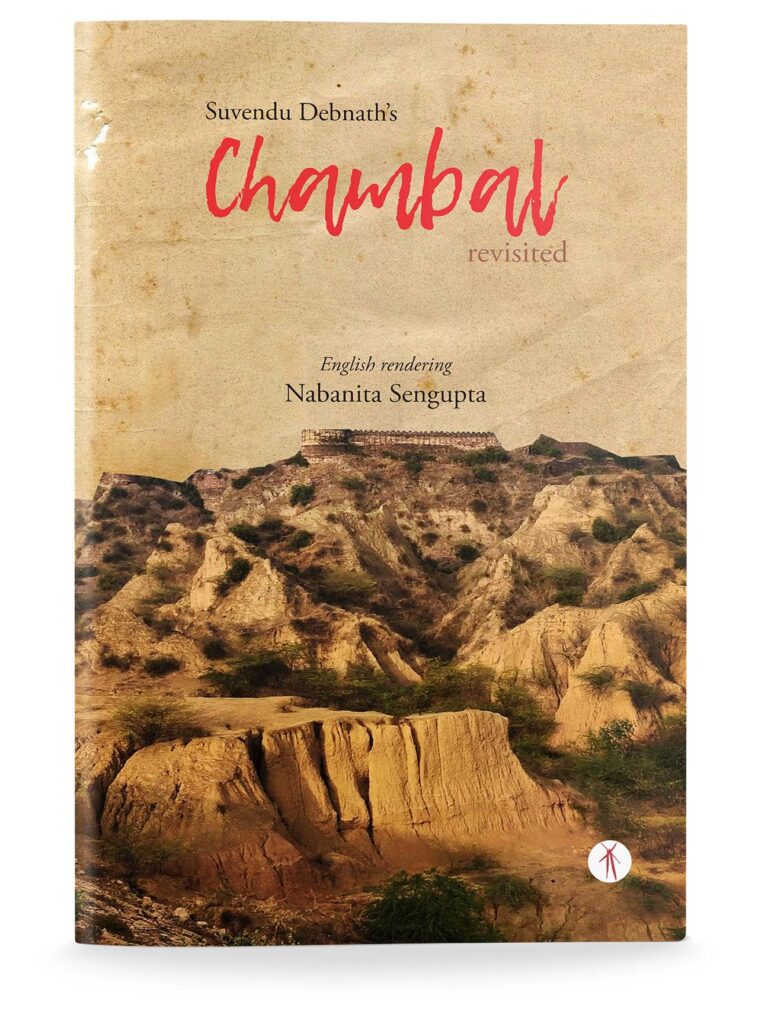

Sengupta’s translation of Debnath’s work, this reviewer believes brings the reader to that place – that critical boiling point of a larger universal realization somewhere along the journey of reading Chambal Revisited. That is the purpose of discerning, in the flesh, first hand, contemporary non-fiction. Published by the New Delhi-based Hawakal Publishers, with its intriguing cover design by author-publisher Bitan Chakraborty, Chambal Revisited doubles up as a collector’s item, a serious traveller’s compendium, a sociologist’s microscopic understanding of the Chambal region, and the starting point for newer discourses on the Chambal’s empirical, socio-cultural and gender issues.

Finally, any work of translation is the means of accessing stories, anecdotes, and experiences beyond narrow borders, fences and the barricades of conditioning. Engaging the senses and aiding one to fully comprehend the cultural exports of microcosms and worlds beyond one’s own self-imposed myopia, thereby addressing a rather debilitating combination of the complacency of what is “own” and the fear of the “other”. So, whether it is Anna Politkovskaya’s Putin’s Russia or Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince, it is incredibly important that we have access to cultures and societies that are beyond one’s own. This is exactly why, Nabanita’s Chambal Revisited is also a history-making tour de force in the universe of seriously invested, potent, and thought-provoking contemporary translations.

Also, read “Via the Mouth and in Writing” by Claudine Helft, translated from French by Patrick Williamson and published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

Urna Bose is an award-winning advertising professional, writer, poet, editor, and reviewer. Her poetry has gone viral, globally. She won ‘The Enchanting Editor Award, 2019’, from the Telangana Poetry Forum, the ‘Women Empowered – Scintillating Creative Impactful – Feminine Power Inspiration Award, 2020’ and the prestigious Nissim International Prize for Poetry, 2021. As the Deputy Editor for Different Truths, she also devotes her time to the ‘Poet 2 Poet’ column. Bose has been the brainchild behind a vast body of iconic advertising campaigns and brand work. Her campaigns have won both Indian and global creativity awards, and some are even industry case studies.

Urna Bose is an award-winning advertising professional, writer, poet, editor, and reviewer. Her poetry has gone viral, globally. She won ‘The Enchanting Editor Award, 2019’, from the Telangana Poetry Forum, the ‘Women Empowered – Scintillating Creative Impactful – Feminine Power Inspiration Award, 2020’ and the prestigious Nissim International Prize for Poetry, 2021. As the Deputy Editor for Different Truths, she also devotes her time to the ‘Poet 2 Poet’ column. Bose has been the brainchild behind a vast body of iconic advertising campaigns and brand work. Her campaigns have won both Indian and global creativity awards, and some are even industry case studies.

0 Comments