TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN BY BRENDA PORSTER

Doti d’ingegno aggiungi alla bellezza;

Essa è fragile dono: passa il tempo;

Col tempo ella trapassa, deperisce,

Del suo stesso durare si consuma.

Ovidio, L’arte d’amare, II, vv. 113-114

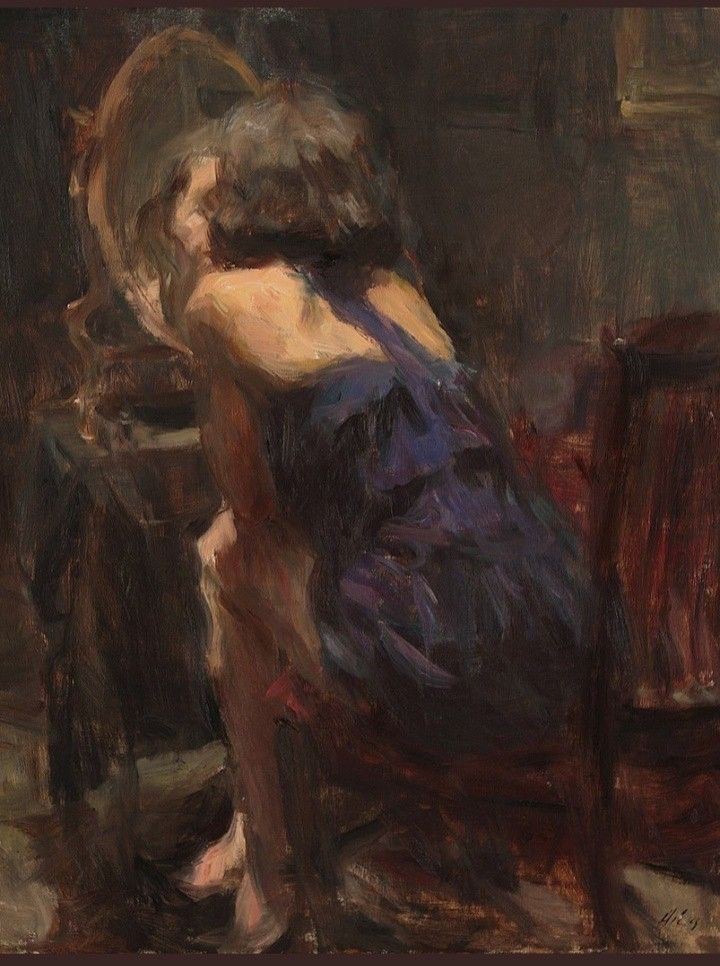

Sleeping beauty

My mother has always been beautiful — beauty was her hallmark, her serene certainty, her fatality. Mantled in an unfailing loveliness that never cost her any effort, a natural loveliness reconfirmed at every age — beautiful pale-skinned little girl with red ringlets, Botticellian maiden, soft-profiled woman, still beautiful even with her green eyes imprisoned by wrinkles — in the end, she wasn’t able to defend herself or develop faculties better suited for survival. Perhaps she was led to believe that the world would reserve a special happiness for her, in recognition of this rare property of hers, pure beauty.

And she, timid beneath the show of beauty, never considered it a talent to exploit, an arm for asserting herself, but simply the quality that summed her up, that fully expressed her. Hers was a naïve beauty, because it was without artifice, but above all because it was the source of an illusion that for a long time led her astray and in the end betrayed her: the illusion that beauty was her capital, her specialty, the source of every gift that life might offer her. Born so beautiful, she didn’t have to do anything to make her gift grow except to continue being exactly what she was, spontaneously and without cosmetics. Perhaps this is why my mother has hidden deep inside a doubt about her worth, about the place she deserves in the world. She had done nothing to be beautiful except to be born with that copper sheen in her hair, those green eyes and that delicately freckled fair skin. Other women, less fortunate, had to use their wits to show off their strong points, strive to be elegant or studious, ambitious and attractive. She remained a prisoner of a marvelous natural enchantment. She, the Sleeping Beauty. For me, daughter of the Sleeping Beauty, beauty has represented an enigma, an oracle to consult, a cruel divinity to whom all ingenuity must be sacrificed. My beauty and that of others, the beauty of women, almost devoured me.

She seemed delicately proud of being above the usual wiles of her sex, above every conquest the power of beauty confers on its followers. On my part, feminine beauty soon appeared to me like the quicksand in a treacherous territory where it was essential to fight and often to feign, to engage in bloody battles while pretending to know nothing about them. Above all, to pretend to believe that a woman’s beauty did not have to pay its dues, that it was welcomed and contemplated as a glorious mystery by all, men and women alike.

Far better, then, to take refuge in challenges that didn’t show off the body as treasure, but were created by a more deeply hidden power. A minus rather than a plus. A subtle strategy to escape the vulnerability of the flesh in favor of the dry, neutral resistance of the bone. An ascetic delirium of omnipotence to protect me from the intrinsic risk of a beautiful female body: the risk of erasing every other quality, of turning into a lovely woman, and nothing more.

Nothing more? and everything else, all the cost, the fear and the burden, all the complicated framework that served to exhibit beauty and protect you from its risks, the seesawing combination of bit parts and prohibitions, of reserve and admiration and envy, of comparisons, conquests and capitulations… my mother had never taught it to me, that hypocritical game that obliged women to make themselves ever more beautiful at the same time as they pretended not to know they were, so as to avoid immediately evoking diabolical condescension and capitulations. And she herself seemed to lack this knowledge, or to know only fragments that couldn’t resist the impact of my curiosity, my first explorations of the link between beauty and seduction. At those junctures she looked so troubled that she seemed to be taken unawares. Was she naïve, or so frightened that she had erased in herself the first symptoms of the turbulence that had overwhelmed me?

One day many years ago, emaciated and sharp-boned, I thought I was obliged to make amends in the name of something that was overtaking me or, better, preceding me, and in any case dominating me. A fierce divinity gripped my neck, keeping me from swallowing and demanding a tribute in pounds of flesh. The witch wanted to get even with me, maybe because my mother had neglected to sacrifice on the altar of Beauty. Victim of the spell that kept her suspended in a dazzling adolescence, my mother had refused to look beyond the mirror. In retaliation, for years the mirror was the instrument I used consciously and methodically to measure my power of destruction, until the prison of flesh that kept me from growing collapsed.

Beyond the mirror there was a dark world where the origins of deception were hidden. I was searching for a steady light that could illuminate my path to the discovery of the Sleeping Beauty’s crystal prison and shatter every glass, every reflection.

We can’t pretend to live comfortably in beauty, we women. Each of us could tell a story of blood and of delicateness, of flesh afraid of being crumpled, of envy, mistaken calculations, uncertain victories. We are fragile to this day, terrified by beauty and its opposite, obsessed by its logic and loss and by the all-too-frequent experience of our incapacity to truly enjoy it …

The magazines are still chock full of exorcisms and spells guaranteed for all pockets and ages. Even if we’d never buy the costliest creams, would not (ever? for now? who knows?) lift our faces or swell our tits, we read these fantasies for their calming effect: for a few pages we live in a gratifying world where every defect is reduced or erased, where abstract perfection strews its promises and introduces us to the uniform hoax of the consumption of prêt-a-porter beauty.

In this story, which unceasingly mixes concrete bodies and imaginings, we thought that men were the starting point of a millenary narration that had to be contested. We hoped that by forming new pacts among women we would in the end undo constraints and corsets forever, and for all of us. But men stop at the threshold of the demonstration — or contestation — of our beauty, involved with us in a performance of appearances and misunderstandings and sidelong glances, one that can absorb us all our life and keep us from encountering our woman’s body free from the constraints of measurement. Beyond the threshold of that game of glances, beyond the realm where we ask the mirror for impossible assurance, drives that make the blood freeze and boil come into play. If we don’t let ourselves be sidetracked by that impossible stupid competition (who is the most beautiful in the realm?) we can discover more fatal fears and attractions, the cravings in which women’s power games are expressed.

But what monsters meet if Beauty no longer waits for a prince to awaken her, if in the mirror we discover we are all a bit Wicked Queen and a bit Snow White? Is a mother who envies her daughter only a step-mother and blood-thirsty? must a daughter pretend to be the sister of asexual dwarfs to avoid being an insidious competitor?

The Artemis Girl

When I was still a child I chose Artemis as the most seductive of the goddesses. A slender young woman, quick-stepping, her lunar fascination always veiled by the foliage of the forests she could disappear into. I was irritated by the extravagant Aphrodite, ancestress of and model for capricious and destructive females like Helen of Troy or the femmes fatales of literature and cinema who lorded it over others, sowing the seeds of ruin. Artemis the wild seemed to me more frightened than dangerous; she followed her instincts rather than the complicated arts of human seduction and promised more freedom of movement than the beauties fossilized in their divine narcissism.

The dark sides of her myth, tales of admirers torn to pieces by dogs and punished for violating her only by looking, disturbed and irritated me like a useless addition, a sanguinary exaggeration: if her most extraordinary power was to disappear into the wilderness, if she was so free that she could shun admiration and become even more solitary, why did she need to vent her cruelty on someone who for a short time wrapped her in his desire, in his furtive admiration?

Yet I would have done better back then to explore that blend of admiration and profanation, because it involved me, it involved us, and I didn’t understand that at the time. I write about it today as if I were fishing up a piece of wreckage: the sense of modesty that seemed a useless, suffocating implement, like our grandmothers’ corsets.

A shameless generation, is that what we adolescents of the mid-sixties were? What I remember, instead, is the difficult gap between the collective model and an intimate, very private sense, not confessed even among friends and companions. Almost as though the liberating and libertine imperative that we ourselves were spreading, happy as we were to bury patriarchal prohibitions and feminine demons, ignored our constant wavering between the courage of contestation and inner qualms. It wasn’t easy to lose our virginity, even when the desire circulating between males and females opened spaces and bodies, and allowed us to do it … or obliged us to?

That was my doubt back then, a doubt hidden so deep that it couldn’t reach consciousness or feeling, a doubt blocked in the body’s depths — occupied as we all were, males and females, by the desire to fall in love, to “go together” as we said, imagining “together” as a happy fusion that would give us the energy to grow, explore and pleasure one another. A conflicted body, bursting into a more highly sexed attractiveness than the bourgeois girls who came before us, but all the same a body enclosing delicate, mysterious qualities that risked being crumpled, like wings too tender and inexpert to fly.

Beauty complicated the distance between males and females: were the most attractive of the tribe trophies to be paraded about, or companions on an equal basis? And those metropolitan nymphs in mini-skirts with mimosa in their hair, did they have the right to try and transform the world, or were they only supposed to let themselves be flaunted?

We were in a hurry to get rid of our naiveté. Every obstacle had to be overcome, and modesty — which not many years before had been the chief virtue and dowry of young girls in full flower — became a ridiculous word for bigots. We were hungry for free bodies. Nor was it by chance that our newly ripe sexual liberation coincided with the explosion of our adolescent bodies, so that the mini-skirt became the symbol of a collective desire for amorous merry-go-rounds, mass embracing that could be vulgar, happily vulgar and amoral, as boys and girls know how to be. But there was then — as now — the frightened and wild side of the adolescent in front of her beautiful, growing body. There were invisible, or perhaps subterranean, desires that could find no expression in the challenge to morality that had superficially freed us from patriarchal prohibitions.

That inner body of adolescent girls, the body secretly mirrored and anxiously measured and examined, which each one of us had to defend on her own precisely because collective and family protections had been shattered, was violently turned outwards to become a body on show. Thinking back on those years, I realize that I resorted to unconscious stratagems to dim that daily exhibition. Though I didn’t refuse it, I didn’t really feel completely ready: I wore hot-pants even at school, but I had my hair cropped short by a barber, and I can still remember the moment when I sat in front of his mirror, half of my face caressed by long hair and the other already laid bare by a masculine cut. Proud then of what I felt was only a gesture deriding stereotypes — I was virtually bald next to my long-haired boyfriend — I now discover the paradox of a provocation that unconsciously aimed at hiding myself a little, at going back to neutrality, veiling a femininity I couldn’t yet master.

In the Letter to Corinthians, St. Paul writes that «a woman’s long hair is her glory»; for me that glory was blinding, like a spotlight pointed at me stealing the shadows I needed. I felt pressured by the burden of beauty, expropriated of a quality I needed to assimilate gradually in order to draw strength and happiness from it. On the contrary, I wielded it in public like an inexpert sapper in danger of being blown to smithereens. I wound up concentrating on ways to defuse it, looking for the shadowy sides of roads and for shelters. Tricky, dangerous stratagems these were, based on subtraction and flight, though it appeared that my growth proceeded side by side with the others, all of us trying to protect and help each other get through these difficult transitions.

Boosted by a collective show that gave us constant support, we explored the meanders of sexual availability interlaced with seduction. Friends and partners shared knowledge of contraception and helped each other face the fear of abortion. Males and females of the same age confided in each other, teaching and gifting practices of sex and love. But we weren’t able to share the fears rooted in forms of modest reserve hurriedly labeled as reactionary error. And in the end they dispelled the enchantment, isolating us from each other. Until the time when, slightly more mature and bruised, certainly tougher than our tender high-school bodies, we could finally disclose those fears to each other in self-awareness, and find ourselves united, perplexed, more sincere, closer.

Under the skin of the she-bear

In the museum of the Turkish city Selçuk, next to the ruins of Ephesus, there is a room where the sacredness of three statues of Artemis intersects. The smallest, later and more refined In the working of its brilliant white marble, seems to be put to one side, while the two more important ones face one another, calm and potent. The largest, set in a large illuminated niche, is the oldest. Made of stone, ochre-colored rather than white, her facial features are almost entirely worn away. She wears a crown with layers of towers, and a stiff dress shaped like a sarcophagus housing a body so large and compact that the feet cannot be seen. The upper part of the bust is decorated with necklaces and rows of acorns, with an ample ruff showing the signs of the Zodiac, the same motif that covers the shoulders and throatlatch of the other two statues. On the bodies of all three statues various orders of animals sacred to Artemis alternate — bees, bulls, lions, deer, griffons and sphinxes; while in the upper half of this impressive figure the sequence of beasts dear to the goddess is overhung by a multitude of breasts like bunches of grapes. Archaeologists no longer think they are breasts, but rather the testicles of priests who emasculated themselves in rites of submission to the Goddess.

In the great hall, the triangulation of the three statues almost identical in their decorative elements, like variations on the theme of Artemis’ divine attributes and her ties with the natural world, produce an almost unbearable effect of sacredness. Eyes full of tears, I stand before the largest because undoubtedly she, the first-born, is the one to kneel to. I’m amazed by the transformation of my girlish Artemis: here there are no statues that help me envision her in the short simple tunic she wears to avoid branches, with bare arms that make it easier to carry bow and arrows. That young woman, as agile as her dogs, shy as the deer whose horns she grips, now stands over me transformed into the Lady of Beasts, patron saint of Amazons and nymphs, direct descendent of the Anatolian Great Mother. She presides over one of the greatest temples of the ancient world, numbered among the Seven Wonders, and her cult is found everywhere, enduring and multiform. She is the patron saint of virgins and women in labor, mistress of the hunt and protector of wild beasts, lunar goddess and sovereign of the stars in the shape of the Great Bear. The she-bear, the animal under her protection, appears in myths where humans are punished for harming her, and a she-bear also appears in the myth of Kallisto, “the most beautiful” of the nymphs, made pregnant by Zeus and changed into a bear by the Virgin Goddess, angered by her betrayal.

Before the age of marriage many Athenian girls passed a period of time dedicated to the cult of Artemis. They were brought in groups and lived in the sanctuary of the goddess at Brauron, an Attic temple about twenty kilometers from the Artemis Brauronia sanctuary on the Acropolis in Athens. Every four years a springtime procession led the adolescent girls from Athens to the sacred area of Brauron, where they lived for a time under the protection of the Goddess and took the name of “arktoi”, little she-bears. The cubs wore saffron-colored tunics died with crocuses, a color the Greeks associated with menstrual blood. They performed sacred dances, sacrifices and ritual races; it is thought that in the final race they were chased by a “bear” before emerging from the rite of passage tamed and purified of their wild nature.

What bear skin could have protected my no longer childish body until it was ready to show itself? What rites of passage could have helped me to recognize my instincts, and above all to overcome my reluctance to accept the consequences that beauty was causing in my life? I don’t remember any. Rather, I remember the happiness of the times when my body wasn’t an encumbrance, but rather a vehicle of pleasure, dancing, caresses, long walks, summer. Or else it was an instrument for going further, towards the ecstasies of a metropolitan afternoon. It was my body along with others, inexpert and vibrant like mine, males and females attracted by our differences but equally tempted by the androgynous mixings and crossovers favored by the fashion of flowers and lace sported by the boys and androgynous caps and military-style jackets worn by the girls.

A beauty made of miscellany was born, spurious if compared to the canonical purity or the satanic beauties of the years before the war. It was a messy beauty, as if we were still little boys and girls wearing costumes, children dressed up in clothes borrowed from exotic lands. And in fact at fourteen adult femininity seemed farther away than a lunar landscape, too uncomfortable to contain all the energy I felt. The garter belt cut into the hips, stockings drooped, body hair grew, it was hard to walk on high heels and even harder to run. Very soon after we found more comfortable ways to dress, with breasts free under our T-shirts, wide skirts, low-heeled shoes or even mules, clogs and sandals, our hair loose, uncombed, braided, unraveled, our faces not made-up but painted, jewelry transformed from signs of distinction to ornaments of tribal belonging. To the adults those teenage bodies seemed irrepressible, while we carried them around without being totally aware of the erotic potential we’d taken the lid off of.

The removal of the electric charge — both risk and richness, to be handled with care – that lay behind false modesty was an old expedient that had become useless, or maybe good for cautious approaches, like steps in a parlor dance, slow as Sunday strolls complete with parents and chaperon. We inaugurated the era of self-exhibition in discos, we were the mothers of the teenage podium dancers and the grandmothers of today’s little girls with make-up. We tore off the old skin of modesty, uncombed the lacquered fixity of hairdos in vogue only a few years before, shed garters, girdles and bras, exhibited ourselves with cheeky innocence — our bodies, ourselves.

We tried to ignore the traditional measurements of beauty: the wasp waist, abundant curves, ideal weight, the obsessive control that women’s glances held over other women from when they were girls through to old age. Janis Joplin wasn’t ugly for us, that was no longer our criterion for recognizing the potent charge of seduction that had us in its grip. She represented us, she had inaugurated a breed of “material girls” that would arrive as far as Madonna in the refusal of the ideal of Beautiful-and-Good, and of its repercussion, the depression of Baby Blue.

Spreading collective narcissism among women, even before understanding it theoretically we’d experienced beauty as a relationship, a form of power between the sexes, a system of amplification of desire in concrete bodies, ideal projections and ghosts inherited from one generation to the next. Through a powerful collective exorcism we had dispelled the parade of obsessions and insecurities that had accompanied every woman, whether beautiful or ugly. In feminism, a group of women produced an alchemy of mutual seduction that transformed envy into admiration, though it left behind a small residue that couldn’t be assimilated, a minimal toxic element that at the time we could ignore.

Other women’s eyes from pitiless became loving, teaching each of us to accept herself. The singular appearance found its pacification, along with everyone else’s, in a welcoming collective body — we were all sisters who could see every one of us as beautiful and desirable. Having hidden or re-educated our step-sisters and mothers, we told ourselves a new fairy tale.

We were trying to be independent of the measurements that had up to then certified the correspondence of real female bodies to unreachable ideal criteria, not to be influenced by the more democratic and accessible measurements fixed from time to time, from season to season, by fashion and its fetishes. To become independent of men, to whom we no longer acknowledged the right to classify and choose us. But after a few years the ingredients of the our young-witch alchemies lost much of their effectiveness … a residue floated up out of our cauldrons, a bile-stained morsel, bitter and unfit for our Rose-Red mouths. The covetous Wicked Queen reappeared, put on a pair of 12-inch spikes and a tight-fitting suit and came onto the stage. Her mission: to make way for the excessive — higher heels, bigger tits, more painting.

Paradoxes

Female beauty is marked by paradox. At the very time when its adolescent explosion manifests itself most provocatively – when the nerve of youth is most explicit, when surprise at the swelling body is still unstained by worry and heavy legs don’t rule out a short skirt or childhood fat low-slung pants — already in this Lolita exhibition we can find the pink-gold bud of fragility. An anxiety undermines the joy, a weakness — still buried below the freshness of the skin — where fear will soon take root.

How much, and what, is allowed to an adolescent’s beauty? How free will she be to dress and undress, to dress up and experiment? What will she have to defend, a desirable body or an uncertain, gendered soul that is becoming a woman but does not want to pay the price? And who must she protect herself from, who are the men and women watching her and what do they see when they study, admire, measure and control her beauty?

I wonder if every woman feels her own fragility so extremely, or does it happen only to some to find themselves vulnerable just where the world judges them to be stronger, where ostentation triumphs and aesthetics enjoys its little victory?

There comes an age when a pretty little girl finds herself in danger, just as she realizes that she has become dangerous. Frightened, she touches her body and the ground, which are quickly becoming unrecognizable. She has two paths before her and often she travels both, in turn, possessed by a secret fear that will never leave her, even in old age. On the one hand she will choose to arm herself, sharpening all the natural and artificial tools that have shielded beauty over the millennia, even when they seemed to strip it naked. Following the other path, she will disarm her body’s desire to the point of flattening it into absence, or else swelling it into anesthesia of the flesh: the voluptuous body of a girl with few feathers but already some bruises, or a slender boy’s body that takes refuge in neutrality because she doesn’t want to fight a losing war.

A woman’s beauty can remain a paradoxical experience all her life. Though it is the feature that marks her and makes her stand out, she can find it hard to experience as her own. Perhaps because it is such an oversized burden, so heavy to carry, we divide it into just so many body parts and offer it to others to consume and give back to us in more filtered and domesticated forms.

Women in the road

Two films that came out between 2006 and 2007 depicted the youth of the sixties, inviting us today to look back to the beauty/sexuality link that characterized us then — “Factory Girl” by George Hickenlooper and “Across the Universe” by Julie Taymor.

In the former, the slender, elegant vulnerability of Edie Sedgwick, American heiress who in a flash became the muse of New York Pop culture, is the irresistible prey of the misogyny of the rich-and-famous, from her incestuous father to Andy Warhol, in league with other, more transient stars of the Factory. In the whole film there is not a single moment when Siena Miller-Edie is not represented as a metropolitan fawn among the wild beasts of the drawing-room and the loft, a victim on the altar of self-centeredness, able to destroy and let herself be destroyed, but not to stop reciting a part.

In Julie Taymor’s film, instead, the girls-in-love who gallop over a universe backed by a Beatles sound track know how to run risks without inevitably immolating themselves. Each one finds the way to develop her charms, but Sexy Sadie, played by Dana Fuchs, triumphs over all the others as the volcanic interpreter of a freedom that won’t put up with shutting feminine beauty into any sort of pre-packaged container, not even the pop can of Campbell’s Soup. The triumph of her savage attraction occurs when she sings the throbbing Why Don’t We Do It in the Road on a nightclub stage — no one will be watching, why don’t we do it in the road? It takes her only two stanzas to capture the erotic charge of a happily outrageous sexuality, modulated in those few notes by her hoarse voice and by a body decorated with baubles, half-covered by a mane of red curls. Sadie embodies one of the many paradoxes of those years, when liberating beauty also meant burning some of its props, allowing body hair and flowing manes to go untamed and underscoring eroticism by blurring the stereotypes of male and female gender.

Does Sexy Sadie — a sadist because she’s a beautiful woman who doesn’t buy into traditional seduction, a woman who “shows it so that everyone can see it” — represent the wicked woman mocking everyone else? Are we still caught in the spirals of the same old story, where the pure young woman goes to her death because sex corrupts her, while the vamp castrates the men who adore her? Or has the game become more complicated in our world where desire is sealed with silicon, self-glued?

Thirty or forty years ago Edie and Sadie were two faces of the selfsame offering that had to be paid to cross over to new shores. Two faces of the coin we earned while liberating ourselves from our mothers’ sexual self-pity, those poor, beautiful post-war mothers of ours. But who did that emancipating coin come from if not from those very mothers, who were for the first time trying to invest us, their healthy, bright, well-educated daughters, with their own desire for personal achievement?

Their messages may have often been unconscious and were always contradictory — how could we “be proper” if we were to take part in competitions in school, sports, politics and sex, along with the boys? how . much time could we waste “making ourselves beautiful” if the important thing was to be clever? But they influenced us down in the depths of our unconscious minds and growing bodies. Our “poor” mothers invested us with their will to power, which up to then had been directed exclusively at their sons and sublimated in the myth of the home. Our dowries could, or better should, be spent out in the wide world, our beauty, though still greedily protected, could be exhibited and exchanged for hard male power and not only adored under the veil of Maternity.

If we were able to create ties among women that bonded us to each other under the hallmark of abundance, letting this golden light filter down to the body to make us all desirable, it was because our mothers had invested us with their own desire for affirmation and admiration, and we, their indomitable daughters, felt ourselves ready to join battle. In their name, too, even though not exactly with their banners, because instead of our mothers’ symbols ours carried new figures and words that proclaimed our difference from them. In the streets we waved the symbol of our sexed bodies, the sign of the sex they’d taught us to keep hidden, to use parsimoniously and, if necessary, to disown.

And so it wasn’t an easy gift to accept, that hesitant maternal investiture, like the magic goldfish in the fairy tale that transforms a poor fisherman into an ungainly Croesus. The admiring looks of our mothers represented a two-sided sword, holding ambiguous promises. We had the right to go forward thanks to our intellectual gifts, but would we still be chosen mainly for our attractiveness? or for our merits? or for our wrongdoing? The two qualities continually turned into one another, morals belied what the market affirmed, the new rules of scholastic and professional competition were replacing the canonical measurements. Miss Italia seemed a pathetic competition for dinosaurs, but we hadn’t foreseen how tough the skin of the Beautiful Beast really was … it might be as light as tissue, but it turned out to be almost indestructible.

But following the most banal cliché of femininity the challenge was arriving in the form of sacrifice, in the guise of privation. Like a silent contagion it lay hidden at the heart of the empire of contemporary beauty, in the world of Fashion, but its origins were certainly not on the catwalk, where they simply found its caricature, its orgiastic cult of fame and famine. Anorexia had already begun to appear like a crevice in the new simulacra of feminine beauty in the decade of the sixties and in only a few decades it was to become an epidemic.

Woman is a ponder(ous)ing being

Exhibiting an ossified body, its gaunt denial of completeness and maturity, the punishment of all carnal joys deriving from fullness and softness, an obsession with size that is the exact opposite of silicon swelling, the deformation of instincts sacrificed in the name of a vampire-like divinity … to what purpose? Less weight, more power — the obsessive mantra of the anorexic. The less I want something, the more I desire everything; the less I make my presence count, the more my absence will speak for me. The uglier I become, the more I please myself … what perversion governs the change from the good teenage girl to the anorexic? What deadly misunderstanding deforms the message we are sending, from mothers to daughters, from woman to woman? Because I am convinced that even in the perverse tightening of the knot of beauty represented by anorexia, the critical discourse takes place among women. It contains both the progress and the involution of the issues of male and female gender that women have been facing for fifty years in our saturated Western world.

We are all involved in the dilemmas of saturation, which doesn’t mean wealth at all, but rather “too-full”, the offer that precedes desire and tries to channel it into consumption. Even when poverty has crept in, when it spreads unexpectedly, bringing down the scaffolding of the circus tent, the temptation offered is a collection of cheap trinkets, the much-and-bad. The ghosts of privation are dispelled with Chinese smoke, and the Amazon is re-embodied as a warlike virtual salesgirl invading the world.

An anorexic tries first of all not to be consumed, and never to consume everything that is set down in front of her. Even when she has recovered and is once again able to grow in her body, to accept the cycle of production and destruction that governs the economies of bodies and of goods, she will always be tempted to leave something on her plate: not to be completely full will always be her temptation. Dissatisfaction will seem the essential mainspring of her existence.

Disobliging in her depths, even stubbornly hostile to gratification, though in principle so docile… it is not by chance that the anorexic teenager grows wild at the very age when she comes close to the risk of being tamed. She rebels with absurd self-destructiveness, to the astonishment of those who always thought she was the most obedient of daughters, the nicest, the most in line with their expectations. And this disappointment erodes the heart of the mother, who can no longer put anything on the table to tempt this monster of a daughter, or measure her harmonious growth. Rather than growth there is reversal: Gretel’s finger becomes thinner, flatness takes over where fullness was starting to bloom.

Yet the anorexic is extremely fragile, and only the folly that turns family ties into knots gives her the illusion that her ugly, ruined body is an instrument of self-defense or even a weapon of offense. As a matter of fact, the loss of her body disarms her and the only outcome of this proximity to death is defeat. But by the time she realizes this it’s often too late.

Beyond the looking glass

What unites the two opposites — the body made ugly by fasting and the beautified hyper-feminine body, the curvaceous and the flat, to name them as flesh — is the mirror.

The mirror of my desires, where what counts is the gaze we turn onto the reflected self, to judge it and measure it — the gaze that is not distracted even when the mirror isn’t physically present. Because there is an inner mirror, cold and judgmental, where the body we’d like to have, the wished-for body modeled according to fantastic abstractions, is compared to the warm carnal body we have inherited by birth. The body that holds the traces of our aesthetic history — a grandmother’s pronounced nose, an uncle’s light blue eyes, a mother’s hands, the curls passed down from generation to generation – and that is also an inheritance to accept or refuse: a body, or a part, that I love in its imperfect form or that I find intolerable because it reminds me of someone else. The body is multi-layered memory and it is always the product of a chorus of blended voices.

Does it make sense, in this assemblage of projections, reflections and images that saturate our vision of the beauty of the female body, to search for forms of truth? I’m not thinking of an absolute truth, one that could become the foundation for a collective ethics. For this would risk turning into censure or sanctions against those who practice the ’“artificial” instead of the “natural”, two poles that are in reality increasingly confused by the advance of a common feeling advocating the “natural” while achieving it thanks to the highest degree of technological and media sophistication…

Rather, I’m thinking of the inner truth that tries (insofar as is humanly possible) to make the wished-for body match the one we possess. With the passing of the years, as I approach old age, I interpret them and experience them more easily as the “deep” and the “superficial” that co-exist in a single body. The beauty of the deep body is its power as an organism alive and open to sensation and emotion. The other, the superficial body, is the two-dimensional one of fantasy, of the imagination in all its forms: from adolescent daydreaming to the consumer fiction of the perfect faces in face-cream ads, to glitzy models (the latest substitute for film stars and beauty queens), to the photos of common people who smile at us on the web.

I meet my deep body with more serenity now that with advancing age the surface patina of beauty is growing thin. And after living through the time of youthful beauty with difficulty and even dramatically, I now walk calmly in the time of its progressive, inexorable disappearance.

My looks no longer depend on me: the passing of time etches and fades my face, exhausting and deforming it. The course of old age is more marked than any other sign, stronger than any cosmetic barrier, more myself than any make-up I put on. And the make-up, the anti-age creams, the hairs bleached to confuse the blond with the white ones, become a game impossible to believe in, a little daily carnival, a lottery with unexpected trifling winnings and guaranteed losses that have already been taken into account.

In certain wrinkles I find my grandmother, in the white hairs my father, in the lined nails my mother, and I feel both troubled and tender about this. My spirits are lifted and I am reconciled to a body that I settle into more comfortably than when I was younger. In the economy of inevitable loss, I get back what I wasted when I lived in an excess I couldn’t fully value: the final paradox, and the happiest.

TO BE CONTINUED

Also, read Wonderful Breeze, by Riccardo Olivieri, translated from the Italian by Patrick Williamson and published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments