As the holiday season closes in on us, Rebecca, who has had her works published in several art and literary journals across the globe, poured her heart out in a conversation with The Antonym.

Atrayee: Please tell our readers when and how it all started. What inspired you to become an artist?

Rebecca: I think there was a lot to fall in love with, in children’s books. They are, I think, the magic boat which draws you in. Not to mention the magic-service they perform for the stories they accompany.

Atrayee: Let us talk about your paintings. You seem to work with oil a lot. Is that your favorite medium?

Rebecca: Yes. It has a beauty of its own. You may even actually add quite a bit more oil to the oil paint, as you paint.

Atrayee: And what about your process?

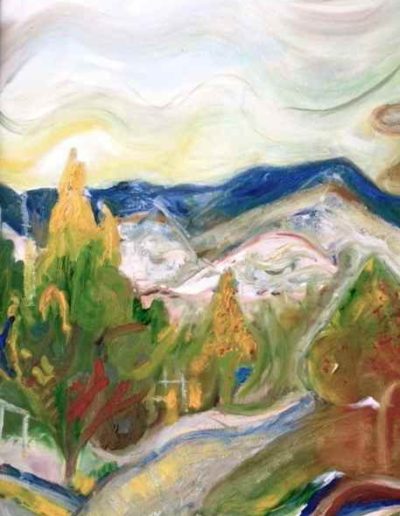

Rebecca: I like a painting to be done in a day, but usually, it is not. I try to set it up at a distant point, where I continually see it, on its easel, notice it, out of the corner of either eye. There is a tall, purely-glass door beyond where I work. I often set a painting just behind that glass door, outside, so it can be seen from a thirty or forty-foot distance, in shaded, but brilliant, natural light. I’m asking it, in my head, if it’s done; it’s telling me it is, or it’s not. It’s better to underwork than to overwork. Usually. Though mosaics, textiles, music, all remind you that the intensity of (repeated) intricacies can be a good thing, too.

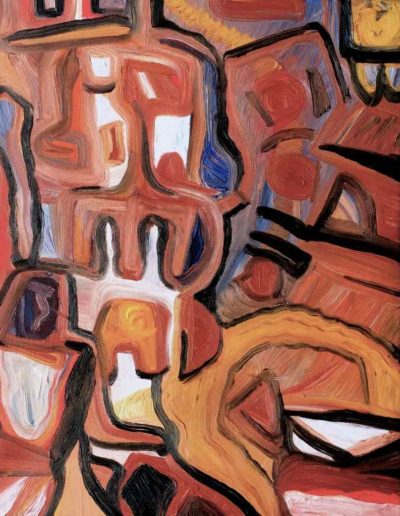

Atrayee: Your subjects revolve around neighborhood buildings, common people, and everyday objects. What are you trying to say through them?

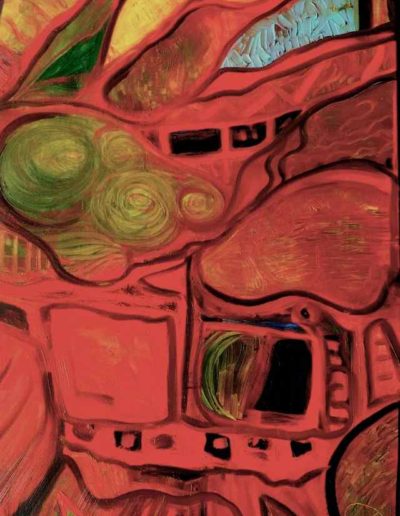

Rebecca: Artists talk about light, but you would be surprised by how much an artist is searching for what is created by shadows. All buildings, trees, people have around them aura after aura of shadows, borrowing or trading with the colors around them, reflected or retained. Buildings, people, trees, everything, has a distinct collection of shadows and reflections. They’re all rich with them. As rich as they are—with light.

Atrayee: Speaking of light, you are a photographer too. What makes you take up the camera? How do you decide if a specific experience/idea needs to be captured with a camera or paintbrushes?

Rebecca: “Look at me”—a black and white photograph has said to you, the photographer. “Look at me seriously. And, if you really are serious about me, let me be black and white. Let me be more real than real. Notice everything about me more intently than everyone else notices me; make me serious, make me black and white.”

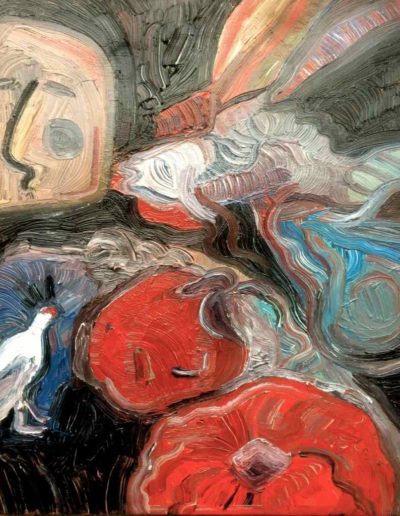

A painted expressionist canvas, in its turn, has said something different to you, the painter. “Me, please,” it says. “Why not? You yourself—can even choose every color. Choose everything about me. Mix dreams, worries, memories, the future, too. Let me be truer, please, than ordinary reality.”

And so—the fun is both are imploring you to leave basic reality.

Atrayee: While you are generous with colors when it comes to painting, is this why you seem to prefer black and white tones in photography?

Rebecca: For designs, patterns, which you really wouldn’t notice at all, if color was present.

Some of my paintings, even, I prefer reduced to a sepia tone or even a dull, ashen, black and gray and white. A painting of mine, The New Parts, about to be published in a journal called Kithe, out of Portland, Oregon, is a sepia tone. It looks good. In an issue of Gulf Stream, recently, one painting of mine, Gunsmoke, appeared in black and white.

In paintings or photographs, there is a much more serious feeling. Without color. Color photographs can become chaotic—festival, party colors. And, as mentioned above, unless you subtract color, you’re not in charge of colors in your photographs, other than changing densities of hue.

That word “hue” reminds me of how I recently noticed your journal refers to “hues” of poetry. That’s marvelous!

Atrayee: You are not just a visual artist. You write as well. Can you tell us a little about your experience as a writer, and how it blends with your creative pursuit?

Rebecca: I am lucky, drifting as easily into drawing or painting as writing, though, when I was young, this burdened me. What was I to be? Artist? Writer? To be one, I thought, you had to abandon the other, or at least most of your seriousness about the other.

Only after meeting many artists who are writers, and writers who are artists, did I understand it’s double gift, double burden. Both draw from the same hungry bank in your head, yet, different sides. Thus, I’m two. The part of me which is an artist is jealous when my writing is chosen to appear somewhere; and my writerly brain is envious when paintings by me are chosen to appear elsewhere. But often something I have written prompts a painting; and very often, something I have painted—prompts a written piece.

And they can even appear together, in one art/literary publication. But not terribly often. That, really, is probably too easily perfect.

In journals, written and visual pieces jarring anew against each other, do create surprise, a dissonance, which enhances, usually, both (sorry, the last part of that line sounds as if I remember it from a textbook). A delicious, accidental collusion, the two of them, meeting each other, and now wonderfully, fatefully, together.

Atrayee: Just as you effortlessly travel from painting to writing, you have lived and worked in several places too, including Alaska and London. What were you doing there? Did your journey to all these places have any lasting effect on your art?

Rebecca: In Alaska, I was a child. But in my opinion—that was the very best time for me to be there. Unforgettable. I am sorry for those who do not know it as I knew it.

London was a place I chose. You will laugh, but it was Disney’s Peter Pan which probably truly most made me want to be there. And return there, which I have done many times, and will continue doing. That Pan-view of the city as he flew above, overhead, and below it was twinkling and blue and golden and unfolding, village upon village forming one city, the endlessly curving streets with minds of their own, almost like rivers! At least as magic as the wild but newly-settled North.

I have lived many other places, too. All travel is formative. But they are long stories. I’ll stop here.

Atrayee: The Peter Pan connection makes sense. So, Rebecca, is there anything you want your art to accomplish?

Rebecca: Accomplished already: frees you from ordinary world. Lets you assess and ponder much more richly. Studying art and art history when you are young is the richest of experiences, full of people who think differently than anyone else you’ll meet. Helping you, in any group of people, to feel free to think differently, either in the present moment or in the past and future, and be proud.

A writing group I was recently in, for a period of years—made me grateful each time I was with them that I was/am an artist. All your life, talent will separate you from others, draw suspicion and envy. But it’s all worthy of envy, and in the long run, that separation protects you.

Many ideas they had, such as putting little identical check marks all over manuscripts, urging each other to make all tenses match, using computerized novel-writing guides, were almost childishly circumscribed, what can happen to you if you work at a job where you must wear high heels, take orders from companies or schools or clinics or haircutting salons or libraries, or, over decades, religious institutions. Most of them sharply envied my almost bird-like freedom, my happiness, my great good fortune not to have to labor as they did.

Art is a higher calling, a higher church.

Atrayee: Studying art and art history is indeed the richest of experiences. I second you on that. Is there anything you enjoy doing when you are not creating art?

Rebecca: I think you’re always doing it even when you’re not doing it. Storing away. Even as I answer these questions, I’m thinking of a painting I should have painted weeks ago. But haven’t.

What do I enjoy? Is there anything in the world greater than a movie? Subtitles making you study people’s faces closely, another language leaving only a wonderful musical impression, another old or new country the movie’s both letting you see, and somehow also be in? Catching and stopping in-time the actors and actresses and the stories of writers—as if a still life, but moving. Just like making a painting, really. In many ways. But more.

But I don’t see enough films. I’m frightened about possible—disappointments? By the end of my life, I’m sure, I won’t have seen enough.

0 Comments