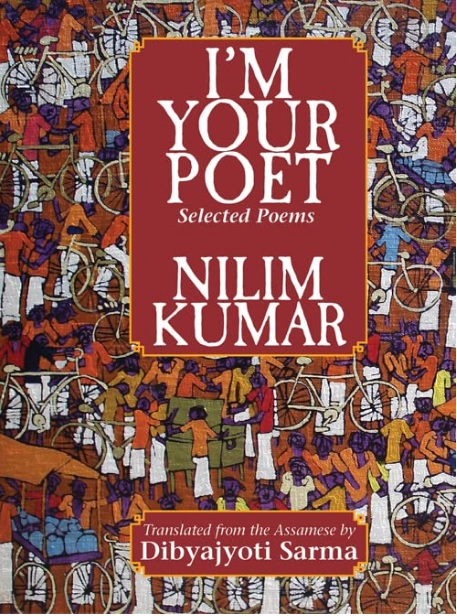

A book review of I’m Your Poet (Selected Poems) by Nilim Kumar, translated from the Assamese by Dibyajyoti Sarma

In her essay, Translating into English (2005), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak postulates the translators’ responsibility to grasp the author’s presupposition. This is imperative for the translators to enter the protocols of a text—which, according to Jacques Derrida, is “not the general laws of the language, but the laws specific to the text”. This exercise, as Chakravorty says, makes translation “the most intimate act of reading”.

If we take up from this point, we can claim, the most intimate act of reading leads us in two different directions. To explore the first; we better read two poems by Assamese poet Nilim Kumar in Dibyajyoti Sarma’s translation:

My Own People

So, the field wasn’t even there,

crossing which, all those days,

we had gone to that village

My own people stayed in that village.

When we went there,

carrying umbrellas of sunshine or rain,

they’d wait for us in the field.

While returning, they’d

come with us to the very field

which was never there.

So, the field wasn’t even there,

crossing which we reached the village.

And so, even my village,

and my own people there,

they too were never there.

The second poem is:

Home

I had left her here

as I went to meet my mother

didn’t find my mother,

she’d gone visit my father

returning,

I didn’t even find her here

mother did not find father either

returning, she has entered the house

I too did not find her

returning I’ve entered the house

When a poem succeeds in touching its readers, it ensures that the readers are drawn within, into a kind of self-contemplation. This is possibly the highest level of appreciation poetry can bargain for itself. However, the general tendency is to go further to connect the text with memories, dreams, and even other works of literature, eventually multiplying the layers of implications it comes with. When we read these two poems, a lingering and simultaneously intangible pain in our memories is provoked, even though most of us have not had the same experience/ tragedies in our lives. Is this not an intimate reading?

Yet, the intimate act of reading that Chakravorty refers to does not concern itself so much with readers’ response. Here, we see the other direction: translators can never be allowed the luxury of the creative liberty enjoyed by a common reader. Their attention should be fixed on the authorial intent. We know what the most this intimate act of reading is capable of rendering: a text’s essence in its most unadulterated form. The translator is never expected to replicate the source language in the target one.

In his conversation with Anindita Kar, included in I Am Your Poet, a compendium of Nilim Kumar’s poetry, the poet comes up with one of the most common answers on the issue of translation: “The main task in translating a poem is to preserve the essence of the poem”.

Now, we ask ourselves the basic question: What is this essence? Is it the translatability of a text? Where does it exist in a poem, and in which form—an idea, philosophy, or an image?

In My own People, the word ‘there’ is used six times—hinting at the poet’s view of the village from outside. The poem further questions the very validity of the poet’s memory of the village where his own people stayed. The second poem, Home uses the word ‘here’ only once—and, to put it in a prosaic manner, that highlights the nonexistent (or, to be more accurate, now-extinct) ‘inside’ of the poet’s world. The title is Home, instead, the poem uses the word ‘house’ twice. Underlining the fine line of difference between the two words effectively must be counted as one of the achievements of Sarma’s translation. Do we not know what stands between just a concrete structure and a place for the family? The second one feels alive.

We can conclude that the sense of loss and displacement both poems evoke conjures their essence. It is not merely the ideas translated or the words—it is everything coming together when we can’t tell the elements apart. However, in any argument pursued about translation, these two very terms—‘a sense of loss’ and ‘displacement’—are bound to recur at one level or the other.

While reading a work in translation, it is often forgotten that for a text it is a prerequisite to thrive on and enrich the tradition of the language it has originated in. A country like India with its unique multilingual matrix is bound to depend on a lingua franca to get the texts of its regional cultures across the board. But, the specific common language, playing the role of the medium, should never be allowed to act like an equalizer, overlooking or bulldozing the nuances of the regional languages to appropriate the text for a smooth translation. We must acknowledge the fact that there is a possibility of all the cadences in a particular regional language not fitting within the scope of the target language. Demand for this acknowledgment gains the status of strong political resistance in our country’s present context. But, quite obviously that does not mean if a poem written in a regional language has universal appeal, it beats its purpose. Making the readers self-aware of poetry is sufficiently a political act in itself.

The book’s title, I’m Your Poet gives us a clue about the flamboyance in the tone of Nilim Kumar’s poetry. Published by Red River in 2022, the anthology is divided into three sections, only consisting of Sarma’s translations: The Garden of Sleep, I’ll Start Loving You from Tomorrow, and These Two Hands. The collection also includes Nilim Kumar’s translations by Nabina Das, and Anindita Kar, though fewer in number, comments on the poet by Ravi Shankar N and Subodh Sarkar, and a conversation between the poet and Anindita Kar.

Though there is no prominent line of demarcation between them, the three sections of the book, in a broad sense, are different from each other in flavor. The Garden of Sleep is themed chiefly around the art of poetry. The second section consists of love poems that constantly test the limits of the subgenre. The third one dwells heavily on a languishing nostalgia. Nilim Kumar’s poetry can be characterized as startling. It will be a great pleasure for the readers to discover how, or in how many ways the poet can startle us. His poems sometimes appear forever doomed to a helpless longing for the past:

Inside his heart, innumerable fields, a pond full of blue lotuses,

Song of silent stones, a lake of sunshine going up in vapour,

and the geometric peaks—all collapsing into themselves.

He knocks on every door of beauty and journeys

from darkness to grievous un-present…

(The Angel)

In nostalgia is preserved the essence of the poems like The Fishhook, Childood. Then there is an irreverent, bold poem, Ruby Gupta, which erupts with rage:

Ruby Gupta’s underwear was still wet on the day

of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre…

Her undergarments remain wet for days

and there are earthquakes, volcano eruptions,

Tsunamis, and killings…

Prurience is the tool to cast a slur on society. In belching out angry, slanderous, provocative comments, Ruby Gupta is a tailor-made ‘political poem’. In the second section of the book is a poem titled Robot that takes satire to a different level. The poem verges on belonging to sci-fi, principally for the characters it deals with feel familiar in the genre:

a male robot

falls in love

with a female robot

they make love

by pressing a button

they have a button

for kissing

and a button

to forget each other

when they are at work

This is not a poem about the machines; instead, it is one about what plays the role of absent referent in the text—humans. It is the humans who suffer for the sheer presence of memory in them. Right next to this poem is printed the poem titled Button:

I’ve lost a button.

Do you have the button

on you?

You said once

all my things were yours.

You said even if I’m lost

you’ll find me.

do you have my button

on you?

Stitch it,

stitch it on my shirt,

that fallen star.

Printed immediately after Robot, this poem unfurls itself in a different dimension where it becomes both funny and profound simultaneously. In Robot, electronic buttons are used to regulate the emotional activities of the machines. And, in Button, the lost button of a shirt, compared to a fallen star, stirs up the passion between a couple. If there is only one thing amiss in this book, it is the dates of the composition of the poems. Robot and Button, juxtaposed cleverly, have their respective approaches to the same point—life—from two opposite directions. Information about the one that was written earlier could have projected the course of the poet’s journey with more clarity.

Nilim Kumar’s style has a charming effect on the readers. Even when he is writing about sadness, irritation, disgust, or anger, an attractive playful attitude never ceases to entertain us:

Leaving home on the car,

Suddenly I forgot where I was going.

Then hurriedly I get into a traffic jam.

There I get anxious and

I remember where I was going.

A lot of people tell me,

I saw you in the traffic jam today.

Yes, to remember who had seen me

in the traffic jam,

I have to get into a traffic jam.

Flashes of satire are there, but the anger behind the attitude is never corrosive. The poem’s title is In the Traffic Jam. The terse expression about the real urban landscape is a funny take on the stereotypes associated with modern times.

Nilim Kumar appears very flamboyant in his portrayal of a poet’s profile. The poem’s title is The Poet:

one morning

a man

went to the seashore

and started to walk

on the waves

everyone thought

he would now drown

but he kept going

and the sea was ecstatic

There is a poem about love that meanders through a different path to land on a social message. The title is Customer:

thirty paise in the pocket

price of a cigarette

if I had a rupee

I could buy a drink

no money even to get drunk

what poverty

just have the heart

could I bargain it for some love

to get

drunk

This particular poem, hard-hitting, unambiguous, and sharp, seemingly mocks the clichés in our popular culture about a lover, and drunkard—come across in Bollywood films or songs. But, the flick in the title shields us against a threatening melodrama. Can we imagine the customer? We surely do, he is wearing a deadpan expression on his face and he fumbles for satisfaction in the murky mercantile world.

Quite interestingly, the book has left us with an opportunity of comparing two translators’ renditions of the same poem. One such is titled Rain. The first one is done by Sarma:

her heart

a tall hill

turning into a cloud

I touch her

sometimes crashing on her rocky heart

drenching the hills, trees

fields and houses

I come down

people think

it’s rain

The other translation is by Nabina Das:

Her heart

A tall peak

I become a cloud

to touch and see her

Sometimes I strike against her stone-laden breasts and fall

over hills trees vegetation fields and homes to drench

everything around

And people think it’s raining

The two versions, as we see here, leave us with almost the same impression of the poem. The words and enjambments differ but the lyrical nature of this surreal poem is conveyed successfully. In poetry, words create a kind of centrifugal force—readers are flung away from its center to the center of their respective existences. This discovery or exploration of the self is the real pleasure of poetry. From now on, the rain will never be the same.

Also, read two Hindi poems, written by Dr. Kumar Vishwas, translated into English by Moulinath Goswami, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments