A BOOK REVIEW BY OUDARJYA PRAMANIK

Jerry Pinto, an Indian prose writer, poet, translator and journalist, is a distinct voice in contemporary Indian literature. His work is characterised by its profound exploration of human emotions, societal issues, and the intricate details of everyday life. In essence, Jerry Pinto’s poetry is a tapestry of emotions, experiences, and observations that invites readers to explore the depths of human existence. His contributions to Indian literature challenge norms, expand horizons, and offer a space for readers to engage with both the personal and the universal.

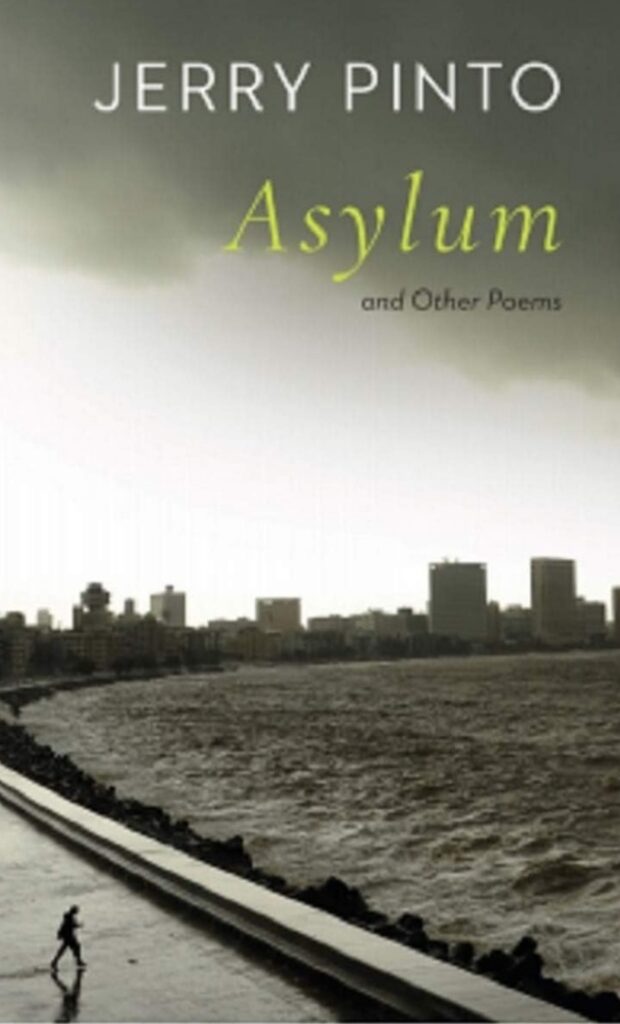

“Asylum” can be seen as an emergence of a unique voice in Indian poetry. Despite being featured in journals and anthologies, Pinto’s poems have largely circulated within reading circles and photocopies due to the prevailing trend of limited opportunities for poets in the mainstream publishing landscape. This “word-of-mouth tradition” takes on a fitting role in Pinto’s work, given his cadenced and speaking voice, characterised by irony, pain, self-irony, and melancholia.

Pinto highlights the exploration of family history and personal experiences in his poetry. The poems draw on narratives of family lore, escape, resettlement, and growing up, reflecting an archive of inherited attitudes and patterns. Pinto’s poems are positioned as a means of understanding his individuality and role as a poet while reflecting on his personal journey within the broader context of his family’s experiences.

Now, let us dig into the poem, “Asylum”, which happens to be the title of the whole collection later on. The term ‘Asylum’ usually refers to a place of refuge or safety, typically granted to individuals who are seeking protection from persecution, violence, or other forms of harm in their home country. But here, “Asylum,” delves into themes of confinement, decay, and the complexity of emotions. The imagery and language used, evoke a sense of unease and introspection. The poem opens with the image of a “chemical soup stilled,” creating a sense of stagnation and containment. The metaphor of a “harsh harbour” suggests a place of refuge that is not entirely comforting. The phrase “Becalmed, you loll at anchor” implies a state of inertia and vulnerability. The mention of “Barnacles cling to you; their slime-scented kisses” introduces a tactile and sensory element, underscoring the idea of deterioration and decay. The use of “rot shivering through your timbers” vividly portrays the physical and emotional effects of this decay. The lines “Your nails are copper-tinted, varnished, unchipped” may symbolize a façade, a polished exterior that hides inner turmoil. The “holes filled with pebbles, lacquered pink” could represent the weight of suppressed emotions, coated with a veneer of artificial beauty. “Asylum” shifts to a broader perspective, mentioning “alien mornings flecked red with maritime superstition,” suggesting the unknown and possibly ominous future. The lines “Our eyes sache with watchfulness; Of anchor, and sense and what love means” reflect a contemplation of identity and the nature of emotional connections. “Sleep is inevitable and the slippage” hints at the inevitability of vulnerability and the fragility of stability. The imagery of “sky screams” and “blowtorch is wise” intensifies the atmosphere of turmoil and impending crisis. The closing lines, “In the calm, the encrusted stains, blood, rust, mock those decisions. What watches us? Those holes we cut to still you, are those your eyes?” raise questions about the consequences of choices made and the haunting gaze of introspection. Overall, “Asylum” is a thought-provoking poem that invites readers to reflect on confinement, decay, and the intricate interplay of emotions. The vivid imagery and evocative language create a sense of unease and contemplation, encouraging a deeper exploration of the poem’s themes. However, the poem’s themes could reflect broader societal issues of isolation, the human condition, and the search for purpose. Overall, the poem appears to offer a metaphorical exploration of the individual’s inner world, societal challenges, and the quest for understanding and connection.

Now, let us not analyse the other poems of the collection, but overall we can say that, through his poetry, Pinto offers insightful commentary on societal issues. He addresses topics such as mental health, identity, and urban life, shedding light on the challenges faced by individuals in a rapidly changing world. His poems serve as a mirror to society, prompting readers to reflect on their own lives and surroundings. Pinto’s willingness to explore unconventional and often taboo subjects sets him apart as a bold and daring poet. He fearlessly tackles themes that are often overlooked or silenced, contributing to a broader conversation on subjects like mental illness and marginalised voices. His poems reveal a depth of thought and a penchant for introspection. He invites readers to engage with profound philosophical questions and existential dilemmas, prompting them to contemplate the nature of existence, relationships, and the human condition.

Pinto’s engagement with historical events and personal stories is evident through this collection. The fourth poem in this collection, “Exiled Home from Burma” draws on his grandmother’s memories during World War II, revealing the astute strategic thinking of his great-grandmother amidst turmoil. Pinto’s poems reflect his willingness to confront destabilising emotions and vulnerabilities, capturing moments of desire, self-confession, and introspection.

Pinto’s mastery in portraying the intersection of different realities is evident in “Dreaming at Mukesh Mills,” where a derelict textile mill becomes a backdrop for intersecting narratives. The sequence titled “Tree” portrays the urban trees of Mumbai, each symbolising both its botanical reality and a corresponding human predicament.

The poem “Well, If You’re a Poet, Write Me a Poem” is a thought-provoking piece that can be interpreted as a reflection on the creative process and the expectations placed upon poets. The poem seems to convey a sense of frustration and contemplation, as well as a cautionary message about the potential consequences of attempting to force artistic expression. The title itself, “Well, If You’re a Poet, Write Me a Poem,” sets the tone for the poem’s exploration of the challenges and complexities of creating poetry on demand. The speaker is presented with a request to write a poem, and they ponder how best to fulfil this request.

The poem, “Incident at Chira Bazaar”, describes a walk along a river with imagery of kindness, encounters with people, and a specific incident involving a drunk man. The poem explores themes of hospitality, social hierarchy, and self-perception. The speaker reflects on the encounter and questions the perception of divinity within every individual. The closing lines reveal a defensive tone, suggesting a confrontation.

We can come to the inference that there are two sides to Jerry Pinto’s persona. One side of him is a charismatic and witty figure, engaging with his audience through charming phrases and quick-witted expressions. This “people’s person” aspect of him seeks to delight and disarm, but beneath this lies another layer – a vulnerable, introspective individual who has experienced love, loss, and loneliness. Pinto’s poetry becomes the space where these two aspects intersect, allowing him to be both authentic and reflective. His poetry serves as a sanctuary where he can be his true self, without the need for pretence. Through language, Pinto merges his multifaceted emotions, experiences, and perspectives into his sentences. Drawing from his multilingual and multicultural background, Pinto infuses his poetry with diverse influences. This fusion adds a unique flavour to his work, blending Indian and Western literary traditions, languages, and perspectives.

His poems too highlight his exploration of Mumbai, his relationship with his mother, and the echoes of past loves. Additionally, it touches on Pinto’s grappling with the process of writing poetry itself, reflecting on both the tribulations and threats that come with the creative endeavour.

Also, read Stories of the War by Chantal Danjou, translated from the French by Dominique Hecq, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments