A review of the first part of the Chandal Jiban Trilogy, The Runaway Boy, written by Manoranjan Byapari, and translated into English by V. Ramaswamy

The first thing to hit the reader upon initial reading is the word rice and how the smell—lack or excess of it—controls the ebb and flow of the lives that the poverty-stricken Jiban witnesses in his long journey of 14 years.

The Chandal Jiban Trilogy is one of the most widely read and seminal works of Manoranjan Byapari, one of the most prolific Dalit writers from Bengal, one of the few who have lived to tell the tale of woe that struck the Namasudra community, one of the larger Dalit communities in erstwhile undivided Bengal, who had to face wide-place displacement following the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947.

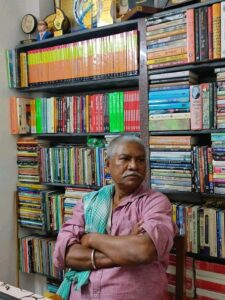

Monoranjan Byapari

In a manner reminiscent of the hoary literary tradition of the past where writers belonging to the Savarna began their stories after lengthy pronouncements by recalling their family glory and their forefathers’ exploits whereby lineages are brought forth before commencing with the present life of the protagonist, Manoranjan Byapari, in a manner of subversion, skilfully traces the plight and oppression of Jiban’s ancestors to his grandfather and his immediate and extended family. The story masterfully charts the mythic-historical origins of the Namasudra community, broadly categorized under the umbrella of Hinduism despite facing generational othering within its folds and the impact of religious aggression on them during the riots of East Bengal.

The story somewhat loses steam while narrating the ordeal the community faces under the unliveable conditions of the refugee camps set up by the government. Although in no way does it falter the pace of the general narrative—the back and forth, revealing a similar set of circumstances as experienced by Jiban and his father and community elders. It does not, in my opinion, hinder the general flow of the narrative, although it considerably shifts its focus from Jiban’s family.

However, the introduction of Maran, the mirror image of Jiban, introduced during this period of turmoil, who keeps him alive and provides the mantra of survival—Charuibeti or keep moving—that reaches a moment of catharsis only towards the end of the narrative, is an echo of the omniscient narrator whose somewhat similar trajectory of life breathes vigor into Jiban’s endless search for dignity in a wretched world.

In the meantime, the story moves restlessly following Jiban’s exploits and the exploitation experienced therein in a fluctuating yet lyrical manner with moments of deep reflection and introspection in the face of grave pain and dejection which shadow Jiban’s life till the final pages of the book. The story in the second half mainly unfolds across a comparatively vast timeline where the author notes in a third-person narration, the political and social upheavals rocking an infant nation facing the still-fresh horrors of Partition, the war with China, and the Maoist insurrection in the latter half of the mid-1900s. In a wide arc, the narrator, through Jiban’s various traumatic encounters with all manners of wicked and perverted men—starting with doctor Hem Chakraborty and his superstitious wife, the homeless boy Raja at Sealdah station, the tea seller Binoy Saha, the havildar at Siliguri station—encompass the vast yet unfortunate length of the journey undertaken. It starts from the family’s journey to Burdawan, the difficulties of Siramanipur camp, and moves on to the backbreaking poverty of Khola Doltala, to the mirage-like city of Calcutta, the various rail stations where Jiban wanders like a wraith, to his numerous journeys to Siliguri, Assam, Darjeeling, Lucknow, Kanpur, Delhi, Agra, Allahabad, Mathura, Kashi, Vrindavan, Haridwar to come back to square one, browbeaten and tormented. With Jiban, the reader gets to know the wide unrest and confusion desperate people were thrown into at the time of the birthing throes of a newborn nation. We also learn that Jiban’s family and those like him suffered the most terrible of those nightmarish consequences of being at the fringes of a ‘respectable’ society.

The first part of the three book Trilogy is placed squarely at the intersections of the long journey and uncertainty of Partition followed by forced rehabilitation imposed by the government on the Namasudra refugees of East Bengal, seldom of whose narrative is highlighted and as greatly exaggerated as those of the upper caste settlers of Bengal in the light of the many personal and humane tragedies that continuously marked their lives. By focusing on the political, social, and individual reactions of people and their communities on the numerous instances of communal violence, racial violence, and similar experiences of caste violence witnessed by Jiban, we the readers face head-on the soul-crushing lack of empathy and mechanical functioning of a metropolitan city, alike in their indifference to poverty and youth.

Without any respite, the omniscient narrator throws his implied readers into the deep recess of Jiban’s mind as we experience with him the horrors of living as a Dalit child without any support or sympathy in the harsh realities of a modern yet unkind society still clinging to the last vestiges of Brahminical and caste hierarchy at the expense of humanity and kindness.

The lamentations of the narrator looking through the eyes of Jiban at the merciless world cries for redemption and some light of hope which forever seems to hang as a beacon in the dark choppy waters of Jiban’s turbulent young life.

The translation that I referred to has been published by Eka and the translator they have chosen, V. Ramaswamy, has done justice to the complex wordings and cultural expressions that fill the pages of the book. However, I wish he had kept the regular syntax of the language intact while narrating the conversations between the Namasudra refugees of East Bengal, the Bengali-speaking Muslim community who were also equally dispossessed of their rightful social status as equal citizens, and the upper caste bhodrolok gentry that Jiban and his family keep coming across at numerous sections of the text, for survival and service.

Otherwise, V. Ramaswamy, who is well known in the Kolkata translation and intellectual circles, is a non-fiction writer and translator. He has been an activist and worked for the rights of the laboring poor, and has written about workers, squatters, slums, poverty, housing, and resettlement, and has been at the forefront of rebuilding his city, Kolkata, from the grassroots. Although a Tamil, he has developed a thorough knowledge of literary and colloquial Bengali and has done competent work with reading between the lines and conveying the bursts of fleeting joy and long days of perseverance against the greatest odds in Jiban’s life. His target readership can conceive the great depths of emotional and physical upheavals in the lyrical prose of the source text in the final translated work.

It is a story of Jiban’s plight, his flight, and his endless search for a home outside of the normative sense of the word. It takes the reader on the perilous path of self-doubt and forces one to reckon with the many moments of thoughtlessness one unknowingly inflicts on those we condemn to be on the margin. The author painstakingly paints a canvas where the smallest sensitivity or the lack of it can make and break a person’s ethical core in numerous unfathomable ways, thus leading to the continued destitution of generations of people who under a twist of mercurial fate, have been denied the very chance at life. I felt hopeless and bereft of catharsis towards the end of Jiban’s long journey home, but I would urge the readers including myself to keep moving, Charuibeti as Jiban’s immortal tortured self exhorts him time and again, the refrain that echoes through the expanse of Jiban’s tortured existence—because only when we move do we realize that we are alive, otherwise what was the point of having come this far with Jiban in his endless search for a home.

Also, read six Turkish poems written by Behçet Necatigil, translated into English by Neil Patrick Doherty and Gökçenur Ç, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments