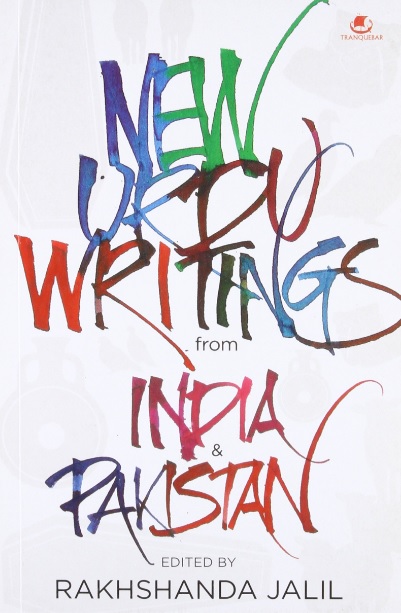

A Book Review of New Urdu Writings: From India and Pakistan (2013): An Anthology of short stories from the subcontinent, edited by Rakhshanda Jalil

Publisher: Tranquebar

The words ‘New’ and ‘Writing’ in the title of the book are general terms and can mean more than the editor might have had in mind. But let the lay readers get baffled and look for types of their choice contained in the word ‘writing’: essays, articles, poems, etc. The book contains none of these. It holds within its cover only the most popular genre of modern times—short stories. That too, stories translated from original Urdu, a language as rich in this genre as any European language. Urdu short stories have crossed miles and miles in a short span of a decade. For me, the book (though published a few years ago), can reactivate the imagination that had lain dormant because of the lack of literary activities in these times of political and social anarchy the world over.

The short story has reclaimed its space as an important genre with publishers and readers. A good story sticks in some crevices of the reader’s mind and one remembers it in moments of solitude affording solace to his tired soul. It is like taking a peek into a different world other than one’s own; in the translated version, that covers customs, traditions, and ways of life. The similarity within dissimilar worlds may appear dichotomous, experiences familiarly strange, and viewpoints from the infinitesimal rise up to widening the horizon of thoughts. Whatever they may be, the emotional appeal in such a short space cannot be expected from any other genre. Translated stories are getting popular day by day, especially in the regional languages of India. Urdu stories are also being appreciated by non-Urdu readers as never before. Four stories in the volume are translated by the editor herself, the rest by a series of translators, some of whose translations are readable.

Rakhshanda Jalil, the Editor of the Anthology

The thirty stories, selected both from India and Pakistan and divided equally, are from the new and not-so-new writers, for some were born even before the country was partitioned and the borders erected. The reason for the selection of these stories is not known nor do we know of any theme behind the assortment. But in a sense that provided space to include wide-ranging and memorable stories like Khalid Javed’s Mourner of the Feet where the shoe is the narrator, and Khurshid Akram’s The Slaughterhouse Sheep, in which we get to know the feelings of the sheep being led to the slaughterhouse. The word ‘new’ has been used for writers who have reinvented their art or experimented with the form, but they are not many. Otherwise, some writers who published their works years ago cannot be treated as contemporary or ideas topical, and yet their stories have not become worn out. Basked in the sunlight of the passage of time, they have mellowed to glitter with a new shine. But only a few read them again to find new connotations hidden behind words and beyond the thoughts In Zahida Hina’s story Kumkum is Fine, possibly a young lady doctor posted in troubled Kabul reads a letter from her grandmother only to be swayed by the past and the power of the written story: “The whole world loves the story of Rehmat Kabuliwala written by our great grandfather,” the character says. “But in our home, nobody talks about it except you and me. You remember that story because you were its heroine, and I remember it because I have heard it so many times from you, sitting in your lap.” Hina, a master in the technique of storytelling, possibly sets the atmosphere and ambiance for the book. Stories have to be written, talked about, and heard, in order to be a part of the fictional world. There is another aspect worth reflecting on tales and their delineation. In Khalid Javed’s story, it is the shoe that asks the pertinent question: “How is a story narrated? Does anyone really bother to listen to someone else’s story?” A story has to be told in some way or the other. But does that mean it would be listened to by those for whom it is meant? What about the writing process? Anjum Usmani in Somewhere, Something is Lost shows the writer struggling to write a single story and remaining unsuccessful till the end.

The fifteen stories from India seem to be like a view from a train window that had stopped for a while as in S. M. Ashraf’s The Hynea Falls Silent. The stories cast a glance at life that appears surreal and nightmarish. Sexual abuse, pain, suffering, trauma, and death haunt in the background. The dark atmosphere of the Jacobean tragedy seems to have been reinvented here in some of the stories. The contemplative mood ponders over death, rather than life, out of which little or no meaning emerges. In Noor Zaheer, a mother kills her own children, while in Tarannum Riyaz’s story, two children stay with a mother who is already dead. Faiyaz Riffat narrates about three men who died after a riotous night’s revelry and in The Last Show, the man in the circus is devoured by the lion. Similarly, in Anees Rafi’s The Curfew is Strict, the curfew itself is a kind of violence. The characters huddled up in a room talk about some injured men coming out of the debris of a house. “I do not know about life and death,” says one. “I am unable to decide whether the fearlessness on their face(s) was of life or of death.” Fear is ingrained into the texture of the story where decay, dilapidated buildings, broken glasses, and bats colliding against books are a part of the sense of defeat for the characters as well as the whole community.

It had been the prerogative of creative writers the world over to venture into the inner recesses of the imagination to throw light on the mundane world of men and even animals, as in Joginder Paul’s experimental story where fiddling with technique, the writer crosses the borders that separate a man from his dog. A story writer who had lived life for others is now on his deathbed. His interaction with the dog at times, and at others with his own soul, and then vice versa, is experimentation of a unique kind: man, altered soul, and a dog that understands the language of the unspoken. It is a venture into a surreal world that may exist between life and death. The modernity of other writers in the collection in technique and thought, adds a note to a song that appears to be somber and is sung without the accompaniment of music.

Pakistani stories are an amalgamation of the new and old, in thought and technique. They are national and global; tales that undo the disconnect that had developed between the peoples of Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Zahida Hina takes up a Hindu character who goes to work in a Muslim country. In Salma Awan’s By the Time You Know, a man from Punjab falls in love with a woman from Bangladesh: “drenched in insatiability—incomplete, unfulfilling,” are the words taken from the letter in the story that may make us understand the tone and tenor of these diverse stories. Most of the stories explore the insatiable search of man for things they do not understand resulting in unfulfilled dreams and unfinished tasks. Whether it is Ahmed Hamesh where the story does not come out with any substantial meaning or the man trying to cross the road in Azra Abbas, where he fails to understand whether he had crossed the road, or the traffic is still; they all remain unfinished, insubstantial and meaningless. The unfulfilled dreams are best exemplified in the story where a woman arrives in West Pakistan with her teenage son only to find that the man she had pined for is no more. Hamesh’s A State of Emergency leads one into a world where the search for meaning is like chasing a hen in a crowded traffic of an urban city. Yet out of the maze of bizarre events, strange characters, shifting scenes, and the surreal world, an abrupt end shakes our existence. These stories are ventures into the psyche of the twenty-first-century modern mind of a man; sad, bewildered, and alone.

The stories are also a patient wait for something or the other, like a father waiting for the arrival of his son in Mansha Yad’s The Eyes of Jacob. The father is happy to hear the news of his son’s arrival from a foreign country, yet he prefers to wait. “I prefer waiting for him…” Two characters destined to live till the end of time in Parveen Atif’s story, wait for the arrival of a new life. The Bangladeshi woman goes on waiting for her man from Western Pakistan after he goes away, never to return.

Azra Abbas, on the other hand, in three short stories, explores the death and dilemma of animals rather than men, like a rat and a chameleon. The rat dies because of the burden of its sadness and the chameleon is caught between the games the boys play for which it has to pay dearly.

But the universal themes of love, time, and fantasy lurk in the background. At times they overpower feelings of death, decay, or surreal ideas and linger over the imagination for a long, long time. “Has time stopped for them?” asks the character in Vanilla Crumble by Asif Farrukhi. “Or does it march alongside, woven into the warp and weft of time.” It is life that ultimately wins over death and the vicissitudes of time. Though the story is about cakes, it takes us into the past as never before; lanes and by lanes of history, and man’s romantic fascination for the past. The story will be remembered when all the other tales would fade from memory. For it is man’s undoubted fascination for re-enkindling days that had slipped into the sands of time.

Mirza Hamid Beg in his Mughal Serai does make time stop for a while and enter into a world that is in between dreams and reality. Here the borders of real and unreal, dream and reality, fact and fiction, strange and beautiful get blurred to arrive at a world where fantasy is more real, and life stranger than fiction. Beg possibly takes a leaf out of Alice in Wonderland but weaves a pattern into an Eastern extravaganza that almost existed before evaporating into the world of dreams.

Taken as a whole, the stories focus on the joys and sufferings of the individual, their dreams, aspirations, and frustrations. They explore the complex and multifaceted mind of man in different situations in order to understand feelings and emotions that had been, and would be again, though times change, or technology makes the world turn upside down.

Also, read a book review of The Runaway Boy written by Manoranjan Byapari, reviewed by Ahana Bhattacharjee, and published in The Antonym:

Charuibeti Or To Keep Moving Ahead With Jiban— Ahana Bhattacharjee

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments