Translated from the Hindi by Debalina Roy

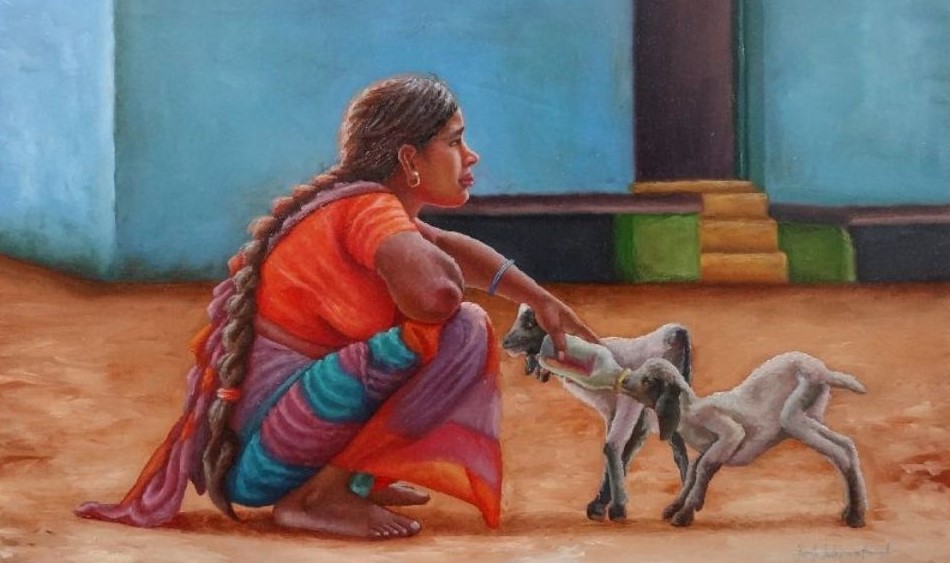

Image used for representation.

Honored Maasahab,

I bow down in reverence.

Perhaps you’ve heard of it; if you haven’t heard already, you will hear about it.

You will possibly receive my letter after three days.

The result of the election has been announced. I don’t know how things turned out the way they have.

When I think of it now, I am still as amazed as I had been on the day of winning. I never thought of being chosen for the post of chief.

How did I get so many votes?

There were party politics in the village. People were against me. Then…?

Later, I unearthed the reason, when I saw all the women in an ecstatic mood together. A glimmer of happiness was radiating from their appearance.

Being the wife of the chief of the block, I couldn’t possibly go from one house to another and thank my sisters, that’s why I reached the women’s cell. You must know that in every village the women’s cell is a safe space for women to gather. With hands stained in mud and cow dung, these women would often relate their personal experiences to one another while preparing dung cakes.

This place is a primary witness to our joys and sorrows.

Although my visits to the women’s cell weren’t considered suitable.

Ranveer had told me already that I did not look agreeable holding a pot of porridge on my head like the other village women. After all, I was the wife of a chief. When he became chief, the restrictions became more stringent. And when I became chief, his honor reached newer heights among the villagers.

He was seen as a husband with an open mind and a modern personality. Our village reached greater esteem with respect to other villages. And I became steadily pressurized by the instructions to maintain a dignified distance from the other women in the village.

Somehow, I couldn’t agree to this wholeheartedly and would reach that place and stay with them.

Ranveer used to say, your political age is less, Basumati! When you mature completely, you would walk away protecting your dignity.

Isuriya came along pushing a herd of goats at a distance. You probably remember because I had mentioned once that she is entirely unpretentious and really blunt. I also told you that she and I had come to the village on the same day after getting married.

You had laughed saying—”Didn’t you find anyone other than a herdsman’s daughter-in-law to feel affectionate? Wow, Basumati!”

She was very sharp. I had scarcely been able to raise my saree-covered face to see clearly the dry homes and apartments, lanes and neighborhoods; she had by then made herself familiar with all the doorways. She gauged every man she had seen. She wasn’t shy by nature and never shrank away. She articulated the names of the elderly and prominent villagers in a way as if she were their ancestors. She was absolutely liberated from unnecessary affectations of high-low, relations of near and far, and the complexities of caste and rank.

She stood shouting, “O Basumatiya! The king Ranveer’s bride! O the revered face!”

Everyone laughed.

She said, “Here you are, Basumati, look, everyone’s grandmother has arrived! Everyone is staring at you! Utter a battle cry, chieftain!”

She held a thin whip in her hands, and pushing the goats back, she came over to me.

She spoke with feeling, “You have become the chief. I am really glad.”

No one paid much attention.

She held the whip upwards and spoke passionately, “Hey, all you women, listen, listen with ears wide open! This is a time of equality. If the man beats you to a carcass, abuses you verbally, doesn’t send you to your parent’s home, all you sisters must head straight to Basumati.”

“Get a paper filed.”

“Put the notorious men in jail.”

“Hey, Basumatiya! You will not commit injustice like Ranveer, will you? You won’t suppress the papers, will you?”

“When Saliga broke my hands and legs, I immediately urged Leela’s son to file a complaint so that the men from the government listen to my pleas.”

“I had given Ranveer the papers myself.”

“In those days, Saliga would shiver. Why use hands, he couldn’t even mutter vulgar language for many days. But he roamed around like a lion once Ranna suppressed the papers and forced himself on my chest.”

He said, “Were you putting me in jail? Murderer, I have thought it through, even if I have to sell two goats, I will see an end to your papers.”

Throwing away the whip, Isuriya stretched out her arms. Putting her harsh words aside, the women folk muttered sadly when they looked at her wounded body riddled with scratches and gashes. The blossoming faces paled in an instant, Maasahab! Laughter and mirth had perished.

Gopi tried to laugh.

Pretending to smile, she said, “What are you blabbering? If somebody hears you speak these words, will he not report to the chieftain?”

But she was immediately overwhelmed with kindness.

“Let him listen! I am speaking because I want him to listen. Ranveer will grind the thresher and roll rotis in jail. And our Basumati will write official papers, give orders, and rule.”

“Isn’t it so, Basumati?”

“Say it honestly, you’ve studied till the eleventh, haven’t you? And hasn’t Ranveer failed the ninth class? Tell us then, who is wiser?”

“The days of the womenfolk being meek and tame are over. It is a time of equality. Hasn’t Basumati become a chief? It is the rule of Indira Gandhi.”

“Long live Indira Gandhi.”

Gopi talked angrily, “You fool, Indira Gandhi was dead long back. It is Rajiv Gandhi’s rule.”

“She has died?”

“So what? Is there any difference between a mother and her son? It is the same.”

“Why, when will the procession start?” she recalled suddenly.

“There was such a celebration when Ranna had become the chieftain. He was garlanded. People walked ahead with flags. Ranna had circled around the village on many shoulders.” Swaroopi explained again to her, “Oh you fool, why do you keep repeating Ranna’s name? The chieftain will put you in jail the very first thing.”

She recklessly jerked her head. “Listen all, listen to Swaroopiya’s words! Why Ranna, even your father-in-law Gajraj cannot put us in jail. Even your brother-in-law Panna cannot do it. Isn’t that so, Basumati?”

Also, read the first episode of a Bengali non-fiction by Hungryalist writer, Malay Roy Choudhury, translated into English by Sraman Sircar, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments