A LITERARY REVIEW BY SHRESTHA MUKHERJEE

As the clock strikes past the hour of dawn, the mist of newly decked-up day quivers in delight around the enigma of mountain cliffs. A bunch of workers who work in the fields, weave in exile and pluck tea leaves were sighted coming down, invading the fog swirling their path by singing their songs in disgrace and joy at the same time. Has anyone ever wondered what this emptiness is after they left, had something in them that they want to narrate? Has anybody ever heard what these hometown roads, the enormous northern pines, the mysticism of unbrooding affairs, roses and epitaphs, smoggy breathes, prolonged tears, March wind, cacophonic death and chaotic love are trying to utter from the hushed shadows shaking from the void? Despite its ongoing tension and violence at the very present, Manipuri literature is known for its captivating and intersectional field that studies memory accounts. Manipuri literature has always understood the concept of Memory Studies in terms of its scenic beauty, historical significance and cultural practices. Summing up the theme, renowned Manipuri Poet Robin S. Ngangom unveils whatever lies under the shroud of this mortal society. As a bilingual poet and translator, Ngangom projects the ‘carnal life’ as the essence of his poetry that revolves around political situations of the North East, societal discrimination, isolation and mundaneness of modernisation, and quests through a psychological retrospection.

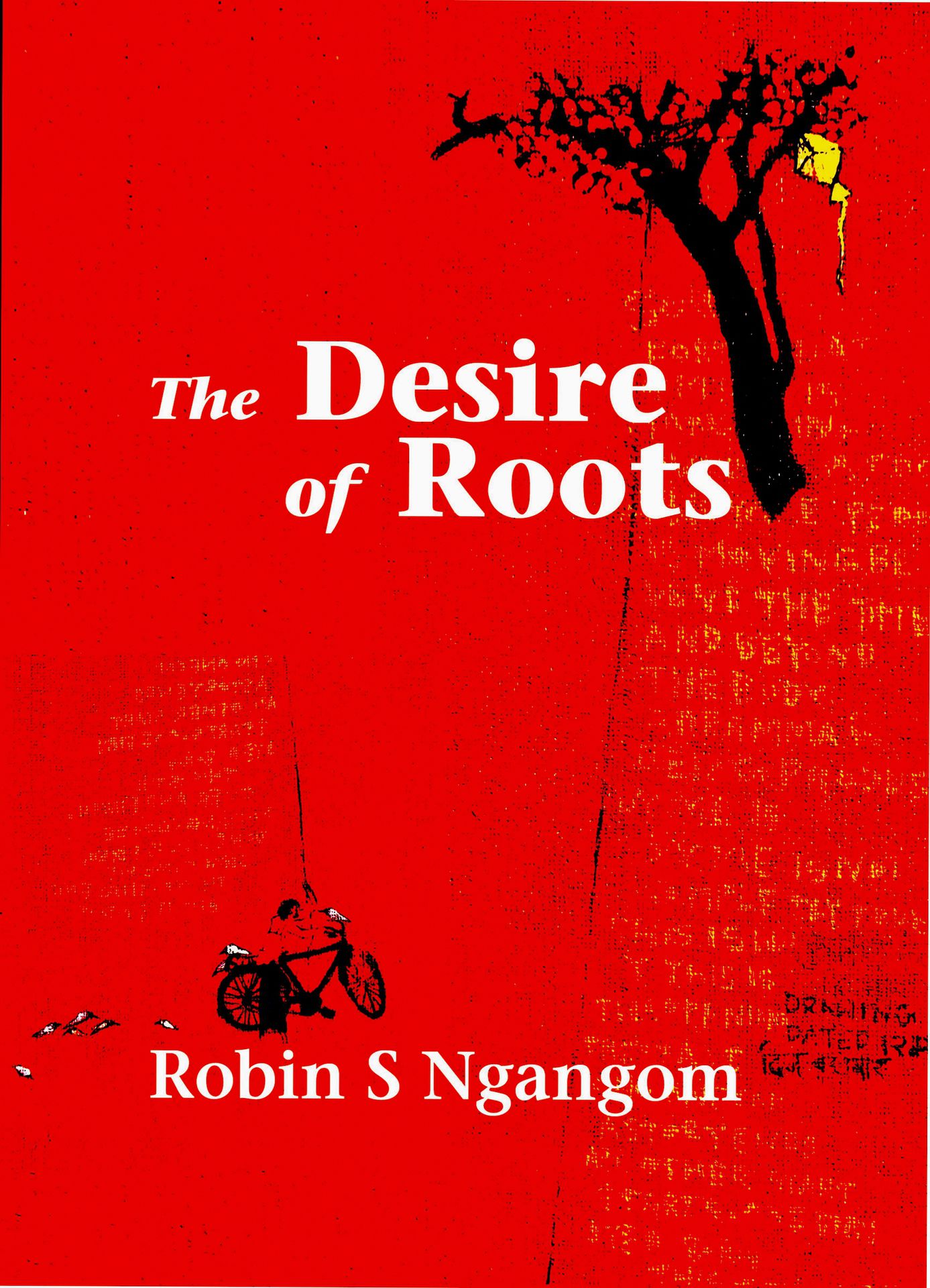

The Desire of Roots is the third poetry book by the writer. The book is a two-section collection distributed as ‘The Book of Lusts’ and ‘Subject and Objects’ that consisted of 48 poems and was published in July 2006. This anthology goes along the path of anxiety, obscenity and existent hostility. The French writer Jean Klein once said, “The root of all desires is the one desire: to come home, to be at peace. There may be a moment in life when our compensatory activities, the accumulation of money, learning and objects, leaves us feeling deeply apathetic. This can motivate us towards the search for our real nature beyond appearances.”

For the poet, memory works as the driving force to endorse personal growth. In this book, the poet primarily focuses not on the roots of desire but on the desires of our roots. Whether it seeks pleasure in the afternoon mist or broods in the vapidity of modernism, our desires seek no bounds. Neither did it learn from the past, nor they try to change anything. Ngangom has identified these roots as separate entities that try to communicate through nature and aspire to reach out to this mortal world. In the poem ‘Primary Schools’ from ‘The Book of Lusts,’ the poet celebrates freedom amid the wilderness of mountains and nature. He questioned the rigouring system of rules that cages the sense of children’s exploring minds. The epiphany of staying in the vanity of silence and holiday pleasures are two leading themes found in these lines:

“There were long delightful, convalescent afternoons

of illustrated classics without

the stress of the school bus when he heard

only the sleepy clang of hammers

in the nearby smithy, when life burn slowly

like calories even when he was sleeping,

without the solemnity of anyone’s life

coming to an end.”

Ngangom is an emphatic writer because he sees the vulnerability in the art of poetry. In some of the poems, readers will get the grave impact of the isolation and sombre of urbanic modernisation. Be it about the partial entity of mediocre livelihood or the paradoxical chaos that invokes the lonesomeness on the streets, Ngangom wanders around to seek his answers. For poems like ‘Poem for a City’ and ‘Middle-class Blues’ from ‘Subjects and Objects’ or ‘Street Life’ and ‘Shadows’ from ‘The Book of Lust,’ the poet has pictured a raw projection of urbanisation shrouded within the bourgeoise setting that regurgitates the monotony of living, heaving as a burden for the humankind.

“The middle class never begets rebels;

no one’s rich enough to feel guilty

about the poor

or poor enough to reach that breaking point.” (Middle Class Blues, Subject and Objects, The Desire of Roots)

In the above lines, the poet deciphers the underlying regularity of survival that imbibes the guilt of nothingness of a regular man trying to live an ordinary life.

“Until I reached the blind alley of night, and

I slowly uncovered myself

observing shops murdered before they were born,

listening to the dead orchestra of the street.” (Street Life, The Book of Lust, The Desire of Roots)

Similarly, the poet in this poem tries to convey his thoughts and perspective on modernism and the price it has to pay for its sustenance.

Still, Ngangom has his ways of escape from this claustrophobic life. He derives his inspiration from the solace of nature and people who are moving ahead and trying to make ends meet. In the poem, ‘Pastoral’ from ‘The Book of Lust,’ the poet writes:

“…we see our true faces

in the first mirror of dawn.”

By the word ‘mirror,’ Ngangom conveyed the sense of facing your true self in the first mist of dawn – an hour when we witness our unmasked self far away from our pretentious demeanour. Again, in the poem, ‘Prospects of a Winter Morning’ from ‘Subjects and Objects,’ the poet voices the tinge of hope echoing from the core of our soul, which keeps us moving forward despite the loathing helplessness.

The portrayal of the idea of love goes along with the admiration for a muse– for the poet’s unforgettable and melancholic love for a woman who belonged to the mountains. “The Gazelle in Winter” and “Monody” from the “The Book of Lust” celebrate women as lovers, but with different annotations. “The Gazelle in Winter,” on the one hand, focuses on the gradual growth of a woman from her childhood to her adulthood. Whereas “Monody” is the remembrance of a lover from the past.

Beyond love and nature, there resides a society and poet Ngangom has always been a keen observer of the burning down of North-East India in terms of its cultural root and provincialism. The poet weaponises the token of ‘memory’ to raise political consciousness about the past and present of Manipur. We found references to Manipuri folklore, cultural practices and tales of North-Eastern legend in poetries like “Genesis End’’. Robin S. Ngangom also paid tribute to literary geniuses like Desmond, Joseph, Pacha, Guru T. Ladakhi and others in this book.

Ngangom’s subtle style of poetry seamlessly channelises ‘mountain cherry blossoms’ and women’s ‘riverine’ hair with Manipur’s political and social setting. Be it brooding for the forgone love, inferiority of survival, modernisation or death, “The Desire of Roots” is an embrace of the mortal journey of every living entity who seems lost and exhausted in the tired plane of Manipur yet never aspires to uproot themselves from their motherland.

Also, read Skopje by Michele Porsia, translated from the Italian by Brenda Porster, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

Excellent