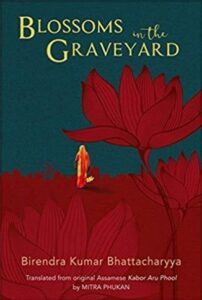

TRANSLATED BY MITRA PHAKUN FROM THE ASSAMESE KABOR ARU PHOOL

REVIEWED BY YASHODHARA GUPTA

‘Nobody asked about the others’ past here. The past was a graveyard.’

And what is a graveyard, but the truest testimony that life has been? That hearts have loved and grieved, that friends have laughed into the morning over promises made and destroyed and made again? What is a graveyard, but a shrine to the memories of the living?

Blossoms in The Graveyard is seeded within the violent birthing pangs of a bloodied Bangladesh. Dreams go to die, and the motherland is devastated. She becomes the vessel for inhuman torture, a depraved self-nourished by the mere memory of what once was. The book forms an archival of sorts, documenting through stories and word-of-mouth, a mosaic of human experiences and historical detail surrounding the injustice shown to the citizens of East Pakistan. It waters the soil of resistance and explores the many dimensions in which protest is necessary.

Islam, here, is the driver of both violence and mercy. It becomes a tool, a weapon, and an olive branch by itself. The Bangladeshi ask themselves if the Pathans are Muslims at all through large expanses of the book. A pious Muslim would never inflict such torment upon another, Mehr says at one point. And yet, as the Pathans lay dying after the guerillas have fired, they are given water because Khoda would have willed it.

Regional disparities are examined through a somewhat polarizing lens, which dips its feet into allotting public spaces for impersonal conversation to men, and private spaces for emotional conversation to women. A dialogue between three men discussing market prices exposes economic inequalities, as they engage in comparing the prices of rice and oil in West and East Pakistan. In contrast, two Muslim Bangladeshi women derive solace from tales in the Puranic tradition, subtly acknowledging that the inner workings of a Bengali household are rooted within the lore of the land, a repertoire that has no religion. This binary becomes even more interesting when the narrative voice switches between the male gaze of ‘Robin Babu’ who explores the personalities of women around him through observations about their bodies, and contemplations of Mehrunissa who worries constantly about the woman’s role in a patriarchal society that refuses to see women beyond their bodies. Throughout the book, Mehr keeps asking which Bangladeshi hero will have her as a bride, given the violence that has been inflicted upon her body. There is not a man in the entire manuscript who can look her in the eye and answer.

Mehr, the protagonist, is praised constantly for the food she cooks. As she struggles initially to come to terms with the guerilla movement, she is shown to often interject within a ‘masculine’ conversation regarding arms and ammunition, to ask about dinner. Interestingly enough, as Mehr comes into her own, this marked distinction becomes hazy. No longer is she bound by the chains of nurture. However, the gender politics step into murky ground as the ‘birangana’ narrative creates a deification of Mehr, with each male figure viewing her as something greater than human. She is posed as a metaphor for the body of Bangladesh herself, her body war-torn, her destiny appropriated by foreign minds. Unfortunately, this reading alludes still to the social understanding of a woman’s body belonging to a larger community beyond her own self.

Birendra Kumar Bhattacharyya captures perfectly the interactions between the personal and the public. Love becomes political, because in times such as this, breath is resistance. When Mehr, distraught by all she has known of life being blown to ruin, asks Habib if he loves her, she is told by her beloved that he will love her more if she joins the guerilla battle. Her acceptance of the gun is a moment steeped in intimacy: her entry into a battle for the motherland thus becomes the most radical declaration of love.

Bhattacharyya is an expert in decoding human behavior. Even in a narrative technique that moves from one story to the next, he finds a way to make each person distinctly motivated by their own beings. As a result, we find the representation of horrible, haunting realities come alive.

We find Malobika, raped in a house that burns her father’s corpse, driven to delirious torment. She lies in wait for her father to come home and find her a bridegroom.

Najma walks into our lives a little later. Her child has been drowned in front of her. Her husband has been mutilated, and her spirit, crucified. The girl who would once giggle into the night about spears and indignance, departs from mortal suffering without a noise.

Brothers rot in blown-up hospitals; aunts are disrobed and raped. Lovers are blinded, grievers wounded- the world is set on fire. And yet, there are stolen moments of joy. There is hope, against all reason; and hope that defies reason. There are sweet afternoons that drive away the ashen skies, if only for a few sacred moments. This is where Bhattacharyya truly shines.

This isn’t a book about survival. In a state of siege, there are no survivors. No victory bells ring out in valor, and no songs are sung of golden bells. This is the story of a birth. It is bloody and painful, it torments and kills; and yet, at the end, there is life. Life that does not yield, that does not bow down or look away in fear. In the end, there is a life that dares to live, that dares to fight.

In the end, there is a woman. A lone woman who stands on her own two feet.

Also, read Regarding Love And Other Poems By Cahit Zarifoğlu, translated from The Turkish by Neil P. Doherty and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments