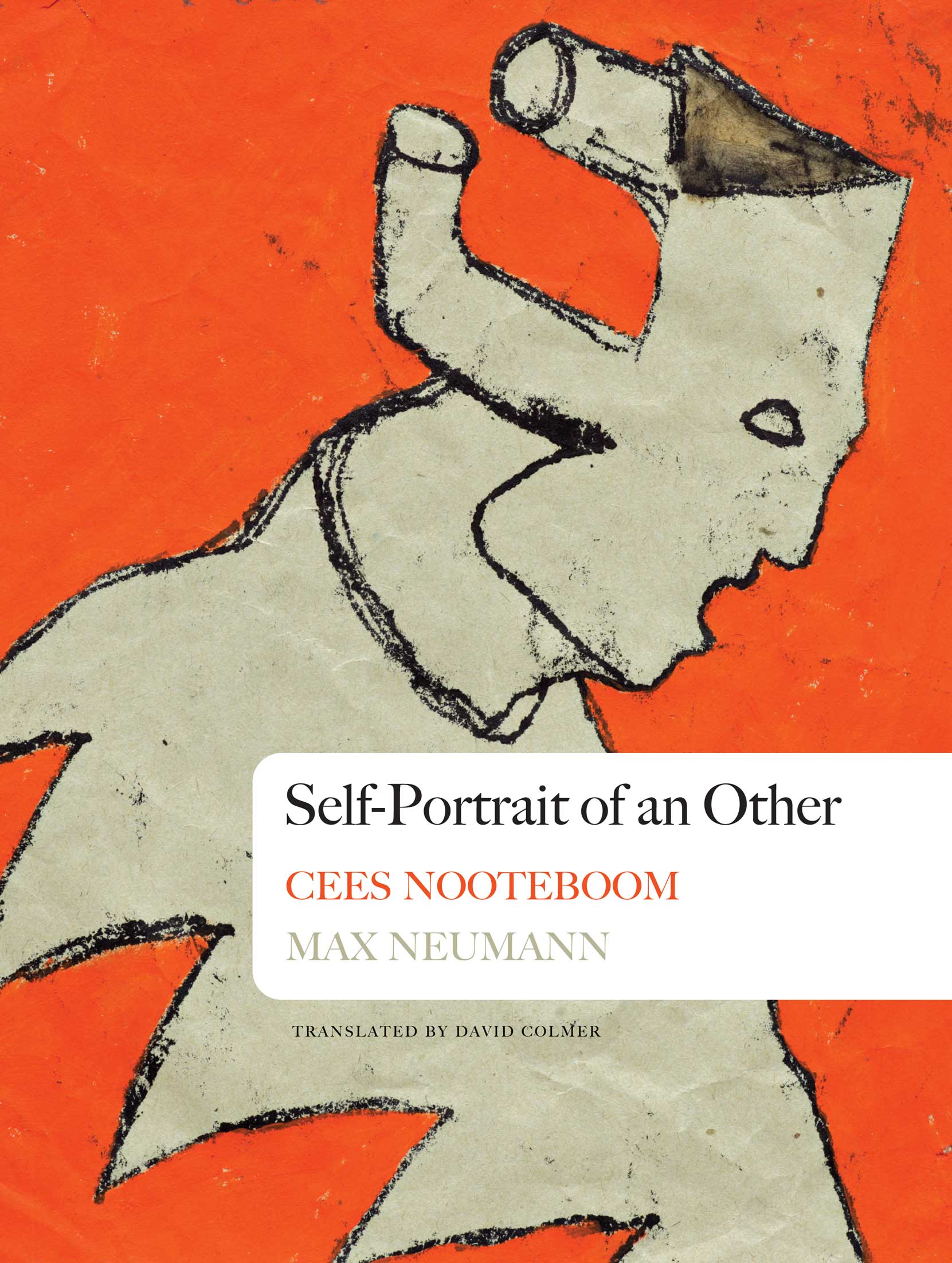

Book Name: Self Portrait Of An Other by Cees Nooteboom and Max Neumann

Translated by David Colmer

40 pages

Seagull Books

Reading Self-Portrait of an Other (2017), a letter-sized book with drawings by Berlin-based artist Max Neumann and prose poems by Dutch novelist Cees Nooteboom, one might wonder which self is calling the other one its ‘other’. Any collaborative venture like this is perennially doomed to this confusion. In the note at the end of the book, Nooteboom, while discussing the project’s development, harps on the issue of this divided authorship:

“… instead of trying to describe his work, I would draw on its atmosphere and my own arsenal of memories, dreams, fantasies, landscapes, stories, and nightmares to write a series of textual images as an echo but unlinked, a mirror, but independent of the pictures he had given me. If we have succeeded, the title cuts both ways.”

One is trying to draw the essence from one text (which in this case, are drawings) and carry it to his/her language. Here, a painting is becoming a prose poem. A writer is responding to someone’s painting through prose poems. If this journey is not the description of the process of “translation”, we do not know what is.

In the most common sense of the term, translation mostly concerns itself with semantics. It is Nooteboom’s poems that needed David Colmer’s active intervention to reach a wider readership, not Max Neumann’s drawings. Painting or sketches have a universal language; we must admit, so do poems—but our primary reaction to any form of visual arts is often visceral; whereas, the language poetry is born into and written in does not have that advantage. Now, we must question ourselves about the nature of the arrangement of the book: if seen separately, do the Max-Neumann drawings feel less adequate?

It is often seen, when poems refer to paintings (or any other artwork), they invariably leave readers a space that encourages them to go against the authorial intent and interact with the reference point. Isn’t this subjective involvement in the affair heavily dependent on language? Will it be wrong to presume that the basic act of interpretation or comprehension makes us resort to language? People connect, disconnect, elucidate, or obfuscate through language itself.

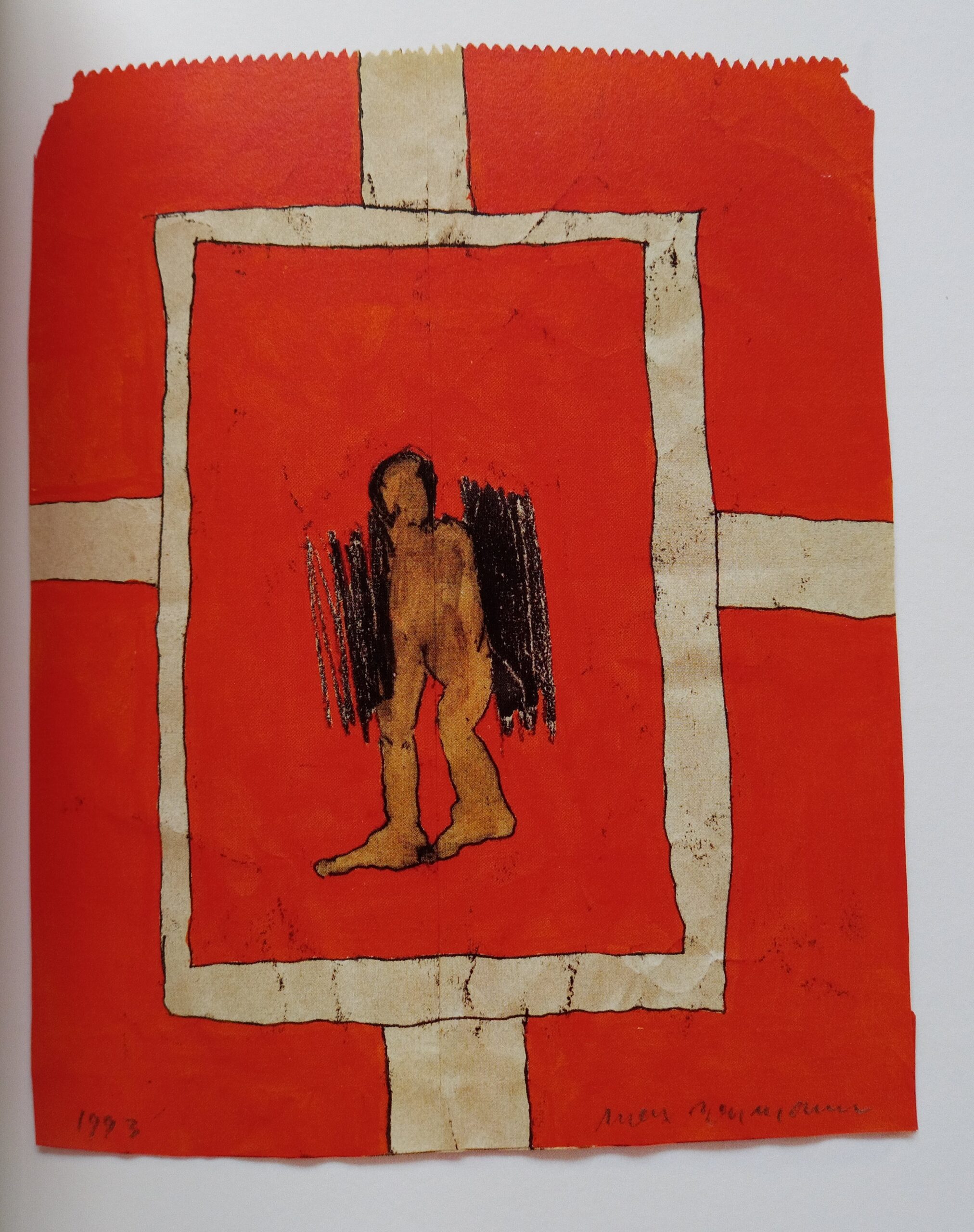

Here, the poem is neither functioning as a caption for the drawing, nor it is utilizing the drawing as a relief to the readers. These two are connected, even after having prominent existences side by side. And, what we are offered here is one of the possibilities in which one brooding mind experiences the drawings this way. Here, the written words acquire an edge over the figures drawn. Here, the written words assume the space of the self, because, we readers are on the same boat as Nooteboom as he makes the journey with us to decode the experiences of the Neumann drawings.

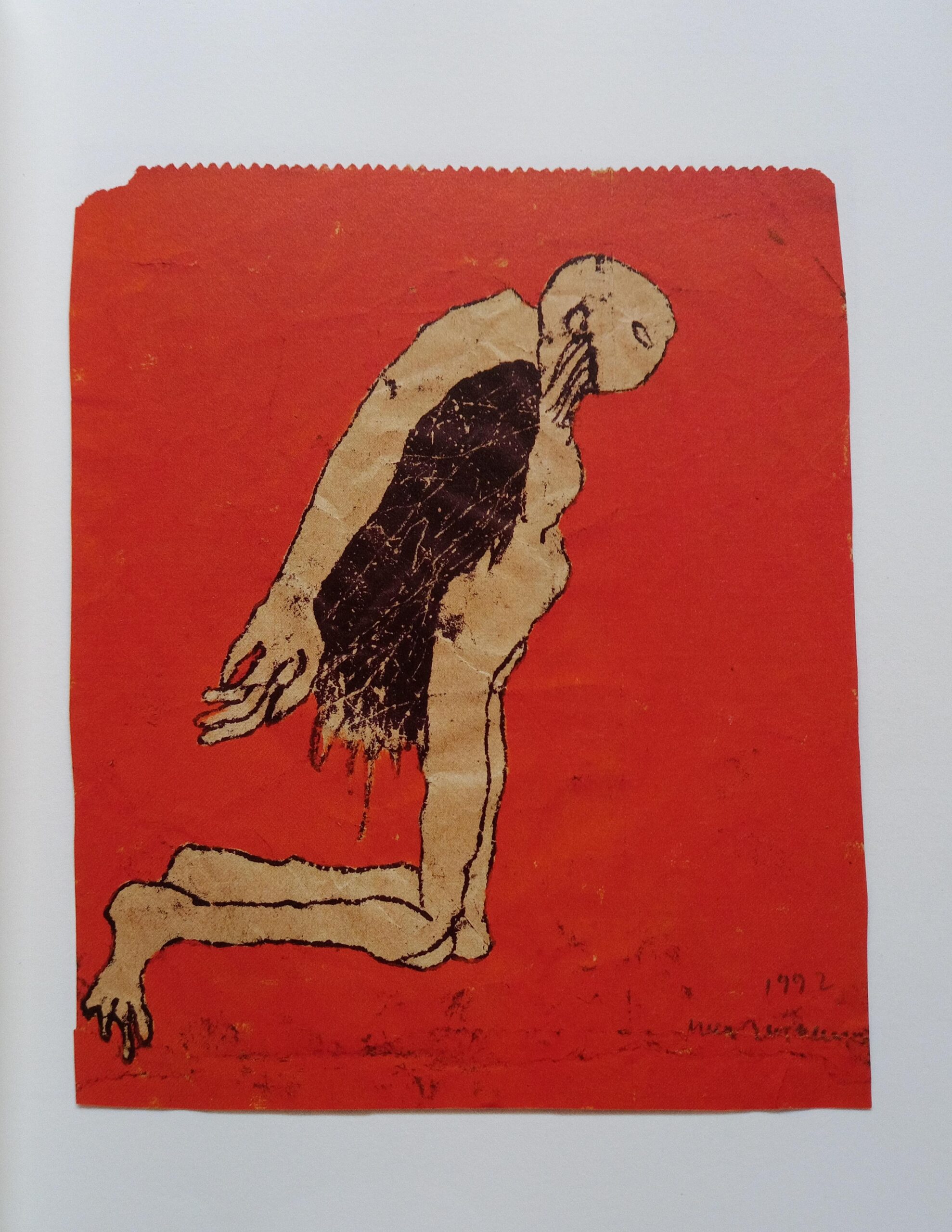

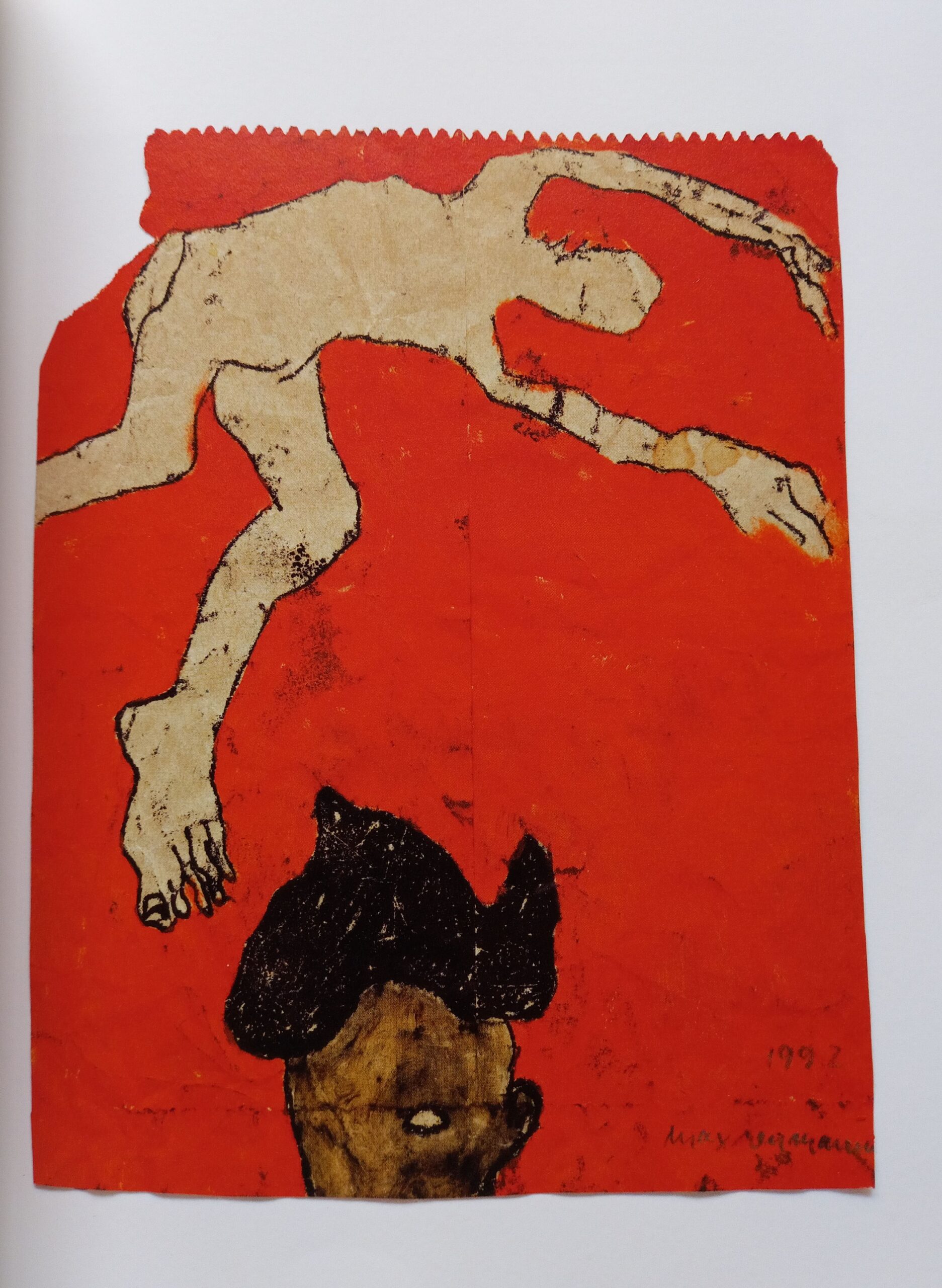

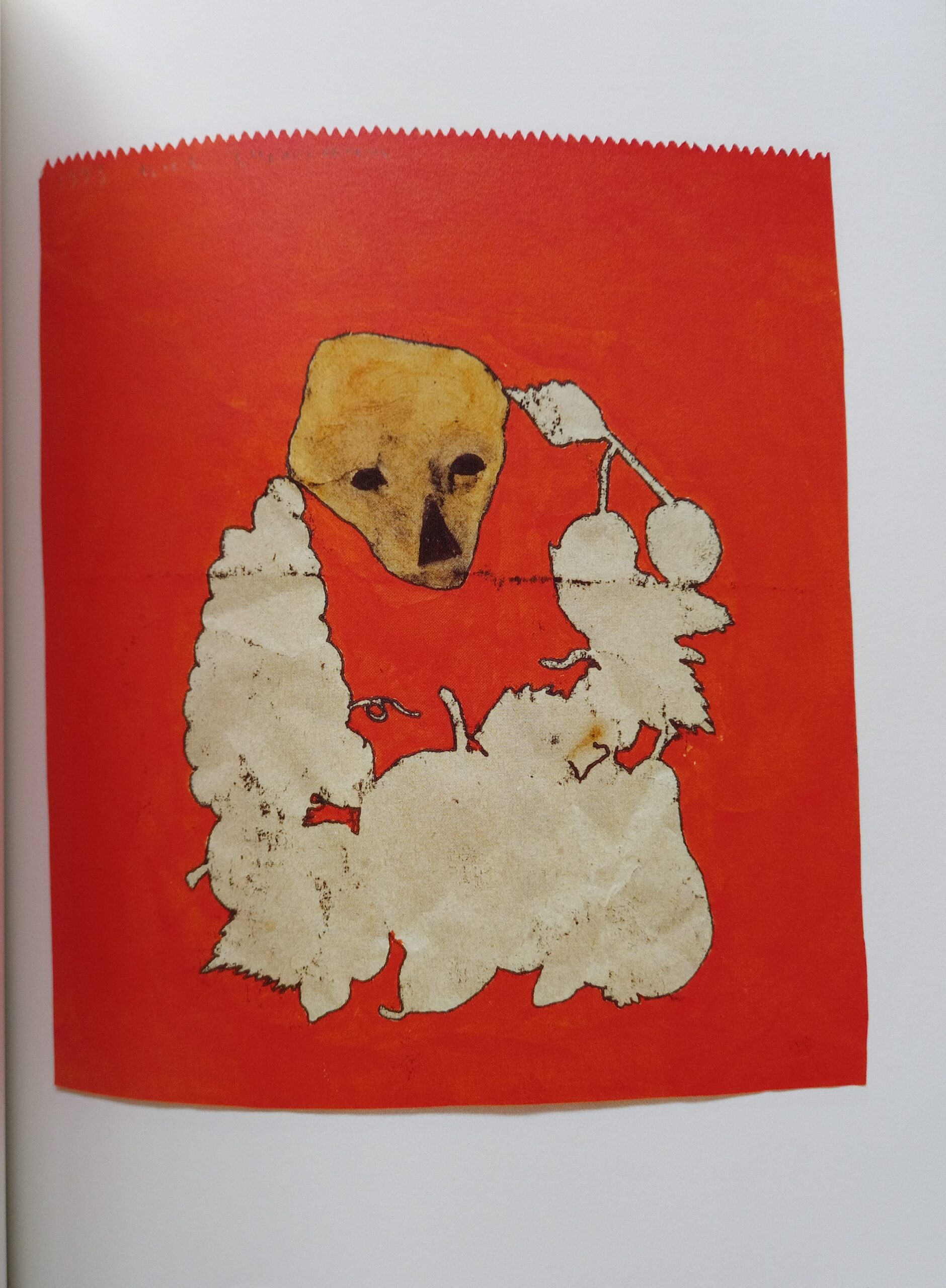

All of the drawings by Neumann printed in the book have a blood-orange background. The figures are faceless. They look wounded, tattered, shattered, and bleeding with excruciating loneliness. Somehow the anonymity makes them the manifestation of the sufferings of our isolated life in modern times. What appears more poignant is that Neumann makes sure their groaning looks are muted.

If there is a central theme traced in all the prose poems by Nooteboom, it is loneliness—the “I” or the subject is fractured.

“When he is alone, crowds become mysterious. Among others, he no longer knows himself. Who are they? Does he recognize his own mask? Sometimes, on trains or pavements overshadowed by skyscrapers, he gives them names. He goes with them, lies in their carnivorous beds, cooks on their filthy stoves, and sleeps with their bodies, possessed by love. Later they visit him in his numbered rooms, their constantly changing faces full of tender lips, their suitcases packed with genitals and teeth. Fragile and mighty, they have left their homes to settle into his protective dreams. Winged Thrones and Powers, rulers of estranged flesh.”

[Section II, companion drawing]

The border between dreams and reality is made blurred through a weightless description of things. It is all about the ‘I’, even the world outside too is centered on it. Now, whether the world exists outside or inside the ‘I’ is a highly contentious issue.

“That morning he had woven himself a mask of green ferns. Now it had turned brittle and dry, poor armour he could no longer hide behind. Like spearheads, the birds dived into the surging waves. He remembered falling faster and faster, the water surrounding his body like writing. He had lain like that for hours. Whether it was true that this was the origin of the island, he couldn’t say. He only recalled the sluggishness once he had stopped falling, the absolution from the violence that had delivered him, the embrace of the sea.”

[section X, companion drawing]

The dissociation of the self results in the desire to hide behind a mask, and then there is the loneliness of a single individual in the sea.

“Now it approached him, the dog that usually walked straight through him. The afternoon burnt like straw, he longed for the river and the soft-voiced boats. He knew that his continued existence was due solely to his addiction to thought, the chains of words he draped over things that remained unnameable despite their names. It had been a long time since anyone had touched him. He couldn’t do it either. His body did not seem to exist. When he searched for it, it was always somewhere else.”

[section XVI, companion drawing]

The book alludes to Arthur Rimbaud’s “I is an other” concept (letter to Paul Demeny, Charleville, 15 May 1871) where, for him, a poet is a seer who arrives at vision by a “long, gigantic, and rational derangement of all the senses”. For Nooteboom, here, the semantic network feels flaccid; consequently, the known things feel less known to him.

The notion of the other, later, expanded itself through various disciplines of which one of the most prominent ones is found in Jean-Paul Sartre‘s account of phenomenology in Gaze. According to Sartre, the relationship with the other is divisive in nature; one either tries to dominate or becomes dominant.

“This time there were two of him. He could tolerate the sounds of the night better on his bird side. In the distance he heard a drum-like thrumming, in the sky he saw rings of fire. In the tall cliff face, there were statues wrapped in cloth, their eyes closed, their stone heads covered with red and ochre mildew. He felt like lying under one of those statues and looking up at it for a long time but his other self raised him with an angry flap of its wings, shooting away from the cliff until it was over the reeds, the field of moving script.”

[section XXVI, companion drawing]

Do these texts, read without the drawings they accompany in the book, look inadequate in their exquisite portrayal of the broken self of a faceless individual? When they describe the world around them, it becomes the description of the internal landscape of the mind. Probably, that is why they feel like dreams, flowing across disparate, disjointed things, unimpeded. Any single broken figure drawn by Neumann haunts us visually, the rough edges along the crack line itself fit perfectly with the one on the companion text by Nooteboom. The poems, as declared by the writer, imbue the drawings with the writer’s dreams, fantasies, stories, and nightmares. If perceived in isolation, the poems and the drawings look independently playing a functional role in presenting a lonely, broken self. But, such is our experience of the book: if we see them together once, there is no unseeing the totality of the broken state of the self. We would never be able to fathom the pain of not having wings on our human bodies until or unless we experience the feeling of having them in our dreams. That awareness, then, will leave us with a permanent sense of insufficiency.

Also, read a Spanish story by Giovanni Figueroa Torres, translated into English by Rajyashree, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments