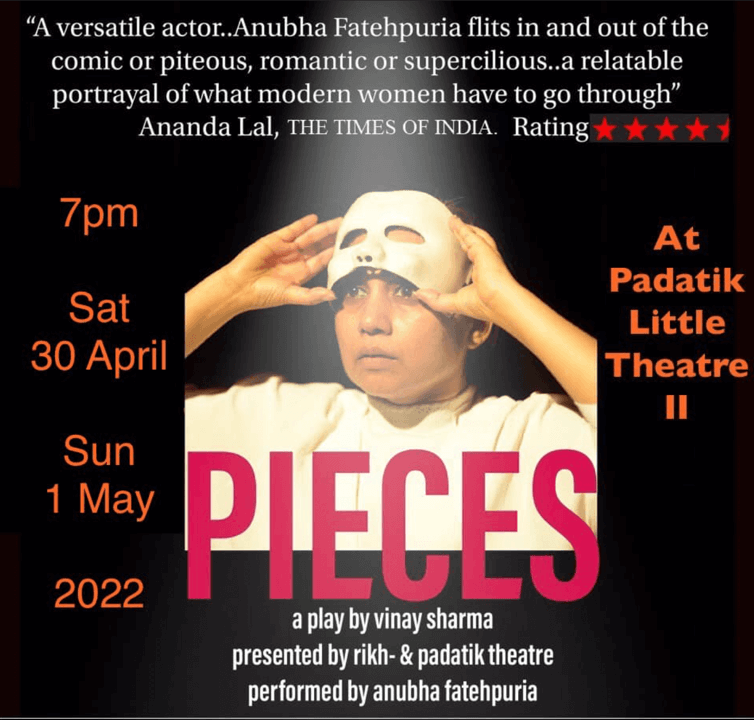

The Brownian motion of reverberating thoughts, zigzagging themselves, wriggled my mind as Anubha Fatepuria took the final bow. The solo act titled Pieces, staged twice on 30th April and 1st May 2022 at Padatik Theatre in Kolkata, had left the audience so captivated that there prevailed a stunned silence before hearty applause found a way back and soaked the small yet intimate performance space.

Directed, designed, and scripted by Vinay Sharma, the performance is an eclectic assemblage of narratives woven with the writings of a slew of authors, mostly playwrights, spanning three centuries—from the 18th to the 20th century. It strings together excerpts from the diverse spatial and temporal realities of authors such as Ferenc Molnar, Anton Chekhov, Laura M. Williams, William Congreve, Guy De Maupassant, Hermann Sudermann, Arthur Schnitzler, Susan Glaspell, Eugene Briex, August Strindberg, and Virginia Woolf.

According to Sharma, who has collated these excerpts into a coherent whole, only about five percent of the script has been written by him. The bits penned by him are mostly (but not always) “connective tissues” between the various scenes that make the performance.

But where do these authors of varied interests and dispositions intersect? In this play, Sharma makes them meet at the confluence of a common thematic subject—the female subject—the women who navigate life, fragmented and fraught with the overbearing patriarchy that penetrates their everyday lives.

It begins with an actress waiting for her show to begin, as she sits on one side of the stage, seemingly conversing with a visitor. As the play progresses, the performer puts on a white mask that covers half her face as she continues essaying different roles that “present vignettes from the lives of various women, young and old, focusing on intimate aspects of their relationships and innermost feelings.”

Within these vignettes, the written word of the aforementioned writers travels to the space of a wholistic performance that is able to rattle the hearts of today’s audiences who are mostly frivolous, restive, and distraught. The words of these writers are not just dislodged from the original contexts of the texts that they are part of but also re-contextualized into the performance space.

These extracts are the pieces that make Pieces. They lie at the heart of the splintered existence of a woman, the myriad roles she must play in her everyday life, signifying the scattered pieces of her being spread across centuries, continents, countries, and communities. The title, therefore, is a double entendre that alludes to the disjointed pieces of women’s existence as well as to the pieces of literary works that hold the repertoire to articulate such an existence.

The experience of watching the play is like gazing into a kaleidoscope—the seemingly unconnected scenes by virtue of their placement, emerge as a variegated mandala of feminine selves, emoted through the haunting yet serene eyes of Fatehpuria. The resultant mixture is a polyphony where each part sustains its individual melody as well as harmonizes with each other!

Having been considered too ‘modern’ for their times, these writers and playwrights have all touched upon the perverse complexities of romance and sexuality. Their far-sightedness finds a place within the experiences of the contemporary cosmopolitan women of the 21st century. Therefore, the peephole of this kaleidoscope is a postmodern one and the patterns thus formed establish continuity and relevance to every woman, each woman, and all women, living in today’s post-modern, post-truth global reality.

All the writers belong to the 19th or 20th century, with the exception of William Congreve, the English playwright of the 18th century. According to Sharma, “The inclusion of Congreve is meant to unsettle the 19th and 20th-century slotting and instead suggest a depictive continuity from an earlier period. The idea was only to place these selected texts, in this sequence, out there for deliberation of the audience and observe or analyze their response and match it with my own—the extreme surprise at how little had changed, going by these extracts!”

What is greatly astonishing is that these extracts are not just timeless experiences of women but also the stories of women that emerge from different spaces of the Western world. While the performance retains the despondent palate of Russian plays through excerpts from Anton Chekov’s one-act plays, it adds a pinch of salt to it by incorporating the grotesque nature of the German plays by Hermann Sudermann and Arthur Schnitzler. The witty and humorous depictions of momentous and pressing situations through the excerpts from the French plays of Guy De Maupassant and Eugene Brieux also find their flavor in the overall recipe of Pieces.

From the onset, the performance journeys to Hungarian playwright Molnar’s one-act play which is a scornful depiction of a woman actor’s ability to convince another woman by means of her immaculate performance off-screen, thus setting the tone of the play. From then on, it sets out to accomplish the task of representing the varied identities of a woman merging into the boundless space of being an actor—as if to say that the ‘act’ of being a woman lies at the heart of a dysphoric performance, a masked existence filled with ironies and satires.

Of all the authors who are excerpted in Pieces, Woolf’s mention startles one a bit. All the others are playwrights. Their texts are written for the purpose of theatrical presentations. Hence, adapting them to the contemporary stage of the 21st century seems to be a plausible thought. But Woolf is a novelist who champions the stream of consciousness. To emote the words of Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse is a task of translation—translation from one mode to another, from the narrative to the dramatic. Woolf’s free-flowing, cerebral character of writing is dramatized into a deeply invigorating monologue with tense background music. I remember watching these lines being performed on stage, as excerpted from Mrs. Dalloway:

“She felt very young; at the same time unspeakably aged. She sliced like a knife through everything; at the same time was outside, looking on. She had a perpetual sense, as she watched the taxi cabs, of being out, out, far out to sea and alone; she always had the feeling that it was very, very dangerous to live even one day.”

And thus emerges the Everywoman figure, the woman who exists beyond all spaces and all times. This Everywoman is someone who recognizes the feminine and the oppressive structures that surround it, the one who realizes that it is indeed “dangerous to live even one day” as long as they are manacled by patriarchy. In a way, it is the universal oppression of the feminine that gives birth to the Everywoman figure, traversing the nebulous and shifting boundaries of womanhood. However, one does have to admit that these experiences of being a woman– the performance of it– lies at the heart of a co-constitutive existence with the male entity which remains shadowed behind the feminine energy of the women characters in the play.

But how does this Everywoman figure born of the excerpted texts of the Western world manifest itself in the Indian context? Sharma said, “Pieces has garnered very emotive responses from both female and male audiences, as it was screened in different cities of India. I’d say yes, it is an Everywoman figure in the Indian context. But it may be too early to assert such a claim. At a later date, once the Hindustani version (tentatively titled Tukde), planned for later this year, reaches many urban and non-urban audiences, we shall discuss such a matter again.”

The patterns of a kaleidoscope are bound by a set of mirrors as is the case with the use of mirrors as part of the play’s set design. A series of variably shaped mirrors form the background of the play, symbolizing the resonance of historical writings and the reflections of women’s lives, operating simultaneously, as they echo back and forth on the stage. This avant-garde treatment of style builds up on the play’s premise explained in the director’s note: “Stories within stories, layers upon layers. On one level—the story of several women, many women. Yet, one more level—the story of an Everywoman figure, perhaps.” At each layer, it makes the particular and the universal converse with each other, making it a self-reflexive exercise for the audience. It breaks the ‘fourth wall’ of theatre by bestowing the liberty of peeling these onion skins upon each member of the audience.

Fatehpuria’s deft and fluid body movements balanced to perfection with the cadence of her voice and grace of her expressions do justice to the play’s claim of non-linearity. The spotlight that hovers over the stage travels through these circular narratives, sometimes settling as a yellow stripe on the eyes of the performer, bringing a spark to the black and white set design and costumes.

Personally, the most striking of the images that I carried home with me was a moment repeated at intervals on one side of the stage. These were moments of transition between intense experiences and monologues. Yet, they were much more. The performer would sit at a resting position on a chair, take off her mask, reach for the water bottle kept at the side table and drink it as the spotlight illuminated her. That resting position was emoted by Fatehpuria with a gaze of pallor, stillness, and deadly calm. Like a poem’s refrain, that gaze haunted the performance as much as it held it together. The image still flashes before my eyes even after weeks have gone by. That gaze of despair summarizes all the violence, the lashes, the engravings, and inscriptions that are historically etched on the being of a woman– even today, even now!

Also, read an interview with Anubha Fatehpuria, taken by Ankita Bose, published in The Antonym.

How Pieces Come Together: In Conversation with Anubha Fatepuria

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

0 Comments