Translated from the Bengali by Bishnupriya Chowdhuri

“I think man’s most treasured possession is memory. It is a kind of fuel that burns and gives you warmth. My memory is like a trunk with many drawers. When I want to be a boy of 15, I open that specific drawer and get back all those images that I saw as a boy living in Kobe. I can smell that air, touch its ground, and I can open my eyes to the greens of those trees. And so, I want to write a book.” — Haruki Murakami

In our part of the world, winter is not another name for death; it is the season of harvest, of birth. One winter, a human child was born in a small town and in the one that followed, was born a pup, inside the dry sewer of a blind lane. Every morning, when the sun turned tomato-colored, the mother would take the child out on the front verandah and coax him to eat his breakfast. And at that time the little dog would come tottering on its tiny legs and lurch below the doorsteps. The pup, a he, was biscuit-brown, touched with black around the corners of his eyes, that appeared like kohl. He had a tiny red tongue and tiny teeth, to nibble at morsels of bread the mother would throw before him. Then his tiny tail would spin, like the rotor blades of a toy helicopter. Watching him eat, the child would finish without fuss his breakfast of milk-soaked bread. And this way the pup soon became his friend.

He was given a name too: Bow. This was the time when the world of sights, sounds, and other senses unfurled moment to moment in the child’s mind in an unbroken verve and was transformed into utterances in his tender voice box. That was how the little dog became Bow. Both were of the same age, though the human child came into the world a year earlier; both equaled in mind. Perhaps Bow was a little older in mind. Spinning his tiny erect tail, Bow turned his kohl-lined eyes at his little human friend and listened to his babble with grave patience. “Bow-wow!” he responded sometimes. “Hmm, exactly! Right you are!”

Their conversation continued through the winter, morning, and evening. During the end of February, a depression formed over the Mediterranean sea. It packed power as it flew over the Indian Ocean, and invaded the land of Bengal from the west like a fierce cavalry charge. Dark nimbus shut the morning sky and, from early afternoon, the town sank under a heavy downpour. Winter, the old hag, delivered the final bite on her way out. The townsfolk slipped under thick quilts and woolens. The roads turned empty before evening. Only the ceaseless patter of rain on asphalt and brick pavings.

The child was snuggled up in the brooding warmth of his mother and the tales of the prince Red-Lotus, Blue-lotus, and the magical birds Byangoma-Byangomi when he heard the sound. Outside the window, somewhere in the evening gully, something whimpered on KNUI KNUI…

“That’s the bugs. When it rains, nocturnal insects rub and dry their wet wings like that.”

But he was not convinced. That was no bug, that was Bow. Bow was calling out. Even though the boy had not heard the creature bark so oddly desperate, he did not make a mistake in identifying its voice amid all the sounds of rain.

Eventually, the elders gave up on his tantrums and the front door was finally opened. He was right. Standing on the second step from the gully to the veranda, was the pup, drenched down to his skin.

Finding his friend on his mother’s lap, the tail which till then was lost between his hind legs sprang up and began to move like the blades of a helicopter. His curled-up body, shivering pitifully as water trickled down his smudged-kohl eyes, stabilized.

Then he was brought inside and wiped dry. They gave him biscuits soaked in a warm drink of Horlicks. The human child saw how Bow licked at it with his pink tongue. Those square biscuits had an oval frame with the face of a man with a wide smile and a long narrow hat. Bow looked up smiling as he ate his biscuit and the child smiled too and the man in the hat in the biscuit chuckled as he melted away.

From that evening, the child belonged to Bow, and Bow to him.

***

In the uncountable scatter of images across the 722 caves of Bhimbetka, there is only one image of a lonely dog. Specialists estimate it to be from the Mesolithic era, painted about fifteen thousand years ago. This means that it belongs to the earlier times of the era (Bhimbetka has images from various stages of the mesolithic times). This image stands somewhat isolated in one corner from the crowd of the mammoths and other two-horned beasts in the lower section of cave number III C-29 in the western hills. However, this isn’t a depiction of any hunt. Right beside the image of the dog, there is an imprint of a palm. Here, arriving in front of these two images, the guides generally fall quiet. In fact, the specialists are yet to reach a consensus about this one.

The Bhimbetka Caves

Mahadeo Gond, the senior guide at Bhimbetka is nearly blind. He taps his way forward with a long stick as he goes on describing each cave. Location and the specifics of the four hundred caves and rock faces of the five hills, filled with illustrations, doodles, and imprints painted for over fifteen-sixteen thousand years, now open for tourists are all inscribed in his memory. One may even consider this entire cave complex as a part of his brain. He leads you on in the smooth, reddish brown alleyways and crannies of his sandstone cerebral cortex. Other than the area open to the public, there are hundreds more such caves on the hills along the river Betwa. Those, replete with the forest herbage and inhabited by only the wild beasts remain almost untouched by the sunlight and humans. The images on them, therefore, have remained far brighter, much more alive. Wandering into the forest with the cattle as a child, Mahadeo Gond had seen oh-so-many of those caves.

As the sun climbs high overhead, the bald sedimentary rock faces heat up and everything begins to tremble in the blazing waves of heat. Mahadeo Gond stoops to light a chuta from his waistband as he stops to rest his back on the cool stonewall under the shadows of the cave.

Eons ago, dense wilderness reigned this land. Tigers, rhinos, mammoths, and numerous other tuskers abounded along with multitudes of other four-legged beasts. One single herd consisted of ten to twenty thousand animals. The forest was impenetrable and it rained volumes. After the long monsoon, attracted by the lush vegetation, the herbivores swarmed into the valley followed by groups of hunter-gatherers. They took shelter in the caves and caverns of these mountains, beside the creeks and waterways. One such group would have about twenty members including adults and children of different ages.

In fact, men were usually outnumbered by females and children. When the monsoon subsided, custard apples ripened. The sweet fruit was relished by the humans and the beasts alike. So there was no dearth of games. The wide grassland lying beyond the Jamunjhiri Nulla, the land where Mahadeo took his cattle to herd, there the men with their rock-head axes and spears would go hunting the large four-legged beasts. Sometimes they would have women too with them but the pregnant and the breastfeeding ones usually stayed back at the caves to forage for fruits and other edibles from nearby. At times they set up traps to catch small games. The hunters returned at the end of the day, sometimes carrying a chaushinga deer or a Neelgai tied to a log; some days, just rats and other serpents.

They chatter around the fire in the darkness. The leader of the group showed how they cornered the monstrous beast, circled it, and finally how he, himself, drove that spear right through his heart. Others nodded and made strange sounds. Fat melted down the carcass and into the flame, crackling and filling out the air with a delicious aroma. The leader had the first claim to the roasted heart. Since the end of the monsoon, he rose to this status. Other than that, he was entitled to the virgin, the one desired by the other males in the group.

The name of the virgin? Let’s say Chhipuaa. She had come of age during this season of the custard apples. She lost her mother to a wild boar attack, that same season. Since then, she stayed close by the cave, daylong. Gathered fruits and roots, painted on the cave walls with a mix of colored stone dust and tree-sap the tales of hunting as they were weaved around the fire. At night Chhipuaa went into the embrace of the leader. Amid the man’s saliva, sweat, and odors of animal blood, she fell asleep, aching. Sometimes, towards the end of the night, the embrace changed to a different one.

One day, right at the crack of dawn, on the other side of the waning fire, she discovered a pair of green eyes, shining bright.

She had been seeing the light for some days now. She has not told anyone about it. At first, she thought that it was probably the stars. The stars descended in the dark of the night over these mushrooms of caves. One day, unlocking the embrace of the man, Chhipuaa stepped out to discover that those green stars were alive. A pair of eyes belonging to a wild dog. Was it motherless too, just like her?

Under the purple light of the stars, she saw that the dog was alone, separated from the herd. Chewing at the bones left in the ash pile. It wasn’t an adult. She had seen/known wild dogs before. These fierce and herding beasts were a threat to all animals. But that was the first time she met one alone.

It came the next day, right at the same time— those green eyes burning with hunger, eager for the leftovers.

Since then, she began to save a portion of food. And every day the animal showed up. One woman and a dog, under the lights of the stars, alive, stared into each other’s eyes. All nights, every night. In that gaze, there was no fear, no jealousy, none.

It could not be found during the day. Where does it go? Chhipuaa wondered and waited for nightfall. Her limbs and her cautious pair of eyes scoured about the pristine earth, collecting flowers and fruits, herbs and roots.

Then the season changed. Winter waned carpeting the forest floor with hues of the fallen leaves. The sky, struck to the naked branches of the trees, became the color of ripened nona fruit. Spring came in jingling the dried leaves. The four-legged herbivores started migrating toward the warm, greens down south.

One day, she painted the lonely dog on the cave wall. And beside it, placing her palms on the rock, spit a mouthful of khoyeer leaves on it. A dog and the stencil of a human palm. None in the group had drawn or seen a painting like this.

Then, all the leaves fell, and a layer of ice formed over the waters of Jamunjhiri, birds went quiet in the forest too. The group of humans packed up and began moving southward following the footprints of the beasts, crossing swaths of bare grasslands for miles. Ice-age was coming to an end. Remnants of icebergs lay scattered. They encountered snowfall and hidden crevasses. They gathered and burnt dried mammoth dung to keep warm. It took an entire cycle of the moon for them to finally reach the southern lands.

Meanwhile, the group had grown. Out of the five that were born, three survived. One, very old, in his thirties, had died too. Besides, the leader of the group, the hunter slipped into a hidden crevasse and broke his femur. They tied him to a sturdy log with rattan creepers and carried him in turns to bring him to the new shelter. He no longer led, though. Chhipuaa now went into another man’s embrace. This one didn’t reek of animal blood. He had the smell of mutha grass.

One day, she found the green lights again, on the other end of the waning fire. Chhipuaa’s body now had accumulated volume, plump padding under her feet. She walked out in quiet, feline steps. And they recognized each other. It lifts its head up, just the way Chhipuaa had drawn it in that cave of Bhimbetka. Without thinking, she reached out to touch the thick fur on its back.

The dog sniffed the unique smell of that hand. The smell made it follow this group for twenty-eight days across the hills and valleys. Chhipuaa felt the warm and wet touch of the tongue on her hands. A wave of electricity ran through the nervous systems of two different species. And this was how a wonder took place in the history of human civilization.

Eons later, a team of archeologists will discover a human male skeleton, fourteen thousand years old, in the dry and arid valley of Araku. Of course, fossils and skeletons much older than this one have been discovered in this subcontinent but what makes this one special is its neck-femur: it carries clear signs of accidental fracture and then of healing naturally. It can be deduced that this group of hunter-gatherers from fourteen thousand years ago, had crossed a significant step in evolution. Because a broken femur leads to complete immobility of any two-legged creature. Among the primitive nomadic hunter-gatherers, it was only too natural to leave behind or kill such a sick or disabled group member.

But then, nowhere— neither in the earth nor in those bones or the stones, shall be found the tale of a pubescent girl and a dog except for that image and the stencil of a palm on the walls of Bhimbetka.

***

The friendship between the foundling pup and the human child, as if reiterated the crucial leap in man’s evolution: taming of the first wild beast by the cave dwellers. Both grow up together. Bow gets a room of his own under the stairs completed with shoe-box, gunny rags, and some pitch-board, he is allotted two meals and milk too, every day.

In the meantime, winter rolls in again. The joker in his tall hats and smile from the circus-biscuit is back too in many posters, flooding the city walls and the lamp posts. “The Circus is here, The Russian Circus.” These days, during mealtime, his mother tells him the stories of a faraway land covered in snow. A country named Russia. The elephants, tigers, bears, lions, and jokers in their motley garments of the circus— they are all from there. The child is told that he will be visiting the circus with Baba and Maa. Will Bow be coming too?

No, he won’t. Only humans are allowed to see the circus. Besides, what if Bow gets scared by those lions and tigers, what if they attack him?

Then one day, the Circus pitched their tent on the mill-ground right outside the city. One can see from the roof, the red-green shafts of lights playing across the evening sky. A tallish man dressed in a pair of black trousers and shirts made rounds of the neighborhood riding on a rickshaw. He pressed his mouth into an amplifier and yelled, “The circus is here, the circus, THE RUSSIAN CIRCUS!” The child rushes to the veranda with Bow. The man in a black dress and hat peeks from the rickshaw and throws a couple of handbills in their direction. But neither he nor Bow can read the handbill that almost looks like a letter from the postman. But both of them know the joker with a smile on his face.

“Keep yourselves ready on Saturday evening, we will be going to the circus,” Baba said to Maa.

These days, roars run through the night air when the rest of the town quiets down, keeping the child awake. How far away is Saturday? He throbs with excitement. The child fails to comprehend and the grown-ups go oblivious to the way in which in childhood, time expands, taking up infinity to roll from one day to another. So they get annoyed and scold him.

Then the Saturday afternoon finally arrives. Sandwiched between his father and mother, the child looks at the tiger, lion, elephant, hippo, and other animals, some of whose images he had seen in the books. And he sees those fascinatingly tall, slim, and agile group of men and girls swinging in the air against the colorful canopy of the circus. Then there were the jokers. Tall, short, thin, and fat— four of them. And they did not look like the ones on the biscuits, the tip of their noses was bright red just like tomatoes.

For quite a few days following the show, he stayed smitten in the dreams of the circus, nibbling at the memory of that Saturday afternoon like a rare piece of foreign chocolate. He went on with his questions as he ate when he was about to go to bed, and right after he woke up, thousands of questions followed that knew no end. How do they fly from the trapeze? They did not seem to have wings. The lion that jumped through the ring o’ fire, how come his mane didn’t go aflame?

When the thin joker spanked the fat one on his bum, did it not hurt? It did, right? Then why was he laughing? What was that red thing on their nose— was it a tomato or a ball?

Following the barrage of questions, began the training for Bow. Placing a low plastic stool in front of him and the bread roller from the kitchen in his hand, off he went like the ringmaster, in his soft childish voice, “Bow, Jum! Jum!”

Bow only wagged its tail like a helicopter and kept at his biscuit. But his training could not be completed. The circus party wrapped up their business and left. And Bow went missing from the evening before.

Strange things have been happening since the arrival of the circus. Tara, the milkmaid reported that her three cows had stopped giving milk leading to scarcity. And the rumor was already in the air of the dogs disappearing from the streets. Whatever doubt people had about their whereabouts, got only affirmed with the roars rising from the circus tent. Besides, that tall man in black and with a gunny sack too was told to be roaming around.

But the child was of course not aware of all these. He was kept out of it consciously by the members of his family. He quit food and water for three days after Bow went missing. He cried even in sleep. He did guess a faint connection though between the circus leaving and Bow. Did Bow leave to join the circus?

Now, there were no shafts of light in the sky. One day, Baba took him to the roof and pointed to the night sky laden with stars— a huge outline of a hunter drawn with glimmering dots in the velvety sky, just like the one in his drawing book. And there, at his foot, stood Bow. “See there,” Baba said, “ He went to the sky and is watching you from up there. I don’t want any more fuss about it.”

But how did he go that far in the sky? The child wondered. Did he learn flying from those beautiful circus people who by some magic, could swing in the air without wings?

***

I could never ask dad. I could not forget Bow too for a long time. When sometimes at midnight our neighborhood fell quiet, I woke up hearing a faint scratching of nails from under the veranda against the brick lane. I hoped for Bow to return. Pain balled up like asphalt inside my chest and before I could realize it, I broke into tears. Maa rubbed my back gently, “Come now, hold it… we don’t want Baba to wake up…” she whispered.

At this time, Maa began to tell me the story of Mowgli. Mowgli, who was about my age, was lost— and grew up with the wild foxes. The story, weaved in her sleepy almost inaudible lull, flashed the strangest of images over my mind like breathes of fog over the glass, they burst through my sleep and took me on their cusp. I plotted, like Mowgli, I too, will go missing one of these days. I shall leave with the neighborhood dogs and go far, far away… all the way to the land of lions, bears, and hippos; to the land of Russia where people can fly without wings. Will I get to see Bow there? Will Bow be back, ever, to me?

Bow did not. The one who did was Kanu, the son of our domestic help, Shanti Masi. He was my age. Shanti Masi cleaned and did the dishes for us. Kanu followed his mother, chewing at the corner of her saree. Shati Masi went about working at five other households, leaving Kanu with us. He ate and played with me. He could fold the lily leaf into a kind of flute and taught me how to suck honey from kolke joba and other flowers. I learned to crack the stony pith of mulberry and eat the tiny seed inside.

In the meantime, I also learned to connect certain stars with an imaginary line and make a bear, lion, and other animals. In the morning, I connected chalk dots on the slate and made alphabets with Maa. Kanu, too, sat in front of me, and Maa handed a piece of chalk to him too. Looking at my letters on the slate, Kanu wrote his on the red concrete floor. This is how he filled up the floor with alphabets, leaving Shanti Masi exasperated as it increased her workload.

One day, my father took us to the ‘Deenabandhu Primary School’. The headmaster had the complexion of a black jamun. Even his palms and the insides of his lips were reddish-purple like the flesh of a jamun. He and my father were acquaintances. “One is your boy, I assume… what about the other one?” He asked.

“He stays with us, take him in too,” said Baba.

The master handed us each a set of chalk and slate, “Now show me some alphabets— “

I finished promptly and looked at Kanu’s slate. He too got them all right, just in reverse. I wanted to correct him but the headmaster rolled his jamun-colored eyes and my father too reprimanded me as if I was about to commit a grave mistake.

The moment marked the beginning of a crucial lesson: Kanu was no longer a friend, he was my competitor. All my classmates at school, were, in truth, all competitors. Their vicious laughter when one failed to answer, the punishments, home assignments, and the red marked exam sheets, all of a sudden turned my carefree days of simple happiness into sad and insufferable ones. I began to miss Bow again. As I walked to school every morning, lugging the schoolbag on my back, I saw how free were those dogs in the neighborhoods. Under the blazing summer sun when I remained fettered under restrictions of all kinds, they just sat at the far end of the gully lolling. Then at night, when all of us went to sleep and the streets emptied, they yapped and worried as they played under the streetlight, chasing their own shadows, barking in unison as if engaged in a competition. In their world, they had no home task, no ear-pinch, no red circles in mathematics copy, no need for an eight’s table or the definition of the present indefinite tense. Every night, before going to bed, I wanted to be one of them, wake up as Mowgli, dreamed of Bow.

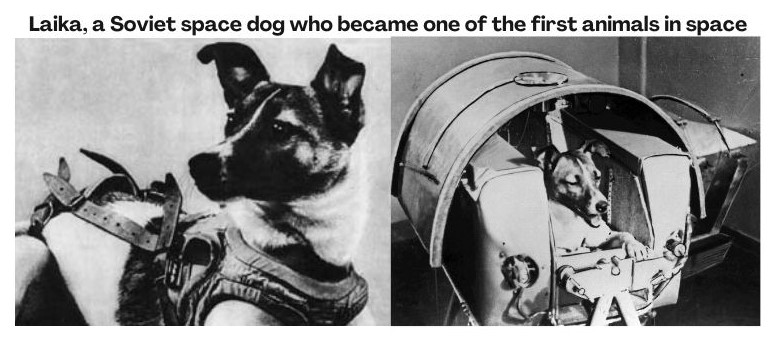

In the middle of all this, Kanu stopped coming too. I was informed that he was sent to study at a boarding school. I grew lonelier. And Baba one day, on his way from the office, got this book about a dog. A smallish one with a pointed nose, a lot like Bow. She was called Laika.

Since my childhood, my father, who appeared aloof and carried a heaviness about him, by some unknown talent, managed to fill out one emptiness in me by conjuring a longing of a new kind. This is how he taught me about the Canis Major, Orion’s dog. Before all the walls and floors of our house could overflow with scribblings, he put me to school. Before my desire of quitting the human communal life for a life with the dogs could get irresistibly strong, he brought me the story of a wonderful cohabitation— a story short yet complete.

Laika was from Russia. I had seen the people from there fly without wings. Like Bow, Laika too was a street dog who flew to the sky. But she did not turn into a constellation, went there on a spaceship. She had to take a long difficult training before the journey. Then she was put inside a huge rocket and sent off to space. She did not come back either. There was no technological arrangement available for bringing her back.

The chief scientist of the project brought Laika home for a day after her months-long training ended before sending her to the space center. The scientist had two sons. They were equally fond of dogs. Laika spent an entire day, from morning till evening with the family. The book was written with the memories of that day. The last day of freedom and fun in Laika’s life.

Each page of the hardbound book was filled with black and white photographs and large letterings in English. Laika playing with a ball in the garden with Misha and Sasha, sons of the scientist. They sat Laika on the dining table and tied a napkin around its neck. Laika, having a circus biscuit with a face of a joker on it, exactly like the ones we had in our country. Laika, sitting among their toys in their study, looking wondrously at the model of the sputnik (on which she will be flying off in just a day); Laika befriending Onitsha, the cat of Misha and Sasha; Laika, watching Tom and Jerry cartoon show on the TV wearing a pair of goggles, ears sticking up like paper-planes; Onitsha on Laika’s back and Laika facing the camera with calm. Misha and Sasha cycle to the forest with Laika in the basket in front. The two brothers had walked up the hill at the back of their house with Laika between them; Laika sitting by herself by the hill with the sun setting; she looking up at the hues of the sinking sun in the sky. Far away, the evening star bloomed.

Each and every photograph of that book got engraved in my memory. The cover had a colored image. A watercolor drawing of the sputnik flying off the star-laden sky, orange flame at its back, and Laika, with a helmet on its head and a smile on its face in the window. The book was named: A Day With Laika.

***

Many years later, I learned the real story of Laika. She was a street dog from Moscow— a mixed-breed, bitch. She was chosen with four other dogs for the scientific experiments as the Soviets prepared for a manned mission to space. Their aim was to find out how the mammals’ physiology was influenced by the zero gravity environment of the spaceship. For this, the five dogs were kept in a laboratory in Moscow and received intense training for months. One of the training consisted of staying put in a specific posture in one small chamber wearing all kinds of tubes and wires on its body for long hours, learning to eat and defecate with the help of machines in the zero gravity space. They were moved gradually to narrower cages and were habituated to eating a jellied supplement. In the end, Laika was chosen. It was decided that she would be the first living thing to board a rocket and head to space and encircle the earth’s orbit. And her bodily responses, her blood pressure, and the beatings of her heart would be monitored from the research center in Moscow. The temperature and oxygen inside the rocket could be controlled via radio signal but after it was done making its rounds and experiments, there was no way to bring the sputnik back to earth undamaged. So, it was decided that after a certain time, Laika will be given her favorite treat but poisoned. She will pass on without pain.

However, the picture book did not have this information. The chief scientist for the mission wanted to give Laika a beautiful day before sending her off on her final journey. The next day, an airplane took her far away from Moscow to the Baikonur Rocket launching center in Kazakhstan. There, numerous electrical wires and markers for various physiological activities were planted on her body through surgery. Then, she was sponged clean with mild alcoholic water, they combed her fur neatly. Before putting her inside the sputnik, all the scientists and engineers of the space center kissed her on the nose.

But the launch did not go as planned. Due to some technological dysfunction, the sputnik overheated long before it could reach its orbit and Laika charred to death within minutes.

This information came to light long after when Soviet Russia got splintered to pieces. About a couple of years before that, the wall of Berlin fell and its debris scattered across the world. I had the chance to witness one of them. On one side, it had graffiti and on the other, a deep gash and a dark brown blotch, probably of blood.

By that time, I knew Kanu was sent to a hotel in Dakshineswar to wait tables. I knew why, on that first day he got all the alphabet reversed. I could never forget Bow. Like Laika, he too went to the land of stars. Trying to remember his face, I see that image in the book A Day With Laika: that flaming tail of the sputnik, and that strange smile on Laika’s face. The smile was exactly like the one on the joker’s face on the circus biscuit.

Note: This translation is an excerpt from Parimal Bhattacharya’s book Nahumer Gram O Onyanyo Museum, published by Ababhash in 2021.

Also, read an Odia fiction about the nagging problem of gender inequality in India, written by Dr. Gourahari Das, translated to English by Snehaprava Das, and published in The Antonym

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

For the month of September, The Antonym will be celebrating Translation Month to mark International Translation Day celebrated on 30th September. A number of competitions, giveaways, podcasts, and more have been lined up for the occasion. Please join The Antonym Global Translators’ Community for updates!

0 Comments