A BOOK REVIEW BY OWSHNIK GHOSH

“Banjara“ is an indigenous ethnic tribe of India. Banjara were historically nomads… Generally known as Gor–Banjara, they are also called Lambadis in Telangana, or Banjaras collectively across India… The word Banjara is derived from the Sanskrit word Vana Chara-wanderer of the jungle.”

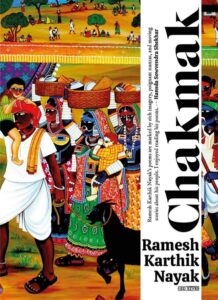

The new poetry collection Chakmak by Ramesh Karthik Nayak, published by Red River brings a new set of images of our country. The less known India. Ramesh is one of the most promising voice from Telengana. He belongs to a Banjara community and represents them through his poetry. He writes both in Telugu and English. Chakmak is his first English poetry book. Though written in English the poems in this collection have a strong essence of the soil of Telengana. The elitist city centric English poetry which the readers are now familiar with, is missing in Ramesh’s poetry. Instead, we can smell the soil from them. We can say that the poet has deconstructed the hegemonic language of the prevailing Indian Anglophone poetry and brought the periphery to the centre. It’s really a path breaking task.

The most striking feature of all these poems is that they resemble the day to day life of Banjara people. For instance the poem Two Worlds portrays the binary between the white and the black world that separates the aboriginals from the urban people. He writes:

Black decides the world of nothing.

White decides the world of everything.

Emptiness walks with us

our shadows drag us back.

Though the power politics is captured by the whites, yet the blacks don’t loose their dreams which keep them going. Their hearts want to fly beyond the clouds but the pure black world wraps them. He sees the black world as a pure one, which again is an alternative discourse. He sees them as puppets within the borders of black and white worlds. He also points out the fake ‘veil of kindness’ which the elites often offer them. Their pretentions trick these people and deprive them of their rights.

In the poem Tree, the poet describes the relationship of the people of his community with mother nature. His grandfather considered trees to be his ancestors. Then the poet claims the history of his community, where all the elements of the earth stand for the evidence. For ages the hegemonic cannons of elite history were written without keeping these tribal people in the scene. They were made to believe that they don’t have any proper history as such. In history books, we read about the kings and their warfares. Do we ever get any reference of the aboriginals who abandoned the place? No one was there to keep any track of their flow of history except themselves. Their history prevailed through folk tales, songs and other cultural practices which went on orally. The alternative history of the subalterns, which was brought up by a group of historians at the end of the last century, slowly encouraged new historians to think the other way round. But yet the hegemony of the history of the ruling class prevails. The poet writes:

I felt

my history is within me.

I should read my history

flowing in my veins.

Another important aspect to be noticed in the poet’s approach is that from the first to the last poems he tries to create an alternative identity of himself and the people of his community. He never allows the reader to feel familiar with the poet. The process of otherization is very important. As human beings we all may be the same, but other than that people will have distinctions in each and every way possible. We have to understand and at the same time respect the unfamiliarity between one people and another, between one community and another. Ramesh’s poetry once again points to this aspect.

The poems Jarer Baati and Our Tanda draw portraits of the Banjara livelihood. In fact in the first poem he invites the readers to their dwelling places (Tandas) and to have chapatis made from white sorghum (Jarer Baati) with them. The invitation is merely just not an invitation of having chapatis, it also opens a door for the outsiders to the world of Banjaras. But at the same time the tone of the poem warns the readers that they don’t get to lead a pleasant comfortable life:

We, the wanderers, move with the wind

on the universal shape of baati

as pollen dust.

The second poem starts with the line:

Our tanda is a bird’s nest

our homes: broken refuges

and our lives are feathers

swirling in the air.

The most safe shelter one can have is one’s home. But when one doesn’t have a permanent home it is an uncertain life. A bird’s nest gets shattered by rain and storms. It has to make its nest again and again. Besides uncertainty there is a stubborn attitude, which prevents one from giving up. A different picture can be seen in the poem Who is God? Here we see these people whose lives are like feathers, floating from one place to another, resists against the government for their lands. In these poems there are different dimensions of their lives. The poet tries to tell the multidimensional tales of their community. Therefore on one hand he points to the bohemian life of Banjaras and on the other hand he shows the loss of traditions and cultures in their community with the flow of time. He also tells about the Banjaras who, after spending centuries in loitering from one place to another have ultimately settled and feel insecure when someone tries to grab their lands. He writes:

We should raise our voices whenever we need to.

Or else we die.

While we come to the end of the book we find that the poet, although have spoken primarily about their community in these poems, it’s not only bound within a particular community, sect or class. Actually the anger that often erupts between these lines is an outcome of oppression and inhumane treatment that the aboriginals and the Dalits have received from the elites for centuries. Therefore when the poets says:

I am not an untouchable

but, better you ask

your own soul if you are

worth touching.

The air you breathe

is dampened

with our blood and sweat.

we can definitely conclude that he is countering the hegemonic power structure with his piercing words. He points out the ignored fact that each and every thing that the socially privileged people use in their day to day life of comfort are drenched with sweat and blood of the people of the working class. These people have the bonding with the mother earth, much stronger than that of the elites. These working people have their feet deeply rooted into the soil but the prevailed ones use these people as their base to climb up in a higher position in the society.

As a reader comes to the end of the book, s/he will be convinced that Ramesh’s voice is indeed a new addition to the world of Indian Literature and he is no doubt a black horse of a long race.

Also, read Love Has its Reasons and Other Poems by Sylvie Kandé translated from the French by Patrick Williamson and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

0 Comments