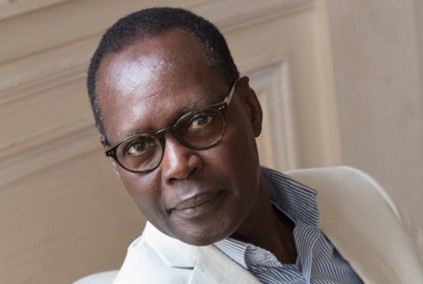

INTERVIEWED BY PATRICK WILLIAMSON

Patrick Williamson: What themes or ideas do you explore in your poetry? How do your personal experiences or beliefs influence your writing?

Nimrod: I only write about the landscape. The weather, the earth and the clouds are my favourite subjects. I tell my life story through them. I may also write about political events and social dramas. Of course, my childhood faith and the ideas and beliefs I was raised in colour some of my poems.

W: How do you approach the art of poetry? Do you follow a specific process or structure when writing a poem?

N: I find it hard to theorise about the art of the poem, because I’m more sensitive to the diversity of ways of writing the poem. I don’t have a preconceived structure; the form of the poem is an adventure.

W: Can you talk about language and word choice in your work? How do you choose which words to use in a poem?

N: A poem is always an adventure in language. Generally, only 5% of the words I use in the first versions of my poems are left in the final versions. I am not one of those poets who reduce the poem via the use of language. My choice of words is dictated by the music of the sentence, because it is the sound that creates the architecture and meaning of the poem.

W: What challenges or obstacles have you faced as a poet?

N: When you come from Chad, there are a lot of challenges and obstacles. Most of the time, the inadequacy of our schooling causes them. That’s why writing for me has been a long-term process of self-training. I set about catching-up, not without pain and doubts, although they were also great incentives.

W: How has your writing evolved over time? Can you mention any specific poems or collections that mark important stages in your development as a poet?

N: My five collections of poems (over almost forty years) are also five stages in my writing. Pierre, poussière (1989) describes the desertification of my country. Passage à l’infini (1999) was dominated by the discovery of the seasons in France. En saison (2004) continued my discovery by broadening this theme and making it resonate with the Chadian climate. Babel, Babylone (2010) returns to the seasons of my country, as does Sur les Berges du Chari, district nord de la beauté (2016). There has always been amplification and renewal. My five collections have taken me across aesthetic boundaries.

W: Are there any poets or poetic works that have mainly influenced your writing style or themes?

N: Charles Baudelaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire, Saint-John Perse, Loránd Gáspár (to name but a few) have shaped my vision, my style and my approach to contemporary poetry. I owe a great deal to their works.

W: You are the editor of Le Manteau & la Lyre, published by Obsidiane. What is your take on current trends in poetry in French-speaking Africa? What are the prospects?

N: M&L is a co-publisher with Obsidiane. M&L is not a collection. Having said that, there are so few trends in French-speaking African poetry – if you exclude spoken word or rap, at least. In French-speaking Africa, these Anglo-Saxon inventions have given rise to performance, ‘open mics’ and spectacle. Even the most media-savvy of these performers rarely rub shoulders with poets.

Poetry, in the traditional sense of the term, has not changed much since the poetry of negritude (1930-1950). The young poets who are trying to invent new paths seem to know nothing about French, English or Latin American literary history. The web and social media have locked them in a ghetto. When it comes to books, how can you create without having a library ranging from Gilgamesh to Philippe Jaccottet? That said, Gabonese writer Stève-Wilifrid Mouguengui has a real style of writing, intimate and open to the landscape. He tells his own story and tells the world’s. The same goes for Olivier Mamgo, a young Chadian I’m publishing this June, with Bleu des saisons. The three of us form a kind of family. But I’m not trying to take all the credit. My choice is limited to books that have touched me.

Also, Read The Only Way Out, By U. K. Kumaran, Translated from The Malayalam by K. M. Ajir Kutty and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

0 Comments