A BOOK REVIEW BY SARBAN BANDYOPADHYAY

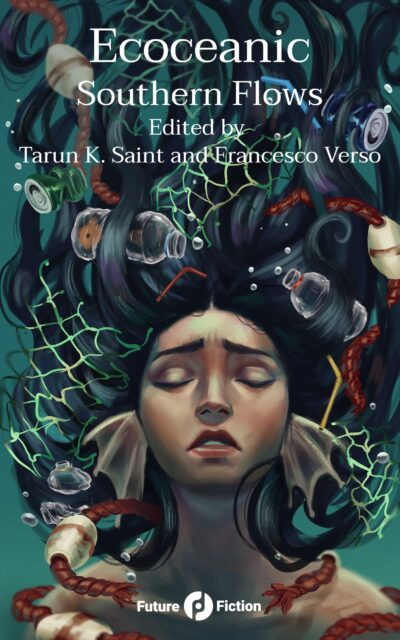

Ecoceanic: Southern Flows is a collection of short stories and a poem with the ocean as their major theme, written by authors from nations from the “global south” which are about to bear the brunt of the ongoing climate change. Edited by Tarun K. Saint and Francesco Verso, it offers fresh perspectives close to lived experiences and presents fresh arguments for emancipatory ideologies as well as challenging the anthropocentrism ubiquitous in mainstream discourse.

All the overwhelming information about climate change, its redressal by humanity perhaps too little too late, the crippling sense of despair and resignation and often the sheer absurdity of it all — all this is crystallized in Kaiser Haq’s inaugural poem ‘The New Frontier.’ Centring around the intensifying activities in the Arctic and the maxim “one’s boon is another’s doom,” it does not hide its misgivings as it gets under the skins of every player at all levels. The poem may be called a philosophical summary of the whole book.

Soham Guha’s ‘Mare Tranqullitatis’ takes the current Indian attitudes regarding climate change to their logical progression perhaps fifty years down the line. Almost no element in this story is fictitious; the defamiliarization happens purely through upscaling which already seems inevitable. The ocean conceals the only surprise, nestled carefully inside one of the shrinking gaps of human knowledge. A nuanced story more pragmatic than speculative, ‘Mare Tranquillitatis’ leaves the reader wondering if it had more to say.

‘Hope at World End’ brings together teleportation and bioengineering to envision a way out of a climatic dystopia. The science is rather vague, but located in a suitably distant future after a Fourth World War. Chinaza Ebere Eziaghighala’s naming of the five interim habitable Domes as Asia, America, Europe, Australia and Nigeria is a smart dig at the sometimes used, ignorant practice of clubbing together the whole continent of Africa as a unit to be juxtaposed with countries from other parts of the world. The solution through bioengineering looks quite tangible from a 21st century perspective. The author’s deft use of the tricky second person narrative is remarkable.

‘The Water Runner’ by Eugen Bacon is a gruesome tale of total corruption in a dried-up hellscape in future Tanzania. Lives are expendable; corpses are commodities; love struggles against an atmosphere of pervasive suspicion. There is the promise of a marine utopia which sounds increasingly false as the story progresses. It ends on a dubious note with love’s defeat almost certain and even a menacing possibility of betrayal. Much like the land, the protagonists too are sucked dry of all their redeeming qualities.

‘Undercurrency’ shows a closer future fraught with the quest for a “middle path,” i.e. after the fashion of the real world it promotes a philosophy of balance. In face of looming environmental danger, Sam Beckbessinger promotes a path of cautious optimism. This optimism spills into its treatment of love as well, which in turn defies boundaries of nation and class. A subtler message is that of real change being effected through people “on the ground” and a first-hand encounter with nature reversing a detached, calculating and somewhat self-centered outlook.

‘I Speak with a Thousand Voices’ by César Santiañez may be the most open-ended story of the collection. Indigenous tradition, the unconscious mind, the individual will — all these are extolled as ways to counter the delusion of power responsible for a dessicated Peruvian landscape. It ends with the hint of an epic battle based on a breakthrough in green technology. The focus is on personal and communal tragedy and the callousness of generations of greed-blinded policymakers.

‘Half-Eaten Cities’ is a poetic reverie of a rising sea engulfing everything but stopping short of the “true wealth” of “them.” The overarching theme of Vajra Chandrasekera’s intense and condensed piece is segregation. The sea is made to understand the dichotomy of “us” and “them” and becomes the great divider of the two. In brilliant flashes of suggestiveness, everything from toxins in the ocean to internalized hegemony among the masses is solidified and satirized. There is no distinction between the public and the government or indeed between the powerless and the powerful, as the elusive “they” with the elusive “true wealth” could be anyone capable of reading this book. The true disaster, it is perhaps hinted, is in the act of segregation we commit by denying our oneness with nature and with each other.

Priya Sarukkai Chhabria’s ‘I Had a Dream’ is a stylised monologue of the ocean itself. She tells the story of the two goddesses of illusion and sleep, and interprets the current dissonance between civilization and nature as the result of humankind’s leaning towards the former. The consequent prayer to the goddess of sleep can be interpreted as an attempt at bringing back balance, or a death wish, or both. This story, together with the preceding, are distinct in their use of language.

‘Shroud and the Moon’ by Thoraiya Dyer breaks new ground in narrative technique. It is a powerful reminder of a few facts, namely: the earth has been through eons of shifting climate patterns; the ocean was the cradle of life; the potential of marine microorganisms is endless; and consciousness may exist in forms widely more diverse than we yet know. This is the story which looks at the crisis of the anthropocene from a cosmic distance, and makes the reader feel the triviality and greatness that are at once to be found in a human being.

The concluding story, ‘The Word for World is Ocean,’ is an eco-utopia by Vandana Singh. While it recalls Ursula K. Le Guin’s story set on the planet Athshe in its title and James Cameron’s Avatar movies in its overall setting, it stands out as a more detailed attack on narrow individualism and an equally detailed celebration of possible harmonious interspecies societies. Both the world and its mythology are masterfully depicted. Le Guin’s influence may be discernible on several levels; but the story suggestively integrates those ideas with the current reality of our planet.

The stories and the inaugural poem of Ecoceanic are conscious efforts to read between the lines of the reality and discourse of climate change. With adequate science and a little fiction, some of them bewail the looming catastrophe while others seek possible ways to escape or overcome it. Chiefly in this search they uphold indigenous wisdom and practices which offer necessary alternatives to the aggressive and disastrous idea of development.

Also, read a literary review of Pieces, written by Ankita Bose, published in The Antonym.

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

0 Comments