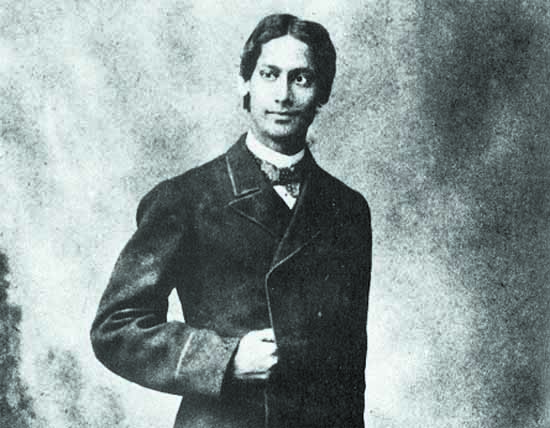

This is the fifth installment in our series on a selection of the journals and correspondences that Rabindranath Tagore had penned during his visits abroad, particularly, in Europe. Below, we have the seventeen-year-old poet’s eloquent description of his first voyage to Europe, undertaken in 1878. Some of the descriptions were reproduced partly in the autobiographical Jeevan Smriti and in the correspondence Europe Probashir Potro (Letters from Europe). The second voyage to Europe, undertaken twelve years after this (1890), is similarly chronicled in Europe Jatrir Diary.

Our first piece in this series was a seriocomic episode from Tagore’s maiden stay in England. As Majid Mahmood (2020) notes, the details of this first Europe journey are rather scarce, except for the poet’s own version. Hence, in chronicling this part, we have no other recourse open other than to refer to Tagore’s letters Europe Probasir Potro, addressed to Jyotirindranath Thakur. According to Tagore’s biographer Prashanta Kumar Pal, the letters were started on the ship and were concluded after reaching Brighton (Mahmood 2020).

Finally, a unique style of the narrator here is the effortless back and forth between the present tense and the past—which we have tried to retain. The following is the translation of the first part of the 3rd letter from Europe Probashir Potro. To read the 1st letter, which was published in two parts: click here to read the first part, and here to read the second part. To read the subsequent second letter: click here.

Letters From Europe— 3rd Letter

Translated from the Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta

Tagore Attends A Fancy Dress Ball

The other day, we went to a Fancy Ball. Ladies and gentlemen had dressed up in a bewildering variety of costumes. Some six or seven hundred beautiful couples jostled for space in a massive hall, brilliantly lit on all sides with gas lights. Bands played all around.

In each of the many rooms, crowds of men and women held hands and danced frenetically. Each room housed seventy to eighty couples, dancing so close to each other that they could fall upon each other.

In another room, champagne flowed in abundance with meat and wine. An overwhelming crowd of people covered every space. In another corner, a lady couldn’t stop dancing, she had been on her feet for hours. One white lady dressed as Snow White, her exquisite beaded attire glittered in the light. Another, disguised as a Moslem lady, wore red puffed pantaloons paired with a silken peshwaz on the top and a headdress of sorts. The ensemble looked rather nice. Over on another side, a woman had dressed up as an Indian lady—donned a saree and a blouse, with a stole on top. I felt she looked much better than how she would in the typical English garment. Yet another lady came dressed as an English maid.

I dressed as a Zamindar from Bengal, wearing a sequined velvet dress and a matching velvet pagri. One gentleman among us came as the talukdar of Oudh, wearing white silk pantaloons, chapkan and jobba, his pagri all dazzling with zariwork, and he had a matching cummerbund. I do not really think that Ayodhya Talukdars actually wear such clothes, but no one was there to question the authenticity of his get-up. Yet another gentleman amongst us dressed as an Afghan General.

Last Tuesday, we attended another ball invitation at a gentleman’s house. The cold weather demands that you wear thick clothing if you are going out in the evening. However, in these evening parties, your clothing had to be of the finest material. The shirt itself has to be pure, flawless white, on which one has to wear a thin front-open vest coat so that a good part of your white shirt-front shows. Then you dangle a white necktie from your neck, and to top it all, a tail coat which is waist-length at the front, but the rear part hangs like a tail at your back. So, I had to ape the English and put the tailcoat on. Then, to complete the ensemble to perfection, all appropriate for the dance party, you have to wear a pair of white gloves, so as not to soil the hands of the lady which you would be holding while dancing. In other places, you have to take off your gloves in order to shake hands with a lady, but the rules for the dance room demand otherwise.

Anyway, we arrived there at half-past nine. The dance was yet to start. The hostess stood at the door to greet and welcome the guests, shaking hands with close acquaintances, and bowing her head to the less familiar. In this British land, the status of the Head of the Family is not of much consequence as far as the dance Invitations go. It matters very little whether the man is present in the dancing hall, or is snoring in his own bedroom. We entered the ballroom, all aglow with a gas light, which however seemed dim against the myriad of resplendent beauties; a festival of loveliness enough to enchant anyone.

On one side of the room, piano, violin, and flutes played… Sofas and recliners were lined up against the walls, the occasional wall-mount mirrors dazzled in the reflection of the gas lights and the fair faces. The dance hall had a wooden floor bereft of carpets and was polished to a slippery smoothness. The more slippery the floor, the better it was for dancing, for the feet can then glide easily without friction.

The balconies around the room had been decorated with plants and floral shrubbery, creating bowers so the young lovers, exhausted from all the dancing could retreat there and carry on with their love talk.

On entering the hall, everyone was handed a gilded plan of the day’s dances. English dance can be of two types—in one, only two people dance together, and in the other, four pairs of dancers and the danseuse form a square facing each other, and holding hands, dance in a variety of rotations. Sometimes there may even be eight pairs instead of four. The first one is called ’round dance’, and the latter is called ‘square dance’.

Before the dance begins, the hostess generally makes introductions between the ladies and the gentlemen. On cue, Miss— and Mr.— bow their heads to each other.

If upon being acquainted with a certain Miss—, one wishes to dance with her, he has to proffer the golden-lettered Dance Program and ask her, “Are you engaged for this number?” If the lady says no, then one must ask, “Then may I have the pleasure of this number with you?” A “Thank You” from the lady would mean that the gentleman has the good fortune of dancing with her. The particular dance number as well as its participants’ names are also entered into the program.

And thus, the Ball ensued. A veritable Merry-go-Round. Imagine some forty/fifty couples in a single room, dancing closely, jostling, and often colliding with another couple. Still, the Merry-go-Round must go on. The band was playing its beat, feet moved to keep to the beat, and the room got warmer. Once the dance ends, the band stops, and the dancer takes his tired fair companion to the dining hall with the table laden with mounds of fruits, desserts, and wine; they might partake of food, or might prefer the bower for a tête-à-tête.

I lack the penchant for mingling with complete strangers, nor can I dance to those items in which I am quite adept, with partners who are perfect strangers. Truth be told, I am not very fond of these dance invitations. I do not mind dancing with close acquaintances. But, just as card players get annoyed if a partner turns out to be inept, the ladies too get dissatisfied with such an inept partner. My companion must have been wishing death upon me all the while we had been dancing. When it ended, her relief could not have been greater than mine.

On entering the hall, I was startled to discover a beauty of dusky complexion from my own country among the hundreds of fair faces. O, what joy! I could not wait to make her acquaintance… It had been ages since I last chanced upon a dusky face. And her face reflected our own Bengali beauties’ characteristic modesty and piety. I have come across these qualities even in English ladies, but this was indescribably different from the latter. Even her hair was done in the Bengali style. I realized that I had become quite tired of seeing white skin and the arrogance of their beauty. After all, English women are an entirely different race, and my mastery of English etiquette was not enough to be able to frankly converse with them. I could not muster the nerve to cross over the cliches.

Translator’s Note

On the later recollection of this first voyage of a seventeen-year-old youth, Tagore regarded his state of mind as one where the fertile land of his personality was replete with thorns—prone to poke at everything that came his way. He felt the correspondences penned during this phase as expressing more audacity, expecting kudos from his readers, rather than something more substantive. To a mature Tagore, on reflection, his own attitude during this time appeared as if to boast of one’s individuality or superiority over the run-of-the-mill average visitor. Looking back at his attitude during this time, the wise poet observed it to be dominated by an urge to set one’s superior individuality apart from the so-called mediocre visitors.

Hence, upon retrospection, Tagore deemed the letters disrespectful toward the countries he had visited. Also for the poet, his younger self who composed the letters seemed naive in his perspective of the world. And so, he never agreed to have these letters published

In spite of all their flaws, however, one justification that Tagore believed, could be offered in favor of Europe Probasir Potro is its language. It was probably the first prose matter in Bengali literature written in the colloquial tongue.

To read earlier episodes of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

To read the next part, which is the English translation of the second part of the above letter, visit the following page of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

Excellent translation that doesn’t feel like a translation! Best wishes!