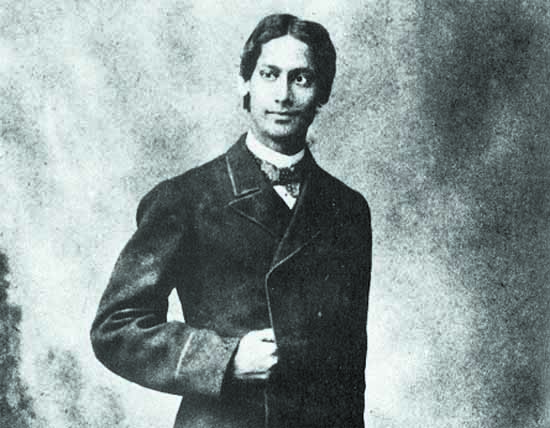

This is the sixth installment in our series on a selection of the journals and correspondences that Rabindranath Tagore had penned during his visits abroad, particularly, in Europe. Below, we have the seventeen-year-old poet’s eloquent description of his first voyage to Europe, undertaken in 1878. Some of the descriptions were reproduced partly in the autobiographical Jeevan Smriti and in the correspondence Europe Probashir Potro (Letters from Europe). The second voyage to Europe, undertaken twelve years after this (1890), is similarly chronicled in Europe Jatrir Diary.

Our first piece in this series was a seriocomic episode from Tagore’s maiden stay in England. As Majid Mahmood (2020) notes, the details of this first Europe journey are rather scarce, except for the poet’s own version. Hence, in chronicling this part, we have no other recourse open other than to refer to Tagore’s letters Europe Probasir Potro, addressed to Jyotirindranath Thakur. According to Tagore’s biographer Prashanta Kumar Pal, the letters were started on the ship and were concluded after reaching Brighton (Mahmood 2020).

Finally, a unique style of the narrator here is the effortless back and forth between the present tense and the past—which we have tried to retain. The following is the translation of the second part of the 3rd letter from Europe Probashir Potro. To read the first part of the third letter: click here. To read the 1st letter, which was published in two parts: click here to read the first part, and here to read the second part. To read the subsequent second letter: click here.

Letters From Europe— 3rd Letter

Translated from the Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta

Tagore Attends A Fancy Dress Ball (Part Two)

At long last, Brighton is blessed with some sunshine. Here, on the days that the sun chooses to step out from behind the curtain of clouds, no one stays home. The walkways and the beaches brim full of people. Even though they do not have an inner wing in the residence as we do, women here seem to keep away from the touch of the sun more than the likes of them in our country.

Here we do not leave bed before eight-thirty in the morning. Waking up at six is a genuine cause of surprise for most. I bathe in cold water immediately after. No, this is not your ‘English Bath’, mind you—I pour the icy cold water right over my head. Food arrives at nine, which is six o’clock by your time. The second meal, indeed the most important one—lunch is at half past one, and another elaborate meal is served at eight in the evening. In between, we are offered afternoon tea, bread, etc. Thus our day is partitioned by the meals we partake in.

It is almost four o’clock and getting dark—reading becomes difficult without a light once it is past four. Here the day starts at nine, as hardly anybody gets up before eight. The daylight snuffs out by four in the evening—it is as if they come here on ten-to-four office duty. By the time you manage to open the lid of your watch, daylight is already on its way out. On the other hand, the night arrives on horseback and seems to leave on foot.

There seems to be not a moment’s respite from the clouds, the incessant downpour and drizzles, the all-pervading murkiness and chill. Unlike here, when it rains in our country, the sound of the pouring rain, the thundering clouds, the lightning, and the tempest—all clamor up to a delightful crescendo! Here, the rain doesn’t pour but lingers on in utter quietude and endless monotony. Outside, on the streets, the white, leafless trees are wet haplessly—rain drips and splatters on my window pane.

Back home, our clouds gather in layers—one upon another; here, the sky spreads out flat, and one can hardly make out the existence of clouds. The entire expanse appears as a dull smudge of colors. People do sometimes discuss occasional rolls of thunder, but evidently, the thunder itself is way too feeble to make its presence known. The sun has become something of a rumor—even if one has the rare fortune of catching sight of it in the morning, one is immediately reminded:

My dear fellow, not so fast!

The good days are not going to last.

Winter is closing in. They say we might get to see snowfall by tomorrow or the day after. The thermometer has registered thirty degrees—which is the freezing point. Frost is showing up here and there. The soil on the road has hardened as all the water in it has frozen. The dew has turned into splinters. In some places, the grass appears as if someone has sprinkled alums all over them—the first sign of snow. Every so often, my limbs start stinging under the intensity of this ungodly chill. It is an ordeal to get out of the quilt in the morning.

Some are unable to help laughing out at our desi attire and some are so astonished to see us that they forget to even laugh. I have lost count of the number of people who have narrowly escaped a serious traffic accident, busy as they were laughing at us.

In Paris, a crowd of schoolboys chased our car. They kept yelling, and we salaamed them. Some of them laughed to our faces, some shouted: “Jack, look at the blackies!”

Translator’s Note

On the later recollection of this first voyage of a seventeen-year-old youth, Tagore regarded his state of mind as one where the fertile land of his personality was replete with thorns—prone to poke at everything that came his way. He felt the correspondences penned during this phase as expressing more audacity, expecting kudos from his readers, rather than something more substantive. To a mature Tagore, on reflection, his own attitude during this time appeared as if to boast of one’s individuality or superiority over the run-of-the-mill average visitor. Looking back at his attitude during this time, the wise poet observed it to be dominated by an urge to set one’s superior individuality apart from the so-called mediocre visitors.

Hence, upon retrospection, Tagore deemed the letters disrespectful toward the countries he had visited. Also for the poet, his younger self who composed the letters seemed naive in his perspective of the world. And so, he never agreed to have these letters published

In spite of all their flaws, however, one justification that Tagore believed, could be offered in favor of Europe Probasir Potro is its language. It was probably the first prose matter in Bengali literature written in the colloquial tongue.

To read earlier episodes of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

Hi there, I’m really enjoying reading these frank reflections (no matter he later thought them naive!) of a seventeen-year-old Rabindranath. I hope the later letters from this series will also be published, looking forward! And thank you 🙂