So what do we call you—A short story writer or a poet? Is it peaceful in there with both of them living together?

The short story writer and the poet complement rather than contradict each other. I have written much on how both genres are very close to each other – siblings – and in prose poetry, they merge. Both aim to produce condensed texts, utilize symbolism, aim at depth, lead to contemplation, and have a special collaborative relationship with their readers, requiring them to co-create. Both are the result of the writer’s individual vision and unique artistic tools, what Frank O’Conner would call “pure art” as he compares the short story to the “applied art” of the novel. O’Connor in his The Lonely Voice also argues that the short story (and I’ll add: the poem) is “the voice of the artist,” unlike the novel which represents “the voice of society.”

I tend to agree in general with those statements. While the novel includes different voices, the detailed and sometime exhaustive exploration of intertwined relations, and represents an artistic form of sociological-anthropological-psychological research, the poem and the short story both represent the artist’s individual, acute, creative response to the world, in a personal sense.

In this respect, the poem and the short story can be said to be “more artistic,” and therefore, more difficult to “consume,” they are rarely “entertaining”, rarely read to pass time, they are both a more difficult read than the novel. The novel details and slowly explains and builds clear relations between its different component, and this is why I think the novel is more commercially successful: it is a relaxed, “smooth” reading; it also builds easier connections with the readers, and requires less effort from them. In contrast, a reader of short fiction or poetry must “work” (using Umberto Eco’s word), or “labor” (using Roland Barthes’ word) to access the text, and therefore becomes a co-creator of that text rather than a mere recipient of it.

Many of my favorite poets (Charles Bukowski, Constantine Cavafy, Campbell McGrath, Ahmad Taha, Yahya Jaber) tend to have a “narrative line” inside their poems, some of which can easily pass as a short story or a piece of flash fiction; on the other hand, the opposite can be said about the work of short story writers like Lydia Davis, Zakaria Tamer, Mohammed Khudayyir, and Ahmad Bouzfour. Some of their stories can pass as poetry. As a practical experiment, I’ve often published the same piece in two different literary journals with minor modifications, the first time as a short story, the second as a poem, and no one could tell the difference, not even me. My award-winning book The Perception of Meaning (Syracuse University Press, 2015) is labelled “flash fiction,” but it can be easily read as a book of poetry, of hybrids, or all of the above.

To me, genre definitions are not important, what is important is how artistic, creative, and “new” the writing is, how it achieves those goals to deserve the tag “literary.” I also think that the future of literary writing lies always in breaking genre boundaries; this is how art develops and expands onto untrodden grounds, and how what we call “avant-garde” now becomes “classical” further on.

Therefore, it not just “in peace” that a short story writer and a poet are cohabiting in my mind, but it is an artistic-literary necessity that brings them together, and pushes them (dialectically) to explore literary grounds beyond them, grounds that are both prose-and-poetry and not-prose-and-not-poetry at the same time.

Were you born to write? When was the first time you wrote? Was it a poem?

I don’t think we’re born anything from the start. The context in which we are born and how that context develops, proceeds, is far more influential than an individual will or a “given” trait. I can say I was forced into becoming a writer, indirectly.

Unlike many fathers who rarely involve themselves in the upbringing of their children, my father was very involved in his children’s activities. He was also a strict man. He would take me to book exhibitions, buy me children’s books and magazines, go with me to the library in the children’s center I was enrolled in during the summer vacation. He’d choose a book each day, and force me to read it in a serious, concentrated way. How would he achieve that? He’d ask me to submit a written summary of it at the end of the day.

While other children played outside, you’d see me siting in the library reading and writing. You’d feel sorry for me, and if you asked me then, I‘d be envious of the other children running around aimlessly, having fun. However, looking at it from this distance, I think those written book summaries, those serious sessions with reading books, were the first seeds of writing.

In fifth grade, I won the all-country reading competition for my age group, and I remember impressing the judging panel with my book summaries, but more importantly, with my notebook of poems. I remember a particular poem about a Jordanian village, Mahes, which I read aloud to them. Yet, this disciplined, ordered world suddenly disintegrated and fell into chaos when my parents were divorced immediately the following year. With this rupture came three other important elements that contributed much to my later writing: freedom, defiance, and anger.

In my teenage years, I became a metal head. I was exposed to the political, social, and existential topics discussed in the lyrics of rock and metal songs, and I started writing lyrics for songs myself. And as my childhood’s disciplined reading and writing faded away into, and reproduced itself in my teenage lyrics, this later stage also faded away into, and reproduced itself during my second and third year in university, when I started to look critically at the world from all respects, socially, politically, economically, existentially. I started writing op-eds in Jordan’s main newspaper al-Ra’i, and in the university’s paper, in addition to short stories and poems which I mainly kept to myself, but dared, on one occasion, to send a story to a national competition for university and community college students, and managed to win its first prize, the one and only prize I ever received locally, as I fell out from any possible recognition later on as I became very critical of the Jordanian regime’s corruption and oppression.

I continued publishing essays in newspapers and magazines from that time onwards, mainly outside Jordan as local media closed itself in my face. But I kept stories and poems to myself, up until 2008, when, upon the persistence of my friends to publish the stories in a book, I showed them to one of the Arab world’s most prominent novelists and literary figures, Son’allah Ibrahim, asking him to unrestrictedly evaluate their literary merit. After all, these were not just newspaper articles, those texts were part of another category altogether – literature, art- and I was reluctant to publish artistic writing that only pretends to be so, or fails its presumptions. Ibrahim’s reply was extremely encouraging. He also wrote an introduction to my first book, which gave me more confidence to go further, which I did.

You can say that the official year in which I accepted myself to be a writer of literature was 2008, but this must have been based on all the precedents I mentioned, a path that provided me with the necessary tools, seriousness, perseverance, and internal liberty.

Tell us a little bit about your soil and roots and people and alleyways? How have they influenced your creative self?

I was born in Amman, the capital of Jordan, in 1975, a time when the city was economically booming and enjoyed its full grace and elegance. My father was also born in Amman, in 1937, and I’m involving him here because his memory of the city, how it evolved, his own relationship with it became my own memory as well, became intertwined with mine, and became the base from which I depart to see the current Amman, its disastrous transformations.

My father would tell me about his relation with Amman’s river, al-Seil (now non-existent), his going up and down staircases to reach his school in Jabal al-Hussein or the family’s house on Jabal al-Lweibdeh or my grandfather’s shop downtown (Amman is built on Jabals, hills), and so on. I also went up and down stairs, moved around in shared taxis and public buses, and used to spend a lot of time downtown, which, as I grew up, became poor and disorganized. So my “post card” memories of the city is derived from these two sources: my own childhood and my father’s.

My coming of age was in the early 1990s, at a time of abrupt change: The Jordanian economy collapsed in 1989, the first Gulf War raged in 1990, and several social and political upheavals took part in those and the following years. Amman began to deteriorate, enlarge, neo-liberalize, and put on the one-aesthetics-fits-all standardized cosmopolitan look – a global phenomenon related to globalized Capitalism now rampant all over the planet.

These deformed the space I existed in, and the transformed the people I walked among. Poverty began to show itself, to become more evident, more present, as quarters that used to be middle-class became impoverished while the corrupt novo-riche strata moved away further and further towards the western side, isolating themselves in well-serviced, well-protected elite neighborhoods. The poor peripheries collapsed in on the inner city from one side, and malformed dreams of cosmopolitanism and consumerist-driven “progress” collapsed in on it from the other side, and from there my awareness of the city and the changes within it became sharper, taking form as a major influence on my work. One clear example is the story “City Nightmares,” a piece that deals with urban and societal transformations, and is part of my book The Monotonous Chaos of Existence, forthcoming in September 2021 from the US publisher Mason Jar Press.

In my stories and poems, you’ll always find references and footmarks of the people and the city, their noises, their smells, and the deformations that resulted from a failure to “modernize” in a postcolonial context, a context in which the “ex-“colonizers are still present, still influential, still intervening and calling the shots, thus shaping (or de-shaping, deforming) societies themselves. One very sharp example of this detail is Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Lybia today: there are “countries” that are –in actuality- open spaces for the struggle of different global and regional powers, directly or via proxies. At the same time, for a “global audience,” the miseries of the people of those areas are just another news item on TV, watched without even thinking about the details: the millions who lost their homes, were displaced, or became refugees; the thousands of cities and villages levelled to the ground; the millions of traumatized children; each incidence having its own, specific story, each with its own, specific complicated web of relations from the past via the present to the future.

This rather dystopic post-colonial “modernity” in the Arab region, with all its effects, whether subtle or extreme, hidden or obvious, lies in the core of my literary endeavor, both in form and subject.

I feel your writing anchors onto the idea of space—the cosmic and the mundane frequently. Is there a reason for that?

That comes from a claustrophobic feeling of being entrapped in a world dominated by human selfishness, indifference, and a false sense of grandness, thus contributing to, or rather causing, the catastrophic situation of our planet today, and the grim situation of our existence upon it thereof.

Cosmology and evolutionary biology have contributed much to the development of this direction in my writing through expanding my vision towards the distant corners of the universe and diverse species of life on our “pale blue dot” as Carl Sagan would put it. We humans are just a mere nothing amongst all that vastness, all that diversity of life and matter, yet we are undertaking the catastrophic role of driving life on Earth (Homo sapiens included) extinct.

I feel a radical change in human perspective is necessary and urgent. The Abrahamic religions teach that humans are the central point of all existence, the reason of creation, while capitalism (in its attempt to drive consumption into further heights) teaches that the individual (and his/her commodity-driven thirst) is the central point of existence, the reason of it all. Those perspectives are deceptive, delusional, and dangerous.

We need to return to perspectives of collectivity (when it comes to our approach to human society), and continuity (when it comes to nature, our planet and its ecosystem). The notion of humans being, or becoming, “masters of nature” put forward by modernity should be forever abandoned for an approach based on modesty and respect.

In my writing, whether prose or poetry, I try to explore subjects related to those themes, opening up questions, and shaking up well-maintained “facts” and entrenched “truths” in the process. Working on the duality/paradox of the cosmic and the mundane is the best angle from which to depart in that direction.

How much of your writing gets inspired by politics? Do you think political awareness is necessary for a writer to attain relevance?

That depends on how you define the word “politics.” I think that everything is political, from global warming to refugees, from wars to famines; from water-shortage problems to the mainstream standards of beauty; from power relations inside families to the power relations between states in our contemporary world. “Everything is in everything” as Joseph Jacotot would put it, therefore, any point you can depart from will lead you to all the other points. That is politics, and that is especially evident and true in our “globalized” world today.

In that sense, every writing is political, even writing that tries hard to evade being political adopts a political position by doing so: it adopts the position of non-engagement, of withdrawal. In a world plagued with massive injustices and grievances, it becomes an oppressor’s privilege to look the other way, not to pay attention, not to care. Writers who take up the same position practically side with the oppressor, align with injustice through silence. This is a political position. Such silence has been brilliantly explored by Sven Lindqvist in his Saharan Journey, as he looks at early 20th century French novelists who chose not to see their country’s colonial atrocities in Africa when they wrote their “romanticized” novels about the continent’s desert.

Another factor: don’t forget that I live in the Arab region, an area ravished by war and intervention and settler colonialism; by corruption and poverty and oppressive regimes; by inequality and discrimination and injustice and, on top of all that, a massive urge for liberation. How can I not be influenced by politics? We drink politics with our everyday water, whether we like it or not.

The issue here is how political influences express themselves in a literary work; how is it possible to rid a literary work of pedagogy, propaganda, and directness; how to transform decisive conclusions into questions; how to utilize form to achieve a creative text. This approach is far from impossible to achieve. While Frantz Fanon wrote The Wretched of the Earth, Aimé Césaire wrote Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, and Varlam Shalamov wrote Kolyma Tales. Politics and literature are not mutually exclusive, far from it, there are many very successful examples to the opposite.

You experiment with forms in your prose often—using visual elements such as daguerreotypes, footnotes etc. I am curious to learn your stance on hybrid forms and if they liberate the text or shrink its possibility—say, how a window opens a view but also fixes a frame by definition…

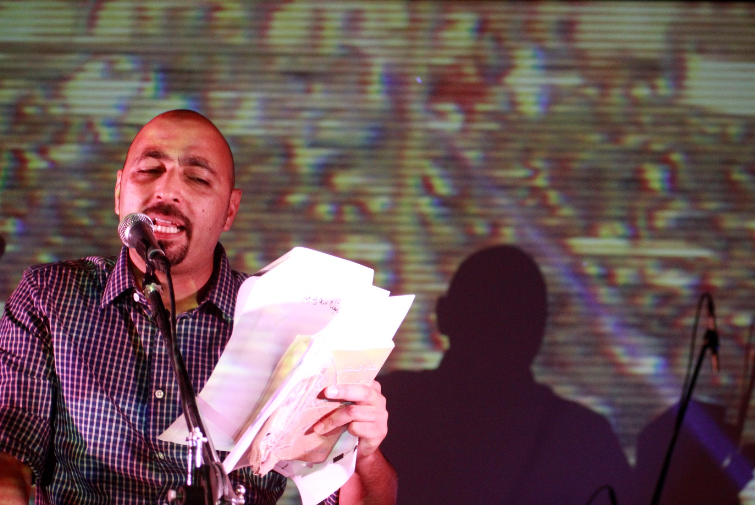

As I said earlier, the future of writing lies in breaking genre borders, trespassing, and using all artistic potentials possible in the art of writing. This approach does not limit itself to the genres of literature, but a writer should also expose oneself and utilize all arts, sciences, and philosophy. In addition to utilizing painting, photography, cinema, and music within my writing, I also employ ideas, concepts and forms derived from physics, cosmology and biology. In addition to that, I collaborate on stage with musicians, hip-hop artists, audiovisual artists, contemporary dancers, and painters, setting up performances that integrate my texts with these arts. This informs and expands the horizons of my writing, and enables me to utilize tools and perspectives that cannot be known to me otherwise. I learn new ways of writing through collaborations.

Within the text itself, as you mentioned in your question, I use “inserts” and footnotes to help the reader become more involved in the process of creation, whether in the form of engaging contexts, or –at many times- contributing to a different reading, or many readings, of the same text. Once you hit the end of the text and read footnotes that appear –uninvited- at the end of the page, you might be tempted to read the piece again, departing from a different angle, or equipped with more exploration tools. I try to give “access keys” to the reader, not answers, and we should not forget that at many times, the footnotes themselves comprise stories or poems on their own accord, adding to the multiple layers of the text a reader has to explore, decipher, and weave.

But, what you mentioned is also correct, footnotes and inserts do tend to fix a specific frame of reference, impose a certain lens, so I’m trying to use them less and less, especially with the internet facilitating the search for unfamiliar information embedded in a text.

If not a writer, what would you be?

A guitarist in a rock band.

Do you feel equally close to your translations as you do to the originals? Do you have a favorite among the languages that your work got translated to? Anyone that felt closer home to your original?

For your first question, the answer is yes and no.

Yes because I have a fairly good command of English, so translations into English involve a lot of collaboration with my literary translators. So far, I have been very lucky to work with very capable, smart, meticulous, and creative translators from Arabic to English. We discuss the many drafts over time in detail, until a result is attained that reflects not just content but also form, context, and structure, in addition to deeper cultural undertones.

No because Arabic is a very moldable language, achieving complex sentence structuring, maximum flow, and comfortable gliding through chronology achievable by a wide set of tenses that can sometimes be superimposed over each other to attain strange configurations like, for example, a “present within the past.” Because of these Arabic language peculiarities, which also include things common with all other languages like words with dual meanings, psychological-historical-social “weight” of certain words or structures that cannot be reproduced in another language, puns, turns of phrase, figures of speech, and so on, something is bound to be lost in translation. But I can also say that the translator’s creativity in finding solutions for those obstacles tend to give me a lot of joy and satisfaction, one derived from the fact that the translated text is an independent text altogether.

I also cannot “feel” many English words internally, deep down, so I cannot assess their effect on the reader, and their specific effect in a sentence or a stanza. An obvious example is cuss words. While I would react viscerally to such words in my own language, similar words in other languages (even if I knew their meaning) will never stir the same internal, deep, psychological reaction. That is why I cannot translate my own work into English, and that is why the translator will have the final say in any disagreement we might have during the translation process over words or phrases.

As for translations into languages other than English, which I have absolutely no knowledge of, I have nothing to say except the great estrangement one feels towards a text that he’s “written” but he can’t decipher.

While the English translations will definitely be the closest thing to the original (for the sole reason that I can fairly assess the end result, give extensive feedback to translators, and so on), I have no way of assessing what translations into other languages are like. In such instances, I usually consult friends who know the language, and if none can be found, I’ll have to trust the work of the translator after assessing their level of experience, their knowledge, their literary abilities, and (maybe most importantly) their care for detail – their obsession with perfectionism.

You haven’t written a novel yet. Do you want to? What would it be about?

I will not be writing a novel in the near future, possibly never. It does not quench my literary-artistic aspirations in a text. I think the mainstream novel is a lesser literary art, closer to a discussion of ideas, characters, relations, societies, and interactions utilizing art as a secondary medium. It is closer to pedagogy: rarely do you finish a novel without a “direction” or an “instruction.”

At the moment, I am more interested in art when writing literature, as I contribute to the discussion of ideas, politics, social relations, through non-fiction, which I also write extensively. My first book in that category will be released next month (February 2021) in Arabic, under the title roughly translated to: (Dys)Functional Polities: The Limits of Politics in the Postcolonial Arab Region.

Many writers in the Arab literary sphere have migrated from the short story and poetry genres into the novel, searching for awards, fame, recognition, acknowledgement, and reach. The more sincere of them claim that they are be able to “say” in a novel what they cannot in a story or a poem. The latter claim is correct. Novelists can (and do) “elaborate,” “explain,” “clarify,” “expand.” I think the novel is a good medium to research, discuss, and expand on a subject, but that takes away from the art, form the literary aspect of writing. I am much more interested in the “literary,” in art.

Choose between: rigorous discipline or waiting for the muse to take you out on a date.

So far I mainly write on impulse, when something is struggling to come out in words it declares itself to me in the form of “mental boiling”: an idea that keeps tossing and turning until the proper first sentence comes out, dragging with it parts or all of the rest in an embryonic format. This is my “first instance” of writing, which I almost always file away, and return to when “the book” ripens, and by “the book” I mean a body of work that represents a specific phase of writing. It is then that I take out all the filed drafts for rigorous and disciplined work to formulate these fragments of impulsive embryonic writing into a mature body of work. Within that process, usually done over a short period of time, pieces take their preliminary shape and form, receive titles, and are, over a longer period of time, edited and reedited until a satisfactory result is attained and published in a book. I rarely publish single pieces in Arabic before their appearance in a book. The book is the context wherein all the pieces of a certain period belong, and I would prefer them to be read in totality within that context.

This feeling of satisfaction is transient. I often revisit, and sometimes rewrite, my work. For example, I have rewritten my first book (entitled: Of Love and Death, first published in 2008), since I am no longer satisfied with how it first appeared.

I sometimes discipline myself to write something, as when I’m commissioned to write a piece on a certain topic or for a certain project. A current example is a project I am working on with a contemporary dancer, slowly taking shape as a series of responses and counter responses, hers in videos of choreographing my poetry, and mine in poetry engaging her dance material. For this, I have to sit, watch her work many times, write down my feelings, impulses, and ideas, and then, formulate those in a poem-text that I send her.

I think that I’m more productive when I work under discipline, and more creative when I work on impulse. There is no magical formula for integrating both, or managing a balance. So let’s just say I’ll leave things as they are!

_

A poem by Hisham Bustani ,translated from the Arabic by Thoraya El-Rayyes –

On the brink of

Two men carry a palm tree downhill to the end of the street.

Where are you taking your mother, you ingrates?

At the end of the street, a dumpster.

The men walk back, side by side.

One talks into his mobile, the other picks his nose.

A jilbab-wearing woman walks along with two girls.

One holds onto the edge of the long, button-down cloak, tripping as she walks but never letting go.

The other: as soon as her mother throws away an empty juice box, she jumps onto it – keeps jumping and jumping. There is an ancient bloodfeud between them.

The box has become part of the street, and she is still jumping.

And the jilbab wearing woman and her stumbling hanger-on have disappeared from the scene.

Many cars drive by.

Some speed up as they turn into the street, letting out screech of tires and roar of engine.

Others are slow.

If I hadn’t been watching I wouldn’t have noticed them pass.

An elegant young man in shiny sunglasses hurries past, glancing at his mobile every three steps. Maybe he is late for a date with her.

IF YOU HAVE WASHING MACHINES, TABLES TAPS IRON PIPES, WATER TANKS, FRIDGES, COUCHES, BATTERIES, FOR SAAAAAAALE.

The small junk truck passes by with a boy hanging out the side, his eyes scanning the neighbourhood windows.

The morning is hot, and the air is heavy, and nothing moves. No one wants to sell their junk and furniture today.

More jilbabed women and small children.

A huge stream of jilbabed women and small children walk up the hill.

At the top of the hill – out of sight – is the mosque charity center.

The sound of lewd laughter.

At high noon, women of the night step out of a car with a Saudi plate and the street trembles from the blows of their sharp, high heels.

The morning call to prayer.

The morning call to prayer again, with a slight difference: “Prayer is better than sleep” it announces.

The midday call to prayer.

The iqama calls out: “Prayer has commenced”.

The entire Eid service from prayer call to culmination.

Young men on horses ride along the street, back and forth.

A flock of sheep amble along swaying to rhythm of the bellwether and “Hshhhshhhh, hshhhhhhh” their shepherd shoos them away from sidewalk trees and neighbourhood gardens.

When his voice doesn’t reach one, a pebble flying out of his hand will.

Is this a city?

A light breeze enters the window and the curtain moves a little.

From behind it, you can see the jilbabed women, as if a factory at the beginning of the street keeps churning them out.

A car selling just sliced watermelons calls out.

A car selling potatoes and green peppers and cauliflower.

The candy floss seller dispenses the squeal of his plastic whistle.

The corn-on-the-cob man yells “CORRRRRRRRRN” drawing it out so that it stretches from the beginning of the street to its end.

It would not fit on this page.

There are ants on the kitchen table. Small blond ants. There is a spider who has woven a web in the corner of the shower. A cockroach appears every now and then in the bathtub but does not survive long, before being battered with a squeegee mop.

I feel a tingle on my body and violently smack it in the hope of killing the insect crawling there – between the hairs – trying to wake me. Maybe it’s just a breeze coming in from the window, tickling the hairs. Maybe my brain is being tickled. But I smack anyway, then the tingle reappears somewhere else. And I smack.

I grind my teeth. I know I do it because my teeth hurt, so I relax my jaw.

I stay that way: on the brink of consciousness, the brink of sleep, the brink of anxiety.

Air does not enter my nostrils. The sounds get louder and intertwine into a chaotic clamor. Tens of disorderly ping pong balls fall, bouncing off the walls of my skull.

It’s time to wake up.

I look at the time first: 11.23am. Then I see them in my room:

the jilbabed women, the children, the corn-on-the-cob seller, the junk truck, the two mother-murdering men with the palm tree, the flock of sheep, the small blond ants, the prostitutes, the speeding cars and those quietly driving by, the worshippers, and the headache.

“Why do you sleep so late?” asks a woman who disappears behind black clothing and continues on her way without waiting for an answer.

“Why do you sleep naked?” asks the small boy hanging out the side of the junk truck.

“What is this strange plaster on your nose?” asks the prostitute.

The ants quietly climb the bed.

I close my eyes and draw in a breath… two breaths. And when I open them, the first thing I see is the time: 12:09pm. They have all left. All of them except the headache. And the noise coming through the window does not stop.

I take a quick shower. I put on my clothes. Four sprays of cologne. As I turn on the ignition, the sound of a rock band comes out of the speakers – Dave Grohl’s loud yell “Who are you?” And I drive off.

The sound of guitars and accordions piles onto the loose mass of noise coming from outside. I raise my head and watch my car pass slowly by, with me behind the wheel wearing sunglasses and banging my head to the rhythm as I disappear behind a street corner.

“Wind me up and watch me spin”

“Watch me spin”

“Watch me spin”

More jilbabed women. More cars. Not the sound of a single bird.

The time? The time is 1:16pm.

I close my eyes.

I see two men carrying a palm tree downhill to the end of the street.

Where are you taking your mother, you ingrates?

This poem was first published in the print journal Modern Poetry in Translation, Issue No. 2, 2017. This is its first appearance online.

Hisham Bustani often experiments with the boundaries of short fiction and prose poetry. Much of his work revolves around issues related to social and political change, particularly the dystopian experience of post-colonial modernity in the Arab world. His work has been described as “bringing a new wave of surrealism to [Arabic] literary culture, which missed the surrealist revolution of the last century,” and it has been said that he “belongs to an angry new Arab generation. Indeed, he is at the forefront of this generation—combining an unbounded modernist literary sensibility with a vision for total change.” Hisham’s fiction and poetry have been translated into many languages, with English-language translations appearing in prestigious journals across the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, including The Kenyon Review, Black Warrior Review, The Georgia Review, The Poetry Review, Modern Poetry in Translation, World Literature Today, and The Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly. His fiction has been collected in The Best Asian Short Stories, The Ordinary Chaos of Being Human: Tales from Many Muslim Worlds, The Radiance of the Short Story: Fiction from Around the Globe, among other anthologies. In 2013, the U.K.-based cultural webzine The Culture Trip listed him as one of Jordan’s top six contemporary writers. His book The Perception of Meaning (Syracuse University Press, 2015) won the University of Arkansas Arabic Translation Award, and his book The Monotonous Chaos of Existence is forthcoming in September 2021 from Mason Jar Press. Hisham is the Arabic fiction editor of the Amherst College-based literary review The Common, and the recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Fellowship for Artists and Writers for 2017.

Thoraya El-Rayyes is a literary translator and political sociologist living between London, England and Amman, Jordan. Her translations of contemporary Arabic literature have appeared in publications including World Literature Today, the Kenyon Review, and Words Without Borders. Thoraya’s work has received awards from the Modern Language Association and the King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Arkansas.

0 Comments