Interviewed by Ankita Bose

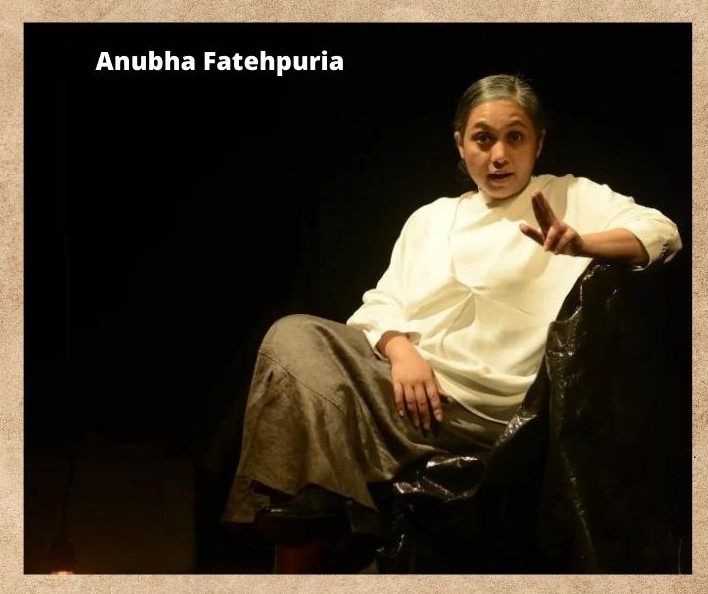

Anubha Fatehpuria is an actor (since 1995) and a practicing architect (since 2001). She is the recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi’s prestigious Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puruskar 2013-14, The Telegraph SHE Awards 2019, and Shyamal Sen Smriti Puraskar 2007. Recently, she received the Best Supporting Actress Award (FOIOA 2022) for her feature film, Ramprasad Ki Tehrvi.

Among the many theater directors that she has worked with, notable names include Habib Tanveer, Shyamanand Jalan, Usha Ganguli, Rajinder Nath, Alyque Padamsee, Wlodzimierz Staniewski (Poland), Suman Mukhopadhyay, Vinay Sharma, Vikram Iyengar, John Britton (UK), Purva Naresh, Abanti Chakroborty, and Tulika Das.

Her on-screen journey is an illustrious one– she has collaborated with directors like Atul Mongia, Anshai Lal, Laxman Utekar, Seema Pahwa, Prasoon Pandey, Aparna Sen, Shoojit Sircar, Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury, Bishnu D. Haldar, Anupam Misra, Amit Sharma, Kamlesh Soni, Vijay Verrmal, Jayant Rohatgi, and Marcel Odenbach (Germany).

Her performances are deeply informed by her engagement with training in Indian classical music, dance, and fine arts. She has done extensive workshop training in Fine Arts under artists like Arup Dad. She has learned Hindustani Classical Vocal under Padmashree Late Smt. Girija Devi and Smt. Mitali Sengupta. She received her training in Bharatnatyam under Smt. Thankamani Kutty & Late Smt. Uma Venkat. Besides Bharatnatyam, she has received basic training in Manipuri Dance under Smt. Preeti Patel and workshop training in Mohiniattam, Kalaripayattu, and Thang-Ta.

Simultaneously, she continues to be a successful architect. She has received the Nagpur University Gold Medal (2001) for her Bachelors in Architecture. She worked as an apprentice with Ar. Balkrishna V Doshi’s organization, SANGATH. She is also a visiting faculty at the Architecture Department at Jadavpur University. Now, she runs her own design studio in association with Ar Richa Bose.

Over the years, her performances have won both critical and popular acclaim, including her current solo act titled Pieces, which was scripted, designed, and directed by Vinay Sharma. She has been an actor with Padatik Theater Kolkata since 2002. Additionally, she holds the position of Director-Programmes for Padatik.

Firstly, tell us a little bit about your journey—how it all began, and when did you take your first step towards being a performer or a theater actor?

Since I was a child, I have been performing on stage alongside my training in Indian classical dance and music. However, my journey with professional theater began in 1995 when I was offered a role in a Hindi play—the play was Badal Sircar’s ‘Pagla Ghoda’ directed by Sheo Kumar Jhunjhunwala, staged at Kolkata.

Later, I studied architecture but the performer in me always wanted to explore theater. Hence, I came back to my home city in order to continue traversing the dual paths of practicing architecture and doing theater, simultaneously.

I have been trained in theater for seven years (2003-2010) under the aegis of the Late Shyamanand Jalan. Since then, I have had the opportunity to work with eminent theater directors and film directors within the country and abroad. I work as a guest actor with various theater groups within and outside Kolkata.

Throughout my journey, I have always given much importance to learning the craft in conjunction with being a performer on-stage and on-screen. I am still learning the craft of acting and theater-making under Vinay Sharma (Kolkata-based actor, director, writer, and scenographer) since 2006.

How do you think your training in the Indian classical art forms helps you as a theater practitioner?

I think that the understanding of riyaaz, a pertinent aspect of Indian classical art forms, is most helpful for me. The exactitude in the sustained repetitions during riyaaz helped me to accept the rehearsal process of a director like Vinay Sharma more easily. The designing and consistency in a given performance are parts of the overall craft of performance-making, and I continue to learn from him as an actor, which requires the understanding, acceptance, and execution of ‘exact repetitions’–among other things–during a prolonged rehearsal process. This may, at times, feel mechanical to actors who believe in performing by relying only on their internal emotional scape or on impulse.

Since you have acted in plays in different languages—Bengali, Hindustani, and English—what part do you think language plays when it comes to the theater? Do you think that each language brings different elements to the fore?

I think language plays a very important role, especially when the theater piece involves spoken text. This is because each language brings its own nuances and suggestions other than what is being said directly in the play-text. Also, each language brings its own phonetics along with it.

The language that an actor takes to be one’s own vis-à-vis a language that is foreign to the actor will also alter the performance in its own, unique way.

Do you have any moments of overlap between architecture and theater? If you do, then how do these overlaps manifest themselves?

Of course, there are many such moments of overlap for me–sometimes these intersections are tangible, at times, intangible.

The tangible overlays for me could take place, let us say for example, between the physical volume we are performing in and the architecture of the set design. The intangible overlays could occur in the form of, let us say, an invisible grid between the performer and the objects on stage or between the several performing bodies on stage, or even between the performer and an audience member at any given moment.

Moreover, many times, elements from the theater make their way into my architectural designs of various spaces.

You have acted on screen too. Your latest TV series titled Mai is streaming on Netflix now. Can you tell us if there is any difference in acting for celluloid as contrasted with acting for theater?

During my long journey of learning and experiencing theater and acting, I think the distance between acting for celluloid vis-à-vis acting for theater lies in the viewing of the performance. For celluloid, the lens manages to reach really close.

The lens, through which any performance is perceived, decides what frame the viewers will see and to which frame the viewers will shift their glance next; also, it is largely a flat-screen experience and the viewers aren’t there with the performer in real-time within the same spatial volume.

For theater, the viewers can exercise a greater degree of choice regarding their lens of viewing. Plus, they are in that same real moment in the same space physically with the performer with no retakes and so the dynamics are completely different. Moreover, the theater allows for the real-time exchange between the performer and audience, especially while performing in an intimate theater like the Padatik Theatre (Kolkata) where you can actually look into the eyes of the audience and perform! Then even theater performed on a thrust stage or in the round and so on – all these bring about their own unique performer-audience relationship of viewing.

As a performer, one needs to keep these factors in mind while crafting one’s performance.

Your performance—Pieces—staged twice on April 30 and May 1, 2022, at Padatik, mainly focused on women’s voices and how historically women have had to playact in their lives. As a woman who is also an actor, do you agree with such a notion?

Yes, I definitely do. I feel that we, as women, are constantly playacting, or rather, I would say role-playing in myriad realms of life. Here, I must mention that role-playing doesn’t necessarily mean being false or pretentious; it is just how one negotiates with life.

Pieces talks about an ‘Everywoman figure’ that emerges as one watches the play. Do you believe that such a homogenized category exists—a space where the sole identity of being a woman is primary—beyond the intersections of the other identity markers like class, caste, race, religion, etc.?

I most certainly think so. That is one of the primary thematic premises of this play; it is what makes it universal. It dwells on the concept of an Everywoman figure who could be existing on any square foot on planet Earth.

Do you think that the English language acts as a barrier in making the play relevant for the audience in India? If so, then how do you think that can be bridged?

In India, performances in English will always have a limited audience. That is why, we have plans to do the play Pieces in Hindustani, tentatively titled Tukde.

However, these days, we can also use technology to make closed-captioning possible for live performances. This can help bridge the language barriers, especially in a multilingual country like India.

Since Pieces deals with women, do you think anything has changed in how women are perceived and depicted in Indian theater today?

Yes, a lot has changed. On-stage and backstage. In stories and in rehearsal rooms.

Though you will still find the classics being performed, and correctly so, which present women’s lives from what we would like to think is of the past; but unfortunately, is very much of now and here, and that is also what a play like Pieces makes you realize. But alongside, there are a lot of new play-texts being written by contemporary and senior playwrights and by some women playwrights who are my contemporary or even younger– and for sure we hear voices of women where they are being perceived and depicted in ways other than from those of the earlier years. Having said that, again, human stories are largely universal and so are women’s… how different we as women can be off-stage in our real personas and how we choose to change our ways of living and play our various roles in reality, are the stories and female characters we will see on stage… so change, equally importantly, needs to happen off-stage simultaneously.

Also, read a literary review of Pieces, written by Ankita Bose, published in The Antonym.

A Kaleidoscope of Women Narratives: Pieces at Padatik Theatre— Ankita Bose

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

0 Comments