KRISHNA GOPAL MALLICK’S ENTERING THE MAZE— A RARE INDULGENT VOICE IN THE GENRE OF QUEER FICTION

REVIEWED BY SUCHETONA PAUL

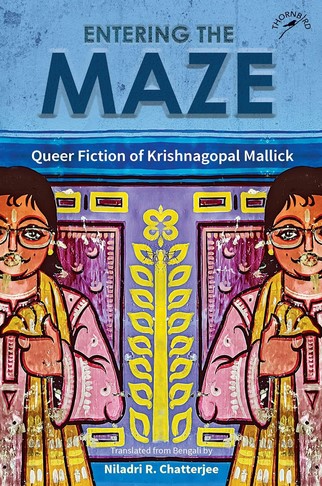

When I finished reading Krishnagopal Mallick’s Entering the Maze, a collection of queer fiction translated by Niladri R. Chatterjee, I wanted to discover the author beyond the confines of this fictional work. Even though the translator, Niladri Chatterjee, has penned an introduction that exhaustively includes the author’s biography, and his literary career, especially a commentary that meticulously discusses his unusual choice of subject matter and writing style, I assumed, in vain, of course, that there must be something else left out, his other works, that have not been translated yet perhaps!?

And as the search was unfruitful, at least in the digital space, I wondered as I held this book, how queer it is that I could not find anything about the author beyond this book. How queer it was that the search results that the internet offers are none but related to this book- a series of critical reviews lauding the little-known queer fiction writer in India. Then, I thought to myself how in the digital era, the identity of the author Krishna Gopal Mallick, has merged with this translated work after all, urging us to recognize his voice through his fiction.

To my great dismay, when I looked for the author’s name in the contents of a book titled Same-sex Love in India- Readings from Literature and History by Ruth Vanita and Saleem Kidwai, no trace of Mallick was found in that long list. On top of that, the very opening statement of the preface like a disclaimer discouraged me further –

This book traces the history of ideas in Indian written traditions about love between women and love between men who are not biologically related. A primary and passionate attachment between two persons, even between a man and a woman, may or may not be acted upon sexually. For this reason our title focuses on love, not sex. (xiii)

And it dawned upon me that, the comprehensive book although dedicated to mapping the history of queer writings of India from the ancient period in history; would fall short to contain the fierce expression of Mallick’s homosexual desire in a fictional narrative.

And then something strange also happened. In a faraway corner of my reading experience, my knowledge of eccentric writers and their celebration of deviations from the norm, I was reminded of Oscar Wilde. As much as I am aware of the incongruity of such comparison, I could only think about how Wilde’s homoerotic desire often disguised, has a celebratory note. And if I cite another similarity after all, it would be the fact that both of them led a heteronormative life, married with children. Sans the tragedy in Wilde’s life, the note of decadence and hedonism, bold confession of the individual’s pleasure-seeking motto in the Picture of Dorian Gray are the converging points I would connect these two authors with. But the similarities will end here precisely because Mallick’s uninhibited expression and exploration of pleasure is a far cry from Wilde’s suggestion of homoeroticism.

Krishnagopal Mallick, a Presidency college graduate, worked as the sub-editor of The Statesman from 1963 to 1967. Under the pseudonym of ‘Nirmalendu De’, he published a handful of prose and poetry. In the introductory note, Niladri R. Chatterjee observes – “What makes him stand out in the midst of all the other Bengali writers, past and present, is the unabashed expression of his homosexuality.” (8). He has persistently used the term “homosexuality”, repudiated the shame and guilt associated with the taboo of sexual pleasure. Nowhere did he express apprehension towards revealing his desire, nor did his identity as a married man ever come in conflict with his inclination towards homoerotic pleasure. The single most remarkable aspect of this collection and this trailblazing author is that the stories begin with a rejection of the taboo around homosexuality. The matter-of-fact voice of the author maps the tumultuous passion, and occasional unease but primarily unalloyed thrill of exploration.

Mallick’s ingenuity lies also in his introduction of an author-surrogate for his fictional narratives. Krishnagopal Mallick self-consciously employs his name and shares a few of his biographical details with the protagonists presented in three separate literary pieces of this collection. And yet this simple gesture, coupled with his candid depiction of his homoerotic desire in an uninhibited manner beguiles us sometimes. The author-surrogate also has keen eyes towards the evolution of his city. The narrator’s voice takes the readers on a tour and like a flaneur delivers detailed commentaries about the nooks and corners of the city. All the fictions revolve around the heart of the city, widely known as College Street, including College Square and nearby places around it. The short story “The Difficult Path” begins with the sentence “College Square is mine all my life…” (33). While the young protagonist from the novella “Entering the Maze” occasionally makes his exploratory trips beyond this place, the vibrant setting predominantly remains the same. The metaphorical maze referred in the title is as much the literal setting of central Kolkata, full of baffling lanes bylanes that define the protagonist’s journey to adulthood.

The collection of fiction makes no attempt towards presenting a value judgement of homoerotic desire or homosexual practice per se. In Mallick’s fictional milieu homoerotic desire is understood less as a deviation from the norm but more as a commonplace scenario, assumed to be recognized by everyone, especially his readers. The fictional realm is devoid of any trace of disapproval and therefore any conflict. Consequently, unlike many celebrated queer novels, Mallick’s fictions are not embroiled in the ideological battle of questioning the heteronormative convention. Instead he reveals regarding the novella “Entering the Maze” that his authorial purpose lies in conferring homosexuality “a dignified position in Bengali literature” (14). In the story “The Difficult Path” he mentions how the focus of his subject matter is the vigorous expression of homoeroticism, “…homosexuality is the one and only driving force of my life…” (37). This is particularly relevant in the two short stories “The Difficult Path” and “The Senior Citizen”. Both of the short stories underline the vulnerability of the author-surrogate – the frailty of old age, the perplexity and the possible threat of being victimized- all of which result from his instinctive homoeroticism.

In the first story the protagonist finds himself in the mayhem of the north Kolkata streets at night. He ventures into accompanying a young boy, who has supposedly lost his way. Although the narrator refers to himself as “a mere sheep” and “a drooling idiot” at the mercy of a young boy, he cannot deny his interest in the tender-looking young boy. At the request of the adolescent boy to escort him to Sealdah, he covers a great length of Calcutta – Harrison Road, Amherst Street, and Mirzapur. The young boy changes his desired destination whimsically, asking him to accompany him a little farther. The protagonist at the age of fifty-nine appears to be less adventurous but more cautious about the boy’s inclination. He is rather plagued by the disturbing thought of probable robbery, or even murder as the young lad takes him to places. Similarly in the story “The Senior Citizen”, the voice of the author-surrogate unflinchingly reveals his crude passion, his debauched practice of getting into public transport to steal moments of perverse pleasure. This story too ends with a threat of being exposed and victimized.

His novella “Entering the Maze”, a bildungsroman traces the protagonist’s transition from boyhood to the threshold of adulthood. The novella, written in the format of a diary, that includes occasional excerpts of the young protagonist – Gopal’s attempt at writing fiction, records his aspirations, and his curious discovery of the world around him. It captures a unique phase of his journey that traces his physical as well as psychological growth – “I am going on fifteen. My body is losing its chubbiness and I am starting to look fit and tall” (119). It is bound to evoke a sense of nostalgia as the protagonist meticulously depicts his daily routine, the lazy afternoons of summer vacations, his hobby of collecting stamps, and his little adventures of sneaking out from home to explore places near and far. The rose-tinted view of an adolescent zestfully looking forward to a life as a grown-up is well-balanced with the reminders of harsh life beyond his familiar circle, especially in post-partitioned India. His stark memories of the violent communal riots in the streets of Kolkata or his reference to the political disintegration of the country indicate that the novella is very much a testimony of the time, as Mallick himself asserted “Maybe this novel is not even a novel; more of a history or biography or a document of my teenage years…” (14). The protagonist in the novella observes –

“But where is Farid? He was my dear friend in the fourth standard. But he has not come to school since the riots. I don’t know what’s happened to him: maybe he has gone to Pakistan, maybe he has been butchered.” (106)

The protagonist nonchalantly records his various sexual encounters, from playful curiosity to unwilling participation with adults. It is however his love for the classmate Manoj that brought him close to a harmonious understanding of his own self. Manoj’s confession of love to Gopal is plain and direct, yet evocative of his fiery passion -“Take me, Gopal, take me! Make me your own, take everything that’s mine” (172). The narrator wonders in retrospect – “Was that the day I crossed the threshold of adolescence and stepped into adulthood?” (173).

Mallick’s novelty lies in his unadorned style of representing some of the detestable characters in fictional terrain and withholding any attempt to make them appear likeable or acceptable in the normative society. Although the author-surrogate blatantly fails to exercise politically correct behaviour that extolls the virtue of consent, he never attempts to draw our sympathy or screen the repulsive habits either. He made no effort to categorize the sexual encounters that can be accurately termed as sexual harassment, even pedophilic in nature. He is aware of the vulgarity that his characters exhibit, he merely presents them like a dutiful, scrupulous news reporter, who isn’t much bothered about aestheticism but fulfils his task of illustrating what he has witnessed.

Also, Read Book Excerpt from Memoirs and Letters—Rabindranath Tagore, Translated from The Bengali by Manjira Dasgupta and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments