LETTERS FROM EUROPE— 5th LETTER

TRANSLATED FROM THE BENGALI BY MANJIRA DASGUPTA

INGO- BONGOS

What strikes as new to a Bengali’s eyes when he first lands in Britain? How do they feel at first when mingling with British Society? I shall withhold sharing my own experiences on this, as I don’t have the right to pass judgment on such things as yet. I have been brought to England by people who have lived abroad for a long time, and they are also my shelter here. I got to learn a lot about England from them even before I came here, so very little struck me as new when I eventually arrived. I did not have to stumble at every step to pick up the etiquette when mingling with people here. So, I shall not write anything about my own experiences now. Rather, I shall recount what other Bengali newcomers have narrated.

So, they board the ship to England. Now, there are many British servants for the passengers, and they cause the first confusion. Many of our first timers would address them as “Sir”, and would feel hesitant to ask for any errands from them. They would live in a constant state of hesitation which was spurred not just from fear, but a sense of intimidation too — always dreading to appear graceless in whatever they wanted to accomplish.

Aboard the ship, it is not often that they get to mingle with the British. The Huzoor Dharmavatars spare the Native Indians a lowly glance if at all and walk away. At times, however, one does chance upon one or two true British Gentlemen, who, on finding you lonely, will make an effort to exchange courtesy and to make acquaintances with you. They are the genuine, hailing from upper-class, noble families. But, the “John”-s, “Jones-s- “Thomas-es” that throng the lanes and alleys of India scare the wits out of the localities they set foot upon. People flee the streets along which they ride on horseback, whip in hand (which may not be for the horse only). A single nod from them has the power to rock the throne of some Indian Rajah or the other. Is it then strange that the mindset of such petty Britishers should get utterly distorted? Gift a horse to a person that has never ridden one in his life —he will torture the beast with whiplashes – not knowing that a mere tug at the reins is enough to control the beast. But at times you will find a civil Britisher who could stay untainted even after being surrounded by the contagion of Anglo-Indianism —who has not become proud and arrogant even when bestowed with unhindered authority and power. To stay unblemished in spite of being away in India, far from one’s own societal circle, and surrounded by thousands of servants, is a veritable trial by fire for the gentle and refined mind.

Anyway, the ship reaches Southampton at last, bringing our Bengali passengers ashore in England. The next destination is London. While deboarding, a British Guard comes and asks if they need any help. He helps them fetch the luggage and call for transport. They wonder “Oh! How well-behaved these English people are!” That the British could be so polite was beyond their imagination. True, one did have to tip the Guard with a shilling, but what is a trifling shilling to a newly arrived Bengali if he is honoured in return with a salute from an Englishman?

The people I spoke to have been staying too long in England to remember exactly how they felt on experiencing the various trifles for the first time. They could only recall those experiences that had a lasting impression on their minds. Before they arrived in England, their foreign friends had rooms fixed for them. On entering the rooms, they find a carpeted floor, frames on the wall, a large window on one side, sofas and chairs, a couple of glass vases, and a small piano. What a calamity! They call their friends and express their consternation, “Do you think we have come here to show off? We don’t have money to spend on such finery, we cannot afford to live in such rooms!” Their seasoned friends are greatly amused, for by then they had totally forgotten their own similar situations many years back. They take the newcomers as petty rice-bred Bengalis and comment with the smugness of a pedant, “Here, rooms look like this everywhere!”

To our newcomer these bring back the image of the home that he has left behind…A damp room with a cot and a mat spread on it, scattered gatherings of a hookah, a game of chess with friends with a scant piece of cloth knotted around his waist, a cow tied in the courtyard, the wall adorned with dung cakes, damp clothes spread on the verandah, so on and so forth.

Their friends recall how acutely embarrassed they used to feel to sit on the couch, eat at the table, to tread on the carpet… lest these become dirty. They used to sit on the sofas quite ill at ease, lest the sofa got damaged. Surely the furniture was meant only for decorating the room, it could never be the landlord’s intention to allow these to be actually used and get spoiled.

Such is the initial reaction on seeing these rooms.

Now, let me talk of another major issue.

In the smaller houses in England, there perhaps exist a species called the “Land Lord”, but those who stay at these houses, have all their transactions with the “Land Lady”. Paying the rent, making arrangements for food and other requirements, all these are matters managed by the landlady. Upon setting foot for the first time, when my friends found an English lady welcoming them with utter politeness, they got flustered, and stood stiffly after managing to muster some suitable polite pleasantries.

But their amazement knew no bounds when they saw their seasoned Ingo-Bongo friends talk freely with the lady. Imagine their wonder of being in the presence of an actual “Bibi Sahiba” in shoes, hat, and gown!

The newcomers then start to feel a huge respect for their Ingo-Bongo friends. It was beyond their imagination that they themselves would ever gather the nerve like the seasoned ones. Anyway, after settling the newcomers in their respective quarters, the Ingo-Bongo-s go home and spend the week heartily ridiculing their friends’ ignorance. Our aforementioned landlady daily ask the newcomers of their requirements with utmost politeness. This used to afford great satisfaction to the newcomers. One of them reported of the immense pleasure he felt on the day he had actually managed to scold this Englishwoman! Wonder of wonders. That day, too, the sun had not risen in the West, mountains did not wander around, and the fire too, had not turned cold.

Thus, they start living in great comfort in their carpeted quarters. As they say, “Back home, we had no room we could call our own; the room we sat in would be used like a thoroughfare. I would be writing sitting on one side, my elder brother dozing, book in hand, beside me. On my other side, the tutor would be loudly teaching the tables to young Bhulu. Here, I have my own room; I can arrange my books and writing tools according to my own sweet will. I would not have to live in constant dread of some boys coming and upsetting the arrangement, or coming back from College to discover two or three books missing, and after a frantic search, finding my young niece looking at its pictures with her tiny companions. Here, you can sit in your own room with the door closed, with no one to barge in without notice, people would knock at the door before entering, no hullabaloo or shrieking of children around, it is all quiet and cosy with no troubles.”

Our newcomer, then, becomes quite vexed with his native land. You will often find that gentlemen from our country are reluctant to interact with the menfolk here. The reason is that you need a kind of hearty spiritedness to mix with men here, you cannot take the shortcut of uttering a few yes’s or no’s with polite diffidence. But, our Guest the Bengali is adept at gently whispering a few sweet nothings in the ears of his fair companion at the dinner table. The heavenly bliss he feels in the company of the lady radiates from the tip of his head to the toe of his shoes, so that the Bengali gentleman has no problems in getting along in the female society. Stepping out of the dim inner wing back home and coming to the moonlit brilliance of unstinted beauty transports our Bengali psyche to sheer ecstasy.

One day, our Bengali newcomer attends his first Dinner invitation. Foreigners are highly favoured in such Dinner gatherings. He escorts Miss “___”, the young daughter of the landlord to the table. In our native country, we do not get to mix freely with womenfolk. Besides, coming to this foreign land, we cannot fathom the attitude of the ladies here, and often misunderstand the pleasantries and witticisms that they exchange with us merely out of social courtesy, as signs of special fondness for us.

Our Bengali youth regales Miss “___” with many tales relating to India, affirming his abiding fondness for England. He is most unwilling to go back to India, a land full of superstitions. He even ends up telling a few white lies, such as having narrowly escaped death while hunting a tiger back in the Sundarbans. Miss “____” easily gathers that this youth has been smitten by her. The thought pleases her and she, too, begins to shoot arrows of the sweetest utterances.

“Ah… What clarity of expression! Where were those painstakingly awkward one or two ‘yeses or ‘no’-s that seemed to disappear where they erupted– behind the veils and where is this abundance of honeyed verbiage flowing unrestricted, without waiting for invitation from the luscious lips into one’s veins!”

Now perhaps you can understand what kind of spices go into the making of the concoction called the Ingo-Bongo from the original Bengali. I have not attempted to elaborate here the whole process. This letter would become enormous were I to discuss the details of all the factors that wreak such sea-change in the human psyche.

To better understand the Ingo-Bongos, you have to observe them in three situations, namely, their behaviour in front of the true English, with Bengalis, and with their own clan, that is, the Ingo-Bongo. Observe the Ingo-Bongo in front of an Englishman, your eyes will be gladdened. The head keeps bowing down in excessive politeness at every word, the tone excessively cautious even in argument, utterly apologetic when protesting, and begging a thousand pardons for having dared to differ. Even if he doesn’t speak and sits quietly near an Englishman, his every word and gesture exudes the utmost humility. But lo and behold the temper of our Ingo-Bongo when he is amidst his own circle. The person who has stayed in England for three years considers himself unattainably superior to the one who has been there only for a year. And you get to see the might of the “three-years” if ever a “one-year” dares argue with him. He speaks every word with such certainty as if it is Divine Oracle. To him, the one who dares protest is a benighted fool. The other day, a friend of ours was describing a Bengali gentleman who asked him, “What is your occupation, Sir?” Instantly, an Ingo-Bongo friend uttered in sheer disgust “Just see, how barbarous!” The logic being that just as not telling a lie, or not to steal, are moral edicts, so is refraining from asking a person his occupation. One day, we fell into talking of the traditional Bengali Hindu shraddha, and our custom of taking havishyanna (purified food) after the death of a parent, or not engaging in grooming. An Ingo-Bongo youth turned to me with great impatience, “Surely, Sir, you do not think these customs as proper?” I said, “Why not? As far as I can gather, if the English were to consume havishyanna after a relative’s death, and we natives did not do so, you would have detested your fellow natives and thought that not having havishyanna was the principal reason our country was in such bad shape”.

You may be knowing perhaps that the English consider it unlucky to have thirteen people dine together at a table. They believe that one of the thirteen would surely die within a year. An Ingo-Bongo, while inviting people for dinner never ever invites thirteen guests. If asked, he says “Well, I myself do not believe in such superstitions, but I have to obey the custom lest my guests are disturbed.” The other day, an Ingo-Bongo gentleman was forbidding his nephew from playing in the streets. The reason? “What would people on the street think?”! Some Bengalies say they want to start the English custom of rented rooms in their native country too. This is the height of their ambition. Yet another Bengali youth wants to reform Bengali Society. To him, the English custom of ladies and gentlemen dancing together seems the most perfect of social practices. Having found the common features that distinguish English ladies from their counterparts back home, our Ingo-Bongo starts finding fault with specific issues. For instance, the desi women do not know how to play the piano; they don’t know the etiquette of entertaining visitors or paying visits themselves. As they go on finding fault with every trifling difference between their native county and England, their annoyance keeps mounting on a meter. One Ingo-Bongo remarked that he no longer wants to return home whenever he thinks of the native women who would surround him and start wailing in monotone. That is, what he wants is a wife who would embrace and kiss him, call him “Dear” and “Darling” and lay her head on his shoulder. You would be amazed at the degree of their research on how the fork and the knife should be held “just so” at the dinner table. They are the epitome of expertise on matters like which cut of the coat is fashionable, whether the nobility wears their trousers loose or tight, whether they dance the Waltz or Polka Majorca, or whether they take meat before fish or the converse. The fuss the Bengali makes over such trivia are unmatched by the real English. An Englishman does not mind if you eat fish with a knife, as he knows you to be a foreigner. The Ingo-Bongo, however, would need smelling salts.

Likewise, an Ingo-Bongo will gape at you in consternation should you drink champagne in a sherry glass, as if world peace has been ravaged because of your ignorance. He would, were he the Magistrate, have you exiled in solitary confinement if you dare to wear a morning coat in the evening. I know one abroad-returned gentleman who, on seeing someone taking rye with his meat, remarked, “Why, then, do you not walk on your head?”

Another fact that I find astonishing is how the Ingo-Bongo disparages their native culture in front of the English, to such an extent that not even an Indo-phobic Anglo-Indian would engage in. He deliberately raises the topic and proceeds to heartily ridicule the various Indian superstitions. He describes the Vaishnav community called the Vallabhacharyas in a comical way, and caricatures the way desi nautch girls dance, deriving great pleasure from the merriment of his spectators. His earnest wish is that nobody should take him to be an Indian. The greatest concern of the pseudo-English Bengali is lest he is exposed as a Bengali. A Bengali was once accosted in the street by another Indian gentleman who spoke to him in Hindustani. Our Bengali gentleman was highly incensed and left rudely without answering. His wish is that no one should take him to be a Hindustani-speaking Native.

An Ingo-Bongo has composed a “national anthem” to be sung in Ramprosadi style. I have already written a portion of it in my earlier letter and am trying to reproduce the rest here as I remember. Rather than a devotee of Shyama, the Goddess of Darkness, the author of this song is a worshipper of Gauri, the fair one. And thus he prays,

O Mother, I shall be reborn as a “Sahib” when I die,

I will put on a hat on my red hair and erase the label of a bloody “Native”

I will hold a fair hand and wander in the garden,

And I will look away in scorn should I chance on a dark face.

I have already mentioned the landladies in Britain. They serve the tenants as and when necessary, engaging maids to help around if the number of tenants become large. Sometimes, their relatives also stay in the house to help around. There are some gentlemen who look for good-looking landladies when hiring a house. Their very first step in entering the house is to become familiar with the landlady’s young daughter, who is then anointed with a new pet name and an ode penned to her before the week is out. The other day, the landlady’s daughter asked whether the gentleman needed sugar with a cup of tea she had brought him. Our hero smiled and said, “No, Nellie! I don’t need sugar now that you have touched it!”

I also know of another Ingo-Bongo who called his household helps as “MejDidi”, “SejDidi” and so on. One gentleman known to me used to revere his coterie of MejDidi-SejDidis so much that if his friends engaged in some pleasantries while one of them happened to be present at his room or an adjacent room, he would get excessively worked up and say, “Hush! What would Miss Emily think?” I remember while in India we invited a gentleman who had returned from abroad. At the dinner table he sighed and remarked, “This is the first time that I am dining with no ladies present at the table!” Once an Ingo-Bongo had invited some of his friends. A group of landladies and maids were sitting at the dining table, one of whom was wearing clothes that were not too clean. When the host asked the lady to change into clean clothes, her response was, “If you love a person, you can love her even when her clothes are dirty!”

And now, let me tell you about another of the virtues of the Ingo-Bongos. Many among those who come here do not admit that they are married, as the married are not much in demand in the social circle of young unwed women. If you announce yourself as a bachelor, you can get away with many misdemeanors with the ladies, but if your friends come to know that you are married, they would not allow you to engage in such transgressions.

You will come across many Ingo-Bongos who do not fit this description. But I am merely pointing out the common characteristics of the usual Ingo-Bongos as far as my knowledge goes.

I have little experience on, and little to say about, how our Ingo-Bongos fare when they go to India. But I have some experience to share about those who return to England after having spent some time in India. They no longer find England as attractive as before; and often wonder whether it is England that has changed, or they themselves. Earlier, they used to be charmed by even the merest trifles in England, but now they no longer like the English rainy season, or the English winter. Now they are no longer sorry to go back to India. They say that earlier, of all the fruits they have eaten, the English strawberry used to strike them as the tastiest. But, has the taste of strawberries themselves changed in these few years? Now they find desi fruits much tastier. Earlier, they used to adore Devonshire Cream, but now they find the desi “kheer” much superior. They return to India and start living the domesticated life with their wife and children, earning their livelihood. Gradually, their roots become entrenched in India. Their minds become sluggish, and all they wish for is to sit back and enjoy the soothing breeze of the pankha. Even if all you want in England is to enjoy recreation, you need to put in quite a lot of effort. Here you cannot afford the luxury of coaches to move from here to there, or a bevy of servants waiting on your hand and foot. Cab fares are excessive, and so are the wages of servants. If you wish to go to the theatre, you will have to endure the evening rain and mud on the streets. You have to scamper over miles, umbrella in hand, before you can reach there on time. All this you can do only when you have young blood flowing in your veins, not otherwise.

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

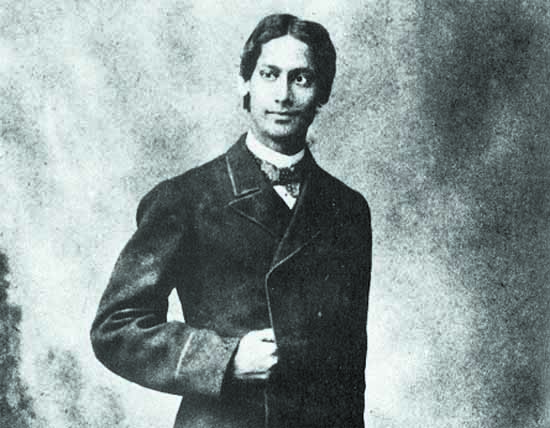

On the later recollection of this first voyage of a seventeen-year-old youth, Tagore regarded his state of mind as one where the fertile land of his personality was replete with thorns—prone to poke at everything that came his way. He felt the correspondences penned during this phase as expressing more audacity, expecting kudos from his readers, rather than something more substantive. To a mature Tagore, on reflection, his own attitude during this time appeared as if to boast of one’s individuality or superiority over the run-of-the-mill average visitor. Looking back at his attitude during this time, the wise poet observed it to be dominated by an urge to set one’s superior individuality apart from the so-called mediocre visitors. Hence, upon retrospection, Tagore deemed the letters disrespectful toward the countries he had visited. Also for the poet, his younger self who composed the letters seemed naive in his perspective of the world. And so, he never agreed to have these letters published In spite of all their flaws, however, one justification that Tagore believed, could be offered in favor of Europe Probasir Potro is its language. It was probably the first prose matter in Bengali literature written in the colloquial tongue.

To read earlier episodes of the series on Memoirs & Letters: Tagore in Translation, visit the following pages of The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments