It would be futile to list out the many rewards this book has for its name. A book published back in 2007 has already seen the thick and thin of appreciation and criticism.

It is no surprise that every bit of life is a story and the difference between an author of might and her/his readers is that they can conjure one from another. When we read them all, we find a strange connection between the two where feelings suddenly start running up and down the edge of what we call empathy.

Any pentagenerian reader must have come across many travelogues in their lifetime. But moving through Flights is an experience unlike any, a journey in the practice of reading that reveals a perspective of life with an unmistakable undertone of crude yet textured dark neo-realism with the poignancy of simple, deep macabre. But this feeling never overrides life and its triumphant austerity over abstraction and its millions of possible courses. Every human life has to pass through this, over centuries. I think Tokarczuk has chosen the backdrop as the sliver of life between the 17th and the 21st century just to communicate such an eternity. This fragment of time is just a sample, a cognizable human history that the present day limits to its past for reference.

We are seeing it all through the eyes of a lady. Is she living for three hundred years to tell us her feelings? That’s for the reader to ponder. What Tokarczuk probably intended was to reveal the kind of those ladies with deep sensibilities, grappling with the eternal crisis to be understood. They probably never claim recognition. Just a silent cry for being placed and treated properly so that the darkness around them does not seem to dissolve into their skins through the pores:

…there’s nothing left to breathe. Now the dark soaks into skin.

Post these lines, words might seem scanty. And since this is no poem, she has to complete the journey she has started. Thus, despite creating such an aura with the opening, she moves on to the next lap, to a different journey, as a marvelous word-trotter.

In fact, the starting fragment: Here I Am somewhat summarizes her message. This fragment provides the very impetus to the rest of the movements in the rest of the fragments that create a magical conjuring where the fine line between life and death, happiness and suffering, ego and alter ego, is provocatively marred into a smudged silence of inevitable continuation of life entailed by death.

Darkness spreads softly from the sky, settling on everything like black dew. The worst part is the stillness, visible, dense— a chilly dusk and the sodium-vapor lamps’ frail light already mired in darkness just a few feet from its source. Nothing happens— the march of darkness halts at the door to the house, and all the clamor of fading falls silent, makes a thick skin like on hot milk cooling. The contours of the buildings against the backdrop of the sky stretch out into infinity, slowly lose their sharp angles, corners, edges. The dimming light takes the air with it— there’s nothing left to breathe. Now the dark soaks into skin. Sounds have curled up inside themselves, withdrawn their snail’s eyes; the orchestra of the world has departed, vanishing into the park.

Towards the middle of the book, in the fragment The Achilles Tendon, the echo of the somber reasserts its existence:

The host blows out the candle and disappears, then says out of the darkness: “We must research our pain.” (Page 194-195)

At times, the lucid and candid way of description shocks us with queer awe, making us want to exclaim: “Could this ever be described through words!”

Probing deeper into the technical terms used to explain and compare this to many other homogenous novels of reflection on recollections and establishing one linear mood of perception is not a fairway to transcend the queer feeling of reading this novel. We have seen the media and the exhaustion of their best vocabulary in appreciation of the novel. This one-of-a-kind ‘fragmented novel’ that the world has ever seen has now left the readers with a lack of words to describe the feeling of reading it. It feels like there is nothing left to be said about this novel, and here in the write-up, appreciation completes the second page in its admiration.

Tokarczuk is a humanist. Her linear salvage to humanism here is quite outstanding. The mingling of ethics, knowledge, and values of life are more modernist where the individual narrator is either too big or too small when contrasted with its complementary society. The presentation of mundane experience is so vast and significant that it never gives the reader the feeling that the society and the individual are running either ever parallel, never meeting one another, or hand in hand. In fact, they are running complementary to one another— be they parallel or intersecting each other. That is what is happening all through— one supersedes the other and then again flips their position. Even in her treatment, the humanistic concerns never come to the surface, flowing only underneath as it compels one to wonder time and again: Why has the narrative been written over the three centuries of perspectives of “a” woman? Why?

Sometimes the author or the poet never knows about something which the critic has creamed off its beating. William Shakespeare never wrote those plays with the objective to create eternal literature. He just wanted to be rich as a producer and thus turned out to be one of the world’s unsurpassed script-writers. He wanted his plays to sell in public. So he wrote what served his purpose the best. Similarly, Tokarczuk never thought that her narrative shall become a pivotal point, making her stand out on the global map as a staunch feminist, branching off from the greater concept of humanism.

The chiasmatic and non-invasive treatment of binding the parts to a whole and splitting the whole into parts with utter stoicism is a striking characteristic of this book. In her inadvertent and unattached style of storytelling, her ironic and chiasmatic dissociation with the self of the speaker or the narrator is evident. In the chapter Travel Tales, she describes it as:

As it is I’m taking on the role of midwife of the tender of a garden whose only merit is at best sowing seeds and later to fight tediously against weeds. Tales have a kind of inherent inertia that is never possible to fully control. They require people like me— insecure, indecisive, easily led astray. Naive. (Page No: 219)

Anna Aslanyan, in The Spectator, has aptly pointed out, “Trained as a psychologist, Tokarczuk is interested in what connects the human soul and body. It is a leitmotif that, despite the apparent lack of a single plot, tightly weaves the text’s different strands— of fiction, memoir, and essay— into a whole.”

The unique cadence of the book is gripping, too.

“The book’s prose is a lucid medium in which narrative crystals grow to an ideal size, independent structures not disturbing the balance of the whole.” — Adams Mars-Jones in London Review of Books

This striking balancing of the whole to its part and the parts to a whole has different possible intonations through varied wits of the learned critics. The translation of the original Bieguni in Polish to Flights in English is no easy task. Jenifer Croft did not share fifty thousand pounds of the Booker Prize in 2018 with Tokarczuk just as a courtesy. The might of the literary panache in Croft did it all because according to Adams Mars-Jones: “….she (Jeniffer Croft) can give the impression, not of passing on meanings long after the event, but of being the present at the moment when language reached out to thought.” This is not just a sense translation. We can see every bit of imagination in Tokarczuk to get a perfect sync to what Croft has understood and flawlessly represented. In her way of representing the mind of the native Polish lady speaker, there remains no white space between the conception of the primary author and the impeccable understanding of the same while translating it into a different language. There remains no gap, absolutely. The reader finds no loss of ethnicity through translation. Adams concludes beautifully that: “The cascades of concise interstitial passages are often satisfying riffs on time and space, bodies and language, repetition and uniqueness.”

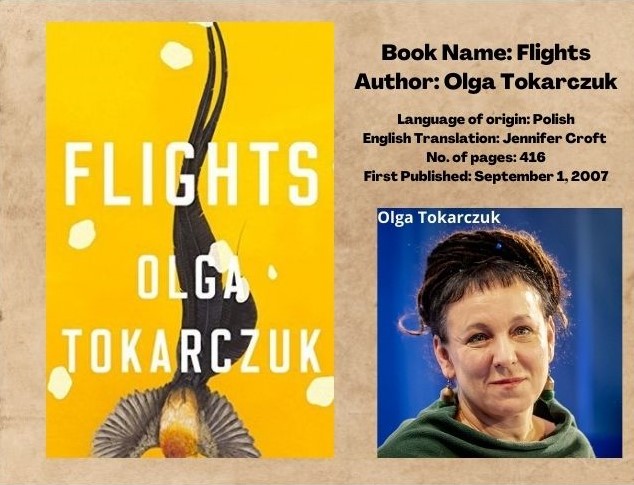

Jennifer Croft, the translator of Flights

The root of the novel with the original name Bieguni refers to the runners of once-upon-a-time Poland. The Bieguni used to be a section of people who believed that “being in constant motion is a trick to avoid ‘evil’ in archaic Poland.” So run and run and run— run for life and existence. No evil is going to touch you.

However, such a quest of running for eternity to avoid evil is going to bring in an inevitable rootlessness with acute ruthlessness.

“This is a book about rootlessness in the grandest sense— which is to say it is a book about mortality.” — Amanda De Marco in Times Literary Supplement.

The basic theme of constantly being in motion to avoid evil is an irony of fate. In turn, it invites danger, the extreme danger, and ensures that the mortal fate is preponed. This is not healthy. A man’s craving for a constant voyage is just a dream. One may take a break from the static, mundane life, and find fuel for energy with temporary mobility. Constant mobility is exasperating. Olga Tukarczuk does not glorify this mobility. With a blind belief in mobility, human beings move on, though they hardly want to, and thus fall victim to the vicious ushering of the morbid death somehow. The constant conflict between a very poignant life trying to run with the facade of happiness and the inevitable direction of it towards death cook a palatable dish of “passionate and enchantingly discursive plea for meaningful connectedness, for the acceptance of ‘fluidity, mobility, illusoriness'”. DeMarco’s intensive sense could thus feel the real pulse of this intended fragmentary novel: “An ambitious work about travel (broadly conceived) that intermingles fact and fiction and takes theme, not narrative, as its guiding star. For those with a taste for chaos, there are many rewards.”

What is believed is that every great work of art must have a universal appeal. A book getting rewarded thus does not make it more classified for readers with finer sense and intellect. On the refreshment or entertainment value of this book, I really owe my courtesy to Eileen Battersby, Los Angeles Review of Books, as she checks on the basic elements lurking within the book with fantastic bravura entry strewn with literary ideas which are to be incorporated as the art of writing in future: “A select few novels possess the wonder of music, and this is one of them. No two readers will experience it exactly the same way. Flights is an international, mercurial, and always generous book, to be endlessly revisited. Like a glorious, charmingly impertinent travel companion, it reflects, challenges, and rewards.”

The music is not only the words but the large symphony every note in it creates… a correlation of making fragments into whole and splitting it up into fragments again, both having their vitality in connecting the world and the smallest bit of life in it.

The simplicity in the music is so gripping that “Hotels on the continent would do well to have a copy on the bedside table. I can think of no better travel companion in these turbulent, fanatical times.” — Kapka Cassabova in The Guardian.

In this age, what matters is getting connected to as man, to the whole… and so this novel serves the purpose well.

“A delicate, ingenious book that is constantly making new connections.” — Justin Jordan in The Guardian

…And two different readers are never going to feel the same way.

Also, read a book review of Incandescence written by Mehreen Ahmed, published in The Antonym.

Radiating the Incandescence: Reading Ahmed & Remembering Tagore

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and interesting updates.

For the month of September, The Antonym will be celebrating Translation Month to mark International Translation Day celebrated on 30th September. A number of competitions, giveaways, podcasts, and more have been lined up for the occasion. Please join The Antonym Global Translators’ Community for updates!

0 Comments