A BOOK REVIEW BY OUDARJYA PRAMANIK

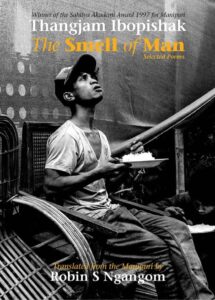

“The Smell of Man – Selected Poems” is an extraordinary anthology that introduces English-speaking readers to the mesmerising world of Manipuri poetry through the lens of Thangjam Ibopishak. This collection of 47 poems, masterfully translated by Ngangom, transcends linguistic barriers to delve into the complex tapestry of Manipuri life. Ibopishak’s evocative verses navigate the intricate dynamics of a region marked by violence, conflict, and social upheaval. In this review, we journey through a few poems, examining their themes, metaphors, and socio-political undercurrents, ultimately revealing the profound impact of Ibopishak’s work.

North East India has long been marred by conflict, violence, and corruption. The introduction to this collection highlights the historical context of Manipur and its struggle for autonomy, set against the backdrop of stringent governmental measures like NSA, TADA, AFSPA, and UAPA. These measures have created a volatile and sensitive region, where daily conflict and corruption prevail. Thangjam Ibopishak and other regional poets engage in what can be termed “Poetry in a Time of Terror.” Their verses serve as a poignant reflection of the grim realities they face, using poetry as a tool for resistance and expression.

To begin with the titular poem, “The Smell of Man,” is a tour de force that encapsulates the essence of Manipuri life amidst turmoil. Ibopishak employs sensory imagery to vividly depict the region’s complexities. The fragrance of old newspapers and garden blooms, juxtaposed with gatherings and protests symbolises Manipur’s history of voicing concerns amid conflict. The poem underscores the resilience of Manipuri people through metaphors like ants seeking sugar and a family’s daily struggles.

It delves into themes of longing and estrangement, possibly mirroring the emotional toll of residing in a conflict-ridden area. The contrast between nature’s beauty and the evening’s darkness emphasises the coexistence of both in Manipur’s landscape. However, the poem takes a dark turn, exploring the grim consequences of violence, exemplified by a woman selling the bodies of children killed by gunfire. It concludes on a haunting note, highlighting the desensitisation that can occur in the face of prolonged suffering, leaving readers with a sombre glimpse into life in Manipur.

Thangjam Ibopishak’s body of work, particularly in his later poems and prose poetry, takes on a starkly satirical and didactic tone, shifting away from pure aesthetic contemplation. Instead, he directs his creative energy towards critiquing societal injustices, corruption, and oppression, often leaning more towards a form of poetic propaganda. This transformation is reflected in his transition from traditional poetry to prose poetry and conversations in his later works.

“The Ghost and the Mask” delves into the internal struggle of individuals in Manipur, where conflict and turmoil have left indelible marks on society. The poem presents a symbolic demon representing the dark forces that can grip one’s conscience amid adversity and injustice. The protagonist grapples with the demon’s influence, symbolising the temptation to abandon morality in the face of suffering. However, it ultimately highlights the internal battle to maintain virtue and humanity despite external pressures. This mirrors the moral dilemmas faced by individuals living in Manipur, where conflict tests their humanity and resistance to cruelty’s allure.

Ibopishak’s exploration of dystopian themes within his poetry embodies what M. Booker describes as an “oppositional and critical energy.” His poems serve as a reflection of a dystopian impulse, mirroring a world where societal miscarriages of justice are deliberate and systemic, as defined by Erika Gottlied’s understanding of dystopian fiction. In this context, Ibopishak’s satirical verses serve a didactic purpose, acting as a sharp critique of societal injustices, both in prose and poetry, effectively challenging the conventional concept of justice.

In “Gandhi and Robot,” Ibopishak’s satire shines through as he provides a commentary on India’s historical and contemporary affairs. The poem juxtaposes technological achievements with the stark realities faced by common people. It offers various symbolic representations of Indian political leaders and their connection to cultural and societal values. Nehru’s robot chanting ‘Hare Ramas’ represents a fascination with technology, possibly signifying a disconnect from cultural values. Vallabhbhai Patel’s Gandhi spinning thread contrasts simplicity with the modern world, emphasizing the nation’s heritage. Vikram Sarabhai’s Trombay site reflects India’s emphasis on scientific progress. The donkeys braying at the Red Fort symbolize the struggles of the marginalized, suggesting detachment by leaders. Sadhus planning a pagoda at Pokhran may symbolize a yearning for spiritual renewal amid national challenges.

“My Diary” offers a personal reflection on inner conflicts, aspirations, and the discrepancy between ideals and reality. The poem explores individual identity, character, and the struggle between different aspects of the self. It emphasises the importance of honesty in confronting one’s cowardice and contemplates the defining qualities of humanity, character, and compassion. The metaphor of a mating season’s dog signifies a loss of control to base desires. The poem concludes with a sense of insignificance, possibly reflecting existential despair and disconnection from the world.

In his later works, one recurring and ominous theme is death, often accompanied by death threats due to his outspokenness. The prose poem “Die by India-made Bullet” stands as a poignant example. Here, Ibopishak portrays an armed group with formidable power and weaponry, intent on executing him for his writings. These group members, intriguingly named Fire, Water, Air, Earth, and Sky, possess the means to end his life, yet they refuse to employ India-made guns. The poet’s declaration of love for India ultimately becomes his lifeline, as he narrowly escapes death due to his preference for an India-made firearm. This episode serves as a stark reminder of the precarious position poets and writers find themselves in such contexts, where expressing their ideas freely could result in dire consequences.

“Mini India” is a vibrant portrayal of cultural diversity and harmony within a neighbourhood. It celebrates the coexistence of languages and cultures, challenging stereotypes with humour and symbolism. The poem symbolises the unity amidst diversity in India, emphasising the nation’s various communities living harmoniously together.

The poem “I Want to be Killed by an Indian Bullet” is a thought-provoking poem begins with the arrival of elemental forces, symbolizing nature’s fundamental aspects. It questions the protagonist’s identity and highlights foreign influence. The speaker’s love for India is evident, requesting an Indian-made bullet, which is refused. The poem underscores life’s unpredictability and absurdity, leaving the audience pondering the concept of identity, patriotism, and the irrationality of certain situations.

“Made in India” expresses deep love and attachment to India using metaphorical and humorous imagery. The poem highlights the willingness to bear burdens for the country’s sake, connecting the poet to India’s history and freedom struggle. It celebrates the nation’s heritage and values through clever metaphors.

The emotionally charged poem, “Me and My Mother” explores the complex relationship between the speaker and their mother. The poem employs metaphors and vivid imagery to depict the nuanced emotions and conflicts within the mother-child relationship. It ultimately hints at a changed perspective or understanding of the mother’s actions.

“Self-portrait” delves into themes of identity and self-perception, blurring the lines between reality and imagination. The poem’s surreal tone and introspective journey make it a compelling exploration of the self and the quest for understanding one’s own identity.

The poem “The Moon’s Face” unfolds against the backdrop of changing perceptions of the moon’s appearance over time. It uses the moon as a symbol to explore themes of nostalgia, love, and political disillusionment. Ibopishak skillfully navigates the passage of time and evolving perspectives, making the poem universally relatable.

“Grandmother” is a concise yet poignant reflection on aging and the enduring image of a grandmother. The poem employs a rhetorical question to emphasize the universality of the aging process, reminding readers of the inevitability of time’s passage.

“Eldest Son” contrasts the routine life of the eldest son with his approach to owning books. The poem critiques indifference to education and underscores the importance of active engagement in learning, highlighting that owning books alone is insufficient for true knowledge.

The beautiful poem, “Woman, Your Body is a Lovely Continent” celebrates the richness and complexity of a woman’s body through vivid metaphors and imagery. It elegantly portrays femininity’s ever-changing nature and its enduring resilience.

“White Paper/Black Ink” is a playful yet profound exploration of the literary process, highlighting the roles and dynamics involved in creating and consuming written works.

“Three Songs” effectively captures the essence of each of the three songs, highlighting their themes and the poet’s contemplative approach to life, memory, and human experiences. The poem provides a clear understanding of the depth and complexity of the songs.

Ibopishak’s poetry is a stark and unfiltered lens through which he shines a light on issues that are often overshadowed or suppressed due to fear and oppression. His verses do not provide solace or easy solutions; instead, they confront the world’s flaws head-on, emphasising a sense of hopelessness. His focus isn’t on the presence of justice but rather on its painful absence. Through his poetry, he captures a sense of entrapment and a lack of hope for emancipation. Ibopishak’s unapologetic portrayal of Manipuri society’s harsh realities, marked by cruelty, exploitation, and injustice, leaves no room for romanticizing life’s sublime moments or emotional beauty. Instead, his poetry acts as a potent form of social criticism, a protest against complacency, and a wake-up call that compels us to acknowledge and address the stark and corrupted world we inhabit.

Robin S. Ngangom’s introduction to Thangjam Ibopishak and Manipuri poetry contextualises the poet’s significance within the broader literary landscape. It highlights the transformation of Manipuri poetry after World War II and the emergence of a more introspective and satirical style. Ngangom’s dedication to bringing Manipuri poetry to a wider audience is commendable, and the acknowledgment of the limitations in translation underscores the ongoing process of bridging linguistic divides.

“The Smell of Man” is a tour de force of Manipuri poetry, offering readers a rich and multifaceted exploration of life in Manipur amidst turmoil. Thangjam Ibopishak’s verses resonate with timeless themes of humanity, identity, and societal challenges. Ngangom’s translation skillfully captures the essence of these poems, making them accessible to English-speaking audiences. This anthology stands as a testament to the power of poetry to convey the human experience and provoke thought, even in the most challenging of times. Ibopishak’s work serves as a bridge between cultures, fostering a deeper understanding of Manipuri life and literature.

In the spirit of Asutosh Mookerji’s vision of translating diverse Indian literature into Bengali, this collection of Thangjam Ibopishak’s poetry expands the horizons of literary exploration, enriching our understanding of Manipur and its poetic heritage. “The Smell of Man” is a must-read for anyone seeking profound insights into the human condition and the enduring power of poetry to transcend boundaries.

Also, read a Bengali fiction by Joya Mitra, translated into English by Kausambi Patra, and published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments