When restlessness is triggered by an internal glance at the self and the hours of stillness are transformed into long days of stillness through staring, a muscle twitches in the body. The muscle can be in the hands, arms, legs, or a sigh that stretches across the breast. Words, colors, patterns, floating steps and notes explode. Those who internally glance at themselves reach the secret of standing still where they are. The rest is the sweat of sadness, joy, love, passion and impudence, overflowing from the muscles triggered by the captivity of restlessness. Rejection surrounds them when they look out from where they are buried. They cover themselves with art as a shield for the battle against what they reject.

Translated from the Turkish by Gözde Zülal Solak

Walking vacantly from the Gare Montparnasse to Avenue du Maine, I grumbled. I looked for the streets I remembered from the letters he wrote to his friends. I was confused because the desolate streets resembled each other and the buildings were adjoined; I found myself in the same street I had walked fifteen minutes before. Whenever I hit the road, Paris resembled a mirror within a mirror, drowning me in deep thoughts, alienating me from myself and making me lose my way. I didn’t remember the name of the street I looked for. Internally gazing at myself, twice I became absent-minded. Ignoring the ache of my thighs because of excessive walking, I nearly hit the wall of a deserted desolate building in the street I was on after I passed the Boulevard Jean Moulin. It was a dead-end street; my heart beat with excitement. Could it be? I looked at the signboard: “Impasse du Rouet.” Deep internal glances unite the mad ones in the external world.

Impasse du Rouet

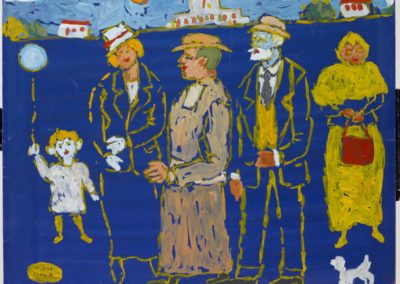

I came here to see you. I brought wine, cheese, baguette and some pickles. Your solitude haunted me. Thinking you would swear or dismiss me, I was afraid of climbing to the sixth floor of the apartment at the end of Impasse du Ruet. As I knocked on the door in silence, I had already decided to walk back in case you didn’t hear. But you opened the door, toothless and I saw the gap under your upper lip when you smiled. At that moment I realized you could neither swear nor say a bad word to me. I entered your devastated studio. It was your bedroom, atelier and kitchen all gathered within a room. Your old clothes were hung on the joist of the door, your painting materials were tidy and clean. The room smelled thinner, of paint, cigarettes and humans. But you wanted to live in a wide, big house, bright furniture, mahogany tables, and great libraries. Soap-scented linens, silver forks… A house resembling the house you were born in Moda. I felt you enjoyed isolation. Though you complained no one knocked on your door for months, you secretly enjoyed being safe and away from the police. They were all rascals, like you said. They were on your back from the Galatasaray Police Station, they chased you from Berlin, Paris. They chased you like a shadow. Never mind, show me some paintings. I will take what you show. In the purple painting, I felt I saw the little Fikret running at Kuşdili Meadow. You breathlessly hurled yourself, your uncle Hikmet Topuz (one of the founders of Fenerbahçe Sports Club) was your greatest hero. You enjoyed going to the football matches with him and encouraged yourself to be a great football player. Your mother insisted on naming you Mualla because she expected a girl, but they chose Fikret because you were a boy. In the photographs you smiled sweetly with your curly hair, you ran pulling down on your white dress. I saw you tripping, stumbling and falling in the backyard of Galatasaray High School, where you were enrolled to restrain your misbehavior. You stood up breathing out the soil from your nose. I saw your whole life at that moment. Rather than your broken, swollen leg, I looked at your life going astray. As you lay on the ground, time flew in and out of us. Could it be described as a fate transformed with a trip? Should we feel sorry for your lameness, which was the only reason for women keeping away from you and you keeping away from them, or should we feel happy your hands, which began twitching because of “too much internal glancing” after leaving the dreams of being a football player, turned to painting? It was a burden to know you lived your life being embarrassed of your lame leg with irrecoverable frustration, you looked at your loved ones saying “but they wouldn’t like me.” On top of that, you transmitted the Spanish flu to your mother, you recovered, but she passed away… You carried your basket full of guilt. Your bones became apparent on your shoulders, you became impudent and cruel. You didn’t forgive yourself. Because your father married someone again, you wreaked your anger by beating his young wife then leaving Istanbul. We followed the streets that many painters passed by in Impasse du Ruet. We saw the Eiffel Tower and the House of Balzac from below the Seine River and Saint Germain from above the cemetery. Our common point is the dead end where we made fools of ourselves trying to run lamely and we bumped into the same wall. Your hands drawing twenty paintings in one night in a rush and my hands writing twenty stories in one night in a rush met. It was the place where we took shelter, though we wanted to wander the boulevards. Impasse du Ruet was the name of the knotted thread we weaved through the complicated sentences, the swearing we uttered and the empty-handedness after we couldn’t find what we expected.

I Think of a Revolution in Painting

Leaving Sweden, where you were sent to study engineering, you went to Germany and confidently studied painting, which brought you to your teacher Arthur Kampf. Your encounter with this man would affect you more traumatically than the change of your life with a simple trip during the football match. What could this man do to you when you chose your own way with your own style, ignoring the things he taught after returning from Germany? Though you missed your city being away from the War of Independence, you surrendered to the harmony of Futurism. Saying “I think of a revolution in painting.” You meant Turkey. So you returned. What a return! You were discharged from being an art teacher at Galatasaray High School, where you found a job thanks to your friends. Then you were discharged from being a teacher at a school in Ayvalık, which was a job you hardly found… In the first case, you were a mad man without a penny who ate too much at a restaurant, then when they wanted you to pay, you took off your topcoat, your watch and all your clothes up to your underwear. In the latter case, you were a fighter tired of the insults while leaving Ayvalık with a letter talking about the ridiculousness of painting at a place without electricity. You returned to Istanbul. You went to the Degustasyon Restaurant where you drank too much. You noticed the portrait of Ataturk on the wall, it was reproduced and spread everywhere (it would spread to school books later on). For you, it had a medium quality: Ataturk was not represented as needed. The owner of the portrait was your teacher, Arthur Kampf. You began swearing at him, cursing him, exuberating as you drank. Thinking you were swearing off Ataturk, Ekrem Muhittin Yeğen (who was the cook of Mustafa Kemal back then), sitting a few tables beyond, immediately denounced you. The police took you, you were beaten and your feet were whipped at Galatasaray Police Station. Then you were institutionalized in Bakırköy Psychiatric Hospital for eight months. When you left the hospital, you were the greatest vagabond with trembling hands and twitching eyes. You were penniless, handsome and cowardly. You followed the path of Lautrec. You had a way opening to Paris and shabby taverns. Fikret Adil, Avni Arbaş, Abidin Dino, Edip Hakkı… Your friends were with you when you prepared thirty paintings for the New York World’s Fair and received payment. They stood in wonder of you when you left as if you were escaping.

Away from Leblebistan

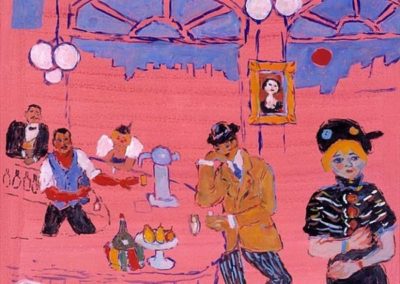

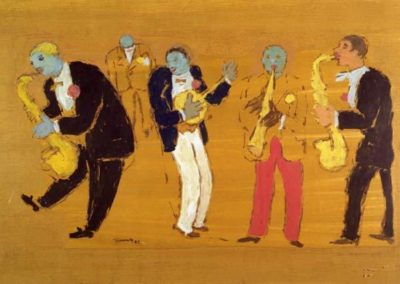

Modigliani, Utrillo, Lautrec, Van Gogh… Though they had common grounds, he was different from them (Mualla’s brush would mostly resemble Van Gogh’s brush). Bars, prostitutes, sexual incapacities, physical obstacles, poverty and alcoholism… Montparnasse was the neighborhood of the painters who gave the middle finger to life passing in eternal drunkenness and turned their backs to the bars like boomerangs after being dismissed. It was filled with streets intersecting the Boulevard Raspail and the Boulevard du Montparnasse. The art world of Paris grouped at the intersection of these two boulevards; especially the street of Grande Chaumiére, which was popular among the artists trying to find their way. The stores selling painting equipment, La Rotonde, Le Dôme (Mualla rarely visited Le Dôme because the prices were expensive), La Coupole coffees, sculptors, painters, strange women, mad men and Wadja Restaurant! Even if life stopped, colors wouldn’t stop there, the mind would be filled with various patterns and words. The street charmed the untalented, feckless to embrace the paper, pen and paint. It was perhaps the reason Modigliani went to Wadja so often. There you were! Away from “Leblebistan,” which was the place “the foul beaters” gathered, you made paintings for the price of a glass of wine. “I do whatever they want,” you said. I knew you were hungry. “The other day one of my friends ordered two still life and one landscape paintings. I’m trying to do them now. I don’t claim I must do figurative or abstract paintings. I do all of them. I’m not related to the other painters and cults. I’ve regressed so much compared to my old paintings. I stand out if I advance. They are afraid of the ones who shine and they try to undermine them. So I always look back. ‘Surrender,’ they say. Nothing doing! They would undermine if I surrender. I neither surrender nor advance. I stand in the middle.” Weak, lame and cheap painter… Do you say so to yourself? Please don’t. I hear you saying, “I loved a German. She rejected me saying I was wise and smart, but I was ugly and lame. So, I devoted myself to drinking.” Who else, which loves? They told me you laughed at the ones who said, I love you but I cannot make love with you… Hale Asaf, Semiha Berksoy who was in love with Nazım, and beautiful French women. You were the embodiment of alcoholic delirium. You didn’t escape from yourself, you still don’t (you only escape from the police). “I love my freedom,” you said. “I find it in my humble silence. I know I do something wrong or I am occupied unless I feel the silence in my brain and the roots of my hair when I am painting as I’m praying. To escape the wrong occupation, I go and drink three or five glasses of raki. If it continues, I look for people to swipe and fight as drunk as a lord.” On some nights when you cut the canvases with a razor blade, which you collected to put money in your pocket and raki, bread and wine in your stomach. You got pissed off during the heavenly times and you left and cried swearing to yourself with the happiness of your misery. I was as cold as you are in the humid attic exposed to wind from both sides.

Le Monsieur Qui Vit Seul (The man who lives alone)

They might call it misfortune, but remembering your memory of Picasso while feeling cold in Impasse du Ruet was enough for me to say you were such a soulful man. All creatures you didn’t appreciate or care about, including yourself, would astonish everyone talking about you in the after days. I was sure you could sell the portrait of a woman Picasso gave you in return for the price of a week of drinking without thinking. After all, you sincerely and honestly wrote to Fikret Adil, “I am obsessed with a new dress and clean underwear nowadays. I thought of you. Can you send it as registered post? I consent even if they are old.” I suppose if you knew people would talk about your paintings, finding buyers for a price fifty times more than the low price you sold, your anger towards the janitor woman, the paranoia you felt for the police next door which caused you to break into his house and put a handful of poop on his table and your raid at the embassy where you forcibly sold your paintings during the years passed within the triangle of police stations, madness and Saint Anne Hospital (Camille Claudel was institutionalized in this hospital as well), you would do the same things in an exaggerated way. You looked for a way out of troubles in your friends by writing, “Do not forget to place three or five candles in Mahmut Baba Mausoleum in Kadıköy when you visit,” when you didn’t have teeth or money. This makes me distill the pleasure and lament I felt in paintings. As I am about to be happy that you were saved and brought away from Paris (especially from the dead end) to a village where you worked for your patronage Madame Angles, I remember the orphans’ asylum where you died alone. I feel you saying, “Anyway, I died as I wanted to.” Yes, you did. In the night, during sleep. They easily got used to see you in Reillane where you found drinks by wandering the taverns, which Madame Angles forbade, you swore and created trouble. They called you “Le monsieur qui vit seul” – the man who lives alone. There was a song you sang before going to sleep on 19th July 1967, before dying. If I hear that song now, from your toothless mouth, can I fly from Impasse du Rouet to my home?

Notes

Impasse du Ruet – French. This is name of the street where Fikret Mualla lived in Paris.

Away from Leblebistan – Fikret Mualla was opposed to the Turkish government at his time, He used to refer Turkey as “Leblebistan” ironically, signifying a non-democratic country.

Author’s Note

Author’s Note

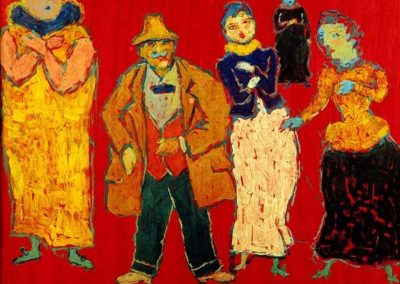

Fikret Muallâ (1904-1967) was a 20th-century avant-garde painter of Turkish descent. Though Mualla is thought to be “not understood” during his time, the reason for this is expressed by the artist’s unwillingness towards the mainstream social codes of his time. Spending 26 years of his life in France, the artistic style of Fikret Mualla gains inspiration from Expressionism and Fauvism, with his subject matter focusing on Paris street life, social gatherings such as cafés and circuses. Focusing on the bohemian inner world which makes Mualla different from the contemporaries and the last days of him, I wanted to open a window to the eccentric style of his artistic personality. I tell the days I have spent with him in this historical prose for the ones who have not met his art yet.

Author’s Note

Author’s Note

0 Comments