REVIEWED BY YASHODHARA GUPTA

“But because stereotypes have greater reach and penetration than ground reality, not many are able to shake Urdu loose from the escapist fantasy of popular perception; the few who manage to do so see Urdu for what it is: a real, living, tensile language forever willing to adapt, to replenish and renew itself”

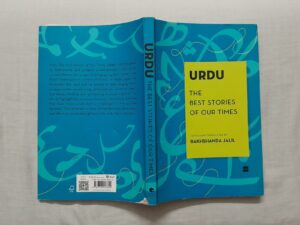

Rakhshanda Jalil in the introduction to her book Urdu: The Best Stories of Our Times talks of how she hopes this volume will, first and foremost, destigmatize Urdu as a linguistic system. She hopes to free the language from the binds of presumption and limitation, to translate to readers of the English language, the Urdu literary glory that lies beyond banalities such as ‘ishq-mohabbat’ or aesthetic romanticism. She hopes to bring us Urdu stories at their most primal attempts to capture human strife, to prove that the language can sing of rot and glory all at once, that these tales can hold on to love and grief and death and decay. She promises that these stories can live on.

And how they come alive, these stories!

Poor old Hori’s fertile fields and forsaken dreams greet us first, in ‘Scarecrow’. The landscape is painted skillfully by Surendra Prakash’s masterful writing, in golden crops, working songs, and a looming sense of stagnancy. A system of casual desperation is revealed as the old man, bereft of an heir, goes about preparing for the final harvest of his life. He works because he must. He hopes. He wonders aloud about what his years of labor have earned him. Prakash ponders what end there is, to a system exacting the very flesh and blood from this tormented farmer, while documenting the entire history of a land as she writes: “What a good time this is! There is no threat from the government functionary, nor fear of the moneylender. No tyranny of the British rulers, nor a share owing to the landlord!

The emptiness encased in the first story of the collection is mirrored in ‘The Halfway View’ and its forsaken violin cases. Love is lost, found, and settled for. Love is bought and traded, it is cruel and faithful all the same. Hyder finds a brimming pathos in two women who live completely different lives as they pine for a man who will belong to neither of them. Love and marriage exist separately, while choices are made in desperate hours for the sake of convenience.

The story maintains a distinct musicality in its contemplation of hope and leaves the reader helplessly searching for a what-if that is denied constantly by a harrowing narrative technique that makes use of familiar songs to further the grief in estrangement.

We are transported next to Khalid’s khatna ceremony and his anxieties about circumcision marking him as the target of vicious goons. The bloodied streams of Partition and communal violence slip into the mundane and personal, as Ghaznafar’s penmanship, sharp and precise, makes use of discomfort as a tool to ask us about the state of affairs through unfiltered questions that arise in a little boy. Anwar Qamar’s ‘What Happens on a Ship’, placed much later in the collection, takes up these very themes in a completely different approach. One can surmise, with some speculation, that the story has been placed in the aftermath of the 2002 Communal Pogrom in Gujarat. As helpless men and women are rendered homeless and forced to flee the lives they have known thus far, people begin to lose the very thing that makes them people- their souls.

The human heart is massacred by violence that claims piety, and these stories testify unwaveringly to this bloodied legacy carried on through human history.

Tariq Chhatari’s ‘The Line’ expresses a deep anguish resulting from the complete desecration of communal harmony. Switching between descriptions of the yellow-red sky and a Janmashtami-turned-massacre, the narrative details the reactionary violence born from conditioned hatred and mass hysteria.

The last story in the collection, ‘The Vultures of Doongerwadi’ posits death, symbolized by unmoving vultures who feast on corpses, as the end to futile struggles between disagreeing communities. These disagreements seem, to the living, the very summations of their being. The violence manages to convince humans that it is their final purpose. Despite all this, when death arrives, it does not choose. It does not ask the names of the bodies it consumes, or ponder about who was right, and who misspoke. The vultures move from corpse to corpse, and those who spent all their precious breath in spouting convictions of difference, end up all together in their stomachs.

Zakia Mushadi takes us to a remote village crippled by hunger, that has resorted to consuming rats to ward off the claws of hunger. A Dalit man from the Musahar community who has been promised eight rupees to march at a rally in a faraway city, remarks to himself- “Who knew what ‘inquilab’ meant? Puri-sabzi, sherbet, or simply a fat rat!”. The imagery of this overwhelmed man running in fright for his life in an all-consuming city, juxtaposed against his reputation as the expert chaser of many a rat, persists long after one has run out of pages to turn.

Gulzar’s ‘The Stone Age’ drags us to the ruins of a bomb-struck Afghanistan. Children die and families collapse. Homes become mere concepts, bloodshed the accepted day-to-day.

We, at present, live in a world marked by genocides, ethnic cleansing, and too many unequal wars. We find ourselves questioning our sheer helplessness and the meanings of modern civilization in the face of inhuman violence. This master storyteller finds his way into those questions, leaving us not with answers, but a treatise on the current state of geopolitics.

Khalid Jawed pens ‘A Letter of Condolence for the Living’ and narrates situations generally banished from the realm of the literary, in both form and image. The writing echoes the urgency required by the story, before taking a final dive into pensive contemplations regarding death.

Abdus Samad contemplates purpose and existence through his depiction of ‘The Halted Train’ cut off from modern amenities and stranded in the wild, while Syed Muhammad Ashraf in ‘The Last Exile’ crafts an unusual tale of ancient magic and the pursuit of divinity. Faiyaz Riffat brings in a completely different landscape in his depiction of a dehumanizing, cruel metropolis and the unfulfilled dreams that populate it. Salam Bin Razzaq takes up this very imagery of the decadent city, to comment on the troubles that plague economically stunted and socially ostracized, contemplating class, caste, gender, and religion. He discusses family planning and lack of space, describing the need for change and the complete absence of a chance at mobility. He comments on education, the rising rates of unemployment, and an inadvertent turn to religiosity in the face of social and economic damnation.

Jalil, in compiling, editing, and translating this volume, upholds the multiplicities enmeshed within the Urdu language. It emerges as a voice of resistance and dissent. It documents, through its many manifestations, the history of lands and peoples across time and space. The choices made in selecting the stories stand out splendidly, subverting the understanding of Urdu fiction being limited to Muslim communities. The fourteen short stories in this book contemplate life, death, class, caste, gender, and religion, and triumph ultimately in challenging all our ideas of what a story can be, how it can be told, and whether Urdu might be the tongue to spell it out.

Also, read Claiming The Sky, a book review by Oudarjya Pramanick, published in The Antonym:

Follow The Antonym’s Facebook page and Instagram account for more content and exciting updates.

0 Comments